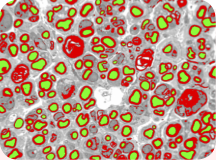

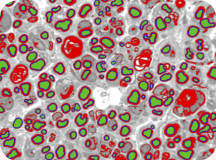

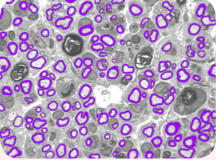

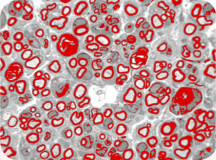

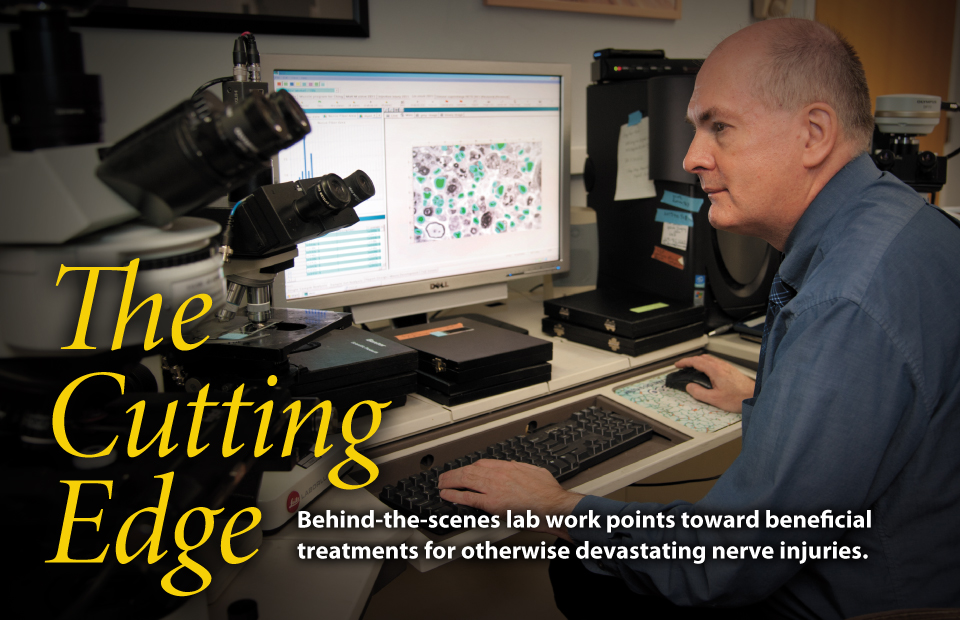

Imaging techniques developed by Dan Hunter and colleagues in the peripheral nerve lab set a standard for quantitative analysis of regeneration. Hunter modified computer software to augment the painstaking application of his lifetime of research experience.

Photo by Robert Boston

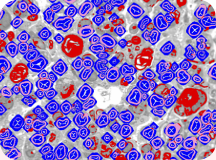

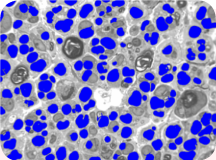

Microscopic nerve images are progressively refined and painstakingly labeled to yield valuable data on nerve regeneration studies.

BY JULIA EVANGELOU STRAIT

THE PAST 30 YEARS has seen a revolution in the treatment of injuries to peripheral nerves. Arms and legs, hands and feet rely on peripheral nerves to function and feel, and a few surgical specialists across the country have devoted their careers to fixing these delicate white fibers when they are damaged or broken. And behind the scenes, informing all of this surgical work, is the laboratory.

“Every question that comes up in the clinic, we have looked at in the laboratory,” says Susan E. Mackinnon, MD, the Shoenberg Professor and chief of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. “We bring the answers we discover in the lab back to the clinic and the operating room.”

Over three decades, this flow of information between laboratory, clinic and OR has led to huge shifts in the understanding of nerve injury and regeneration. Limbs that might once have been amputated can be saved: A patient’s own healthy nerves can be rerouted into a damaged limb, and nerves from a cadaver can be transplanted while minimizing risk of rejection.

A major figure in this work is Daniel A. Hunter, senior scientist in Mackinnon’s lab and an expert in the microscopic analysis of nerves. Mackinnon calls Hunter’s work an integral part of her surgical practice.

“Dan has devoted his life to quantifying nerve regeneration and developed his own unique techniques to measure what we see under the microscope,” Mackinnon says. “He can make the visual images of nerves — and they’re beautiful images — into actual numerical results. So you can compare different strategies for treating nerve injury in a very scientific way.”

Baptism by fire

On Hunter’s first day working for Alan Hudson, MB ChB, who later became neurosurgeon-in-chief at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, the windowless basement lab had a rotary telephone, a typewriter, an old surgical microscope, and an ultramicrotome, a device used to slice impossibly thin sections of biological samples to look at under microscopes. It was 1973.

“Dr. Hudson handed me a box of rat nerves,” Hunter recalls. “I asked what I should do with it, and he said, ‘You figure it out; I’m going on vacation.’ And he left. That was like baptism by fire. I think it was a test to see what I could do.”

In 1978, as a plastic surgery resident at the University of Toronto with an interest in nerve injury, Mackinnon sought out the Hudson lab. There, she and Hunter used animal models to do the first studies of immune response and rejection in transplanted nerve, paving the way for the first human nerve transplant, performed by Mackinnon in 1988.

Today at Washington University, 38 years after his first days in the lab, Hunter still works in a windowless room. Rotary phones and typewriters have made way for computers and cell phones. But the ultramicrotome, transplanted from Toronto, remains.

Since this particular ultramicrotome is no longer manufactured, Hunter does any required maintenance himself. Perhaps reminiscent of the transplanted nerves he examines, he harvests replacement parts from his stash of secondhand ultramicrotomes of the same make and model.

Peripheral

visions

The peripheral nervous system sends neural impulses to and from the brain, directing the body as it interacts with its environment. Click on a dot to see a microscopic view.

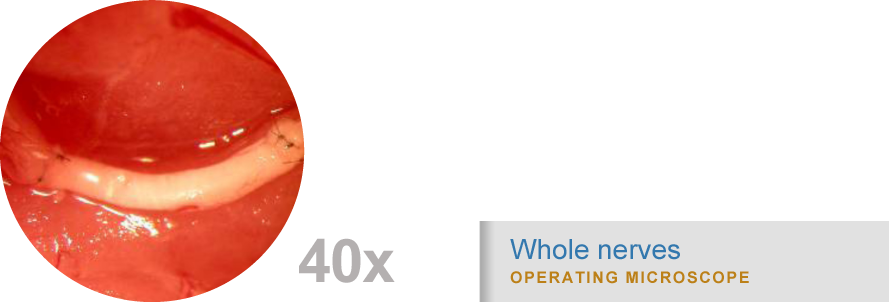

Surgeries use nerve regeneration techniques first verified by imaging studies in the peripheral nerve lab.

“Old school,” new tricks

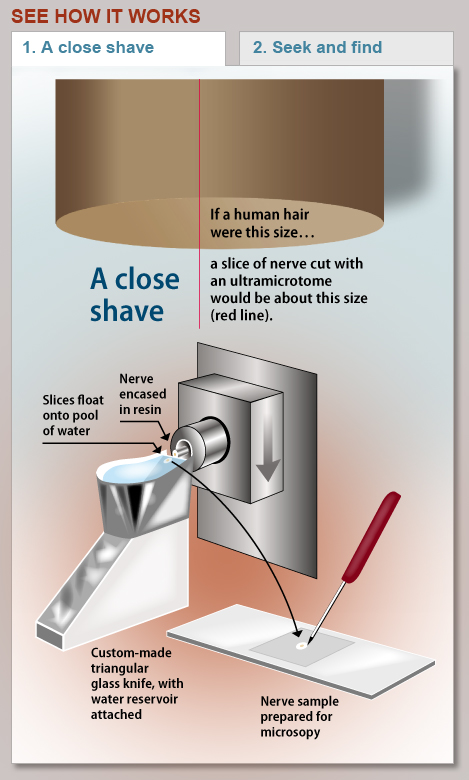

Though modern ultramicrotomes use diamond knives, Hunter prefers the instruments and methods he perfected early in his career. “I’m old school,” Hunter says with a laugh. “If I had to switch instruments, I think I would just leave.”

The glass knives he makes himself are sharper than diamond, but more fragile. After only a handful of cuts, the edge dulls and the knife must be replaced. Neat rows of triangular glass knives sit on Hunter’s bench top, waiting to be mounted in the ultramicrotome to slice cross sections of nerves embedded in a hard epoxy resin.

A microtome is termed “ultra” when it cuts samples even thinner than the already thin sections cut by regular microtomes. With his vintage ultramicrotome, Hunter can cut sections as thin as 60 nanometers. That’s 1,000 times thinner than a human hair. Indeed, the sections are so thin they cannot be handled directly, but are collected on the surface of a tiny pool of water flush with the glass cutting edge. Floating on the water’s surface, the sections appear in vibrant colors — tiny postage stamps of shimmering blues, greens, or purples depending on their thickness. The same complex optical physics is at work in the rainbow of colors seen in thin films of oil floating on street puddles.

Hunter scoops these samples up with a platinum wire loop and mounts them on glass slides for light microscopy or on metal grids for the extreme close-up view provided by an electron microscope.

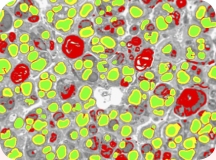

In the images of nerve cross sections, the average person sees wiggly lines, circles with thick borders, circles with thin borders, dots and splotches of all shapes and sizes. But to Hunter, each nerve section tells a story.

“This is a crush injury,” he says, pointing to the small circles in one of the images.

When a nerve is crushed, the layer of insulation surrounding the nerve fibers, called myelin, gets thinner. But the axon, the “wire” that transmits electrical signals, stays the same. As the myelin sheath thins, the axon’s electrical signals slow down.

“This axon here is dying,” he explains. “It’s being torn away from the myelin. Some scientists may not count these accurately because they can’t distinguish between viable and nonviable axons.”

Originally, Hunter counted axons and examined nerve sections entirely by hand. Seeking to speed up his process, he found help from an unlikely source: He co-opted an imaging system intended for examining metals — iron, steel, alloys and ores — and wrote his own programs to make the system analyze nerve cross sections instead.

“I don’t even know how he came up with that,” says Mackinnon. “But for every new operation that I develop, Dan looks at the nerve regeneration in animal models first and tells me whether the new technique worked.”

A lab apart

Hunter’s methods have proven so comprehensive that researchers at other universities have purchased the metallurgy software platform to use with his custom peripheral nerve programs. Groups at the University of Pittsburgh, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan are now using Hunter’s system in their own nerve investigations.

“Dan has been doing this type of analysis on nerves his entire career,” Mackinnon says. “He has really focused on that with tremendous intellect and passion and become extraordinarily expert in it.”

Hunter calls these meticulous methods the gold standard in quantifying the state of a nerve, whether healthy, injured or regenerating.

“It gives us far more information than any other tool to assess nerve regeneration,” he says. “Other groups might choose to only count axons. And I’m not saying that’s right or wrong. We are just extremely comprehensive when we look at nerve injury and regeneration. That’s one aspect of our lab that sets us apart.”

Applied in the O.R.

The ulnar nerve has been damaged in the upper arm. Click the nerve to see a surgical option based on research done in the peripheral nerve lab.

COMPANION FEATURE

Step-by-step

The peripheral nerve team develops a website to train surgeons and health care professionals around the world.