Graham A. Colditz, MD, PhD, reviews epidemiological research with

Victoria V. Anwuri, MPH, project manager at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center.

Nearly 60 percent of all cancers are preventable.

A staggering statistic — especially when some prevention strategies, such as exercise and eating right, seem within our control. But cancer’s bigger picture is far more complex, say researchers at the School of Medicine. They assert that society-wide commitment is needed to reduce this insidious disease.

Change is the focus of Graham A. Colditz, MD, PhD, chief of the Division of Public Health Sciences at the School of Medicine and an evangelist for cancer prevention.

Whether advancing tobacco regulation or promoting transdisciplinary laboratory research to accelerate our understanding of disease, Colditz and his public health colleagues are urging all members of society to reexamine the status quo — from urban planning to medical research funding —and make changes that could reduce the burden of cancer in the future.

Such transformation will require nothing short of changing hearts and minds: countering skepticism — even in the medical community — that cancer is preventable; planning decades-long research programs; encouraging early interventions and research into preventing disease, rather than just treating chronic conditions; and designing communities and public policy to support active lifestyles, provide easy access to healthy foods, and discourage unhealthy behaviors.

“We actually know an enormous amount about the cause and preventability of cancer,” says Colditz, the Niess-Gain Professor of Surgery and associate director of Prevention and Control at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. “It’s time we made an investment in implementing what we know.”

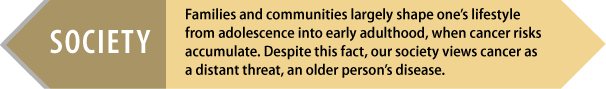

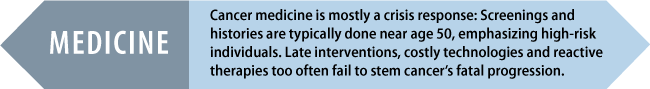

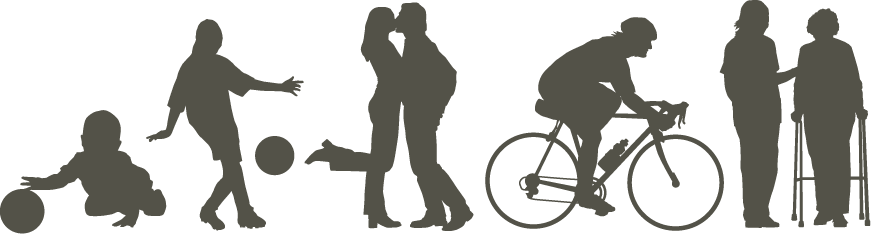

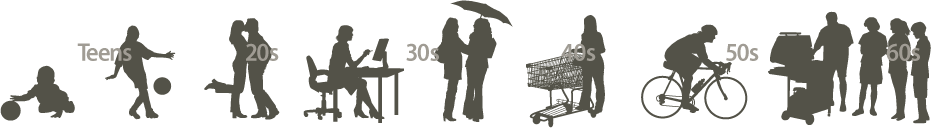

For most of human history, people died of causes other than cancer. During the last half-century, however, sweeping social changes have increased cancer’s burden. We focus most of our limited resources on reactions to the disease late in life.

But at an early age, the stage is already being set for the costly crisis it will later become — its potentially deadly individual impact, its detriment to society as a whole.

Lifestyle/risk accumulates during early years »

Cancer begins undetected in midlife »

Medical care may be powerless to stop the disease »

-

Process spans decades

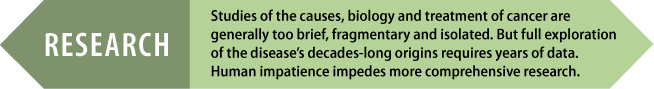

New genetic research suggests that the seeds of some cancers are sown early — perhaps two decades or more before a doctor might make a diagnosis.

“We used to focus on diet, activity and weight in the year or two before the patient was diagnosed,” Colditz says. “But now we know the process spans decades. More recently, we’ve started to examine what I would call the more appropriate time frame for looking at lifestyle and habits — adolescence and early adult years — 20 or more years before diagnosis.”

Participating in events such as the Prostate Cancer Community Partnership, epidemiologist Graham A. Colditz, MD, PhD, left, aims to improve understanding of cancer prevention at the community level. Colditz believes that scientists should partner with communities, respond to their needs and not set agendas from afar.

Such research supports the idea that even small changes in lifestyle may have a large impact over a lifetime in preventing cancer. That’s the idea behind Siteman Cancer Center’s “8 Ways” campaign, eight simple guidelines to lower cancer risk.

One example of research into the impact of early life on cancer risk is Colditz’ work on benign breast disease in adolescence. In a recent study reported in the journal Cancer, Colditz and colleagues showed that adolescent girls with a family history of breast disease — either cancer or the benign lesions that can become cancer — have a higher risk of developing benign breast disease as young women than other girls. And unlike girls without a family history, this already elevated risk rises with increased alcohol consumption.

“This points to a strategy to lower risk — or to avoid increasing risk,” he says, “by limiting alcohol intake, especially in adolescence and early adulthood.”

-

All in the family

This type of information demonstrates the value of knowing a patient’s family history early.

“Many primary care providers assess family history at age 50, which is a bit late,” says Colditz. “If you’ve got a family history of cancer, you need to start screening earlier.”

Knowledge is power: Health communication researcher Kimberly A. Kaphingst, ScD, explains why it is essential for individuals to know their family’s health history and talk about that information with their doctor. If cancer is a part of that history, early screenings may save lives.

Since knowing family history is so important for appropriate screening, health communication researcher Kimberly A. Kaphingst, ScD, assistant professor of surgery, hopes to simplify the process and make it more useful for patients. Like a symbol-filled family tree, the traditional tool used for assessing a family’s history of disease is known as a “pedigree.”

“If you’re used to reading the code, you can glance at a pedigree diagram and gather an immense amount of information,” Kaphingst says. “But for people who don’t see them every day, it can make things unnecessarily complicated.”

In one study, Kaphingst is asking whether a story-based approach is more effective for gathering information about a patient’s family history.

“We tried to design an alternative to the pedigree tool, one that is more focused on family stories,” she says, “to provide concrete examples of how you might actually have a conversation with your family about health history and record that information.”

-

Eliminating disparities

Even without a detailed family history, some broader groups are known to be at higher risk of developing cancer than the general population. Siteman Cancer Center’s Program for the Elimination of Cancer Disparities (PECaD) is aimed at narrowing this gap.

“Although the racial disparity is declining in cancer death rates, it is still 32 percent higher in African-American men and 16 percent higher in African-American women than in other racial and ethnic groups,” says epidemiologist Bettina Drake, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of surgery.

Community members like Dewey Helms, left, Isadore M. Wayne, standing, and Leon E. Ashford work with epidemiologist Bettina Drake, PhD, MPH, to conduct research groups and then analyze data in an effort to understand the barriers to, and improve strategies for, research participation among minority groups.

In an effort to lower these rates, PECaD investigators are working with the local community, including churches, health clinics and public libraries, to get the word out about cancer screening and to encourage members of minority groups to participate in ongoing research.

“We’re doing focus groups among African-American men to determine what barriers there might be in the decision to donate tissue for clinical studies,” Drake says. Such repositories serve as tools that may help shed light on the reasons why African-American men develop prostate cancer at higher rates than other men.

“We’re very interested in looking at diet, exercise and other behavioral factors in combination with a person’s genetics,” says Drake. “If someone has a genetic predisposition to prostate cancer, perhaps we can encourage him to do something that might stave off the disease or its recurrence.”

-

Benefits beyond prevention

One such approach might be regular exercise. A sure benefit seen for prostate cancer patients is the improved quality of life after treatment for those who are more physically active.

“Our preliminary research suggests that men who are active, even if they are overweight or obese, have better urinary function after prostate surgery than men who are inactive,” says epidemiologist Kathleen Wolin, ScD, assistant professor of surgery.

Any exercise — even as little as 30 minutes of walking per day — can yield big health benefits. Kathleen Wolin, ScD, right, discusses the health benefits of physical activity with prevention study participant Virginia K. Jordan at the BJC WellAware Center on the Washington University Medical Center campus.

Wolin’s work also has shown that exercise can reduce the risk of colon cancer in both men and women. There is evidence that it reduces breast cancer risk as well.

And it doesn’t have to be intense exertion. Thirty minutes of walking per day shows a measurable benefit in reducing the risk for a number of chronic diseases.

“That’s one of the great things about prevention,” Wolin says. “One lifestyle choice can have a beneficial effect on multiple cancers as well as other chronic diseases. Not only does physical activity reduce the risk of colon and breast cancer, it also reduces risk for heart disease, stroke and diabetes.”

Indeed, Colditz emphasizes that the “8 Ways” are more than cancer prevention strategies: They improve overall quality of life.

“A patient in one of our trials talked about what it was like to go from not exercising at all to being able to walk around a football field,” Colditz says. “She described the program as ‘lifesaving.’”

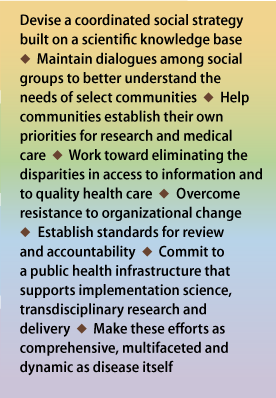

A comprehensive, lifespan vision

More than half a million people die in the United States every year due to cancers we already know how to prevent. Applying that knowledge could prevent more than half of all cancer. Addressing this problem requires refocusing and coordinating efforts at multiple levels: the conduct of research, the delivery of medical care and the foundation of health policy. An individualistic culture must find ways to nurture healthy communities as the basis of living better lives.

Prevention in action

Tobacco use poses the single largest cancer prevention problem — and potential solution. Quit, and year by year the specter of cancer subsides. Better yet, never start. Comparing Utah’s percentage of smokers to Kentucky’s helps explain the Bluegrass State’s higher lung cancer mortality rate.

Commitment to change

Through our relationships, advocacy and support of social programs, we can make a profound difference. Simply practicing the eight basic ways to live healthier promises more than preventing cancer within. It offers a much broader hope for revitalizing our society.

Maintain a healthy weight

Exercise at least 30 minutes a day

Quit or never start smoking

Eat a healthy diet

Consume alcohol moderately if at all

Protect yourself from sexually transmitted diseases

Protect yourself from the sun

Get appropriate cancer screenings

Learn more about prevention

The Institute for Public Health is a university-wide initiative designed to transform our approach to public health and partnership with the community. publichealth.wustl.edu

The Division of Public Health Sciences contributes to the goals of preventing disease, promoting health and improving access to quality care. publichealthsciences.wustl.edu

Read about eight lifestyle recommendations that can lower risk for cancer as well as heart disease, stroke, osteoporosis and diabetes. siteman.wustl.edu/8ways.aspx

View a series of videos that detail the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center's 8 Ways to lower cancer risk. siteman.wustl.edu/ContentPage.aspx?id=5171

Story by Julia Evangelou Strait | Information graphics by Eric Young

Photos by Robert Boston, Tim Parker and Ray Marklin