Neuro-oncology Fingerprints

Defining the unique genetic characteristics of brain tumors may lead to better diagnosis and therapy

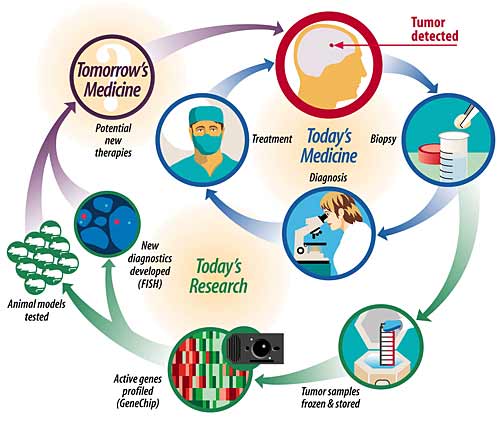

Above: By studying the unique genetic signatures of tumor tissue, today's research paves the way for tomorrow's medicine.

As a fingerprint distinguishes an individual, each cancer's genetic signature is unique.

![]()

Brain cancer—the very words evoke fear. And for good reason. Despite advancements in detection and treatment of other tumor types, brain cancer continues to be one of the deadliest forms of the disease. But thanks to technological advances and scientific breakthroughs, the field is ripe for progress.

That's why, roughly five years ago, neuro-oncologists at the School of Medicine joined forces to tackle this most formidable of cancer frontiers. Today, their multidisciplinary approach incorporates a wide range of clinical and laboratory expertise.

With access to the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center and cutting-edge technologies, researchers at Washington University are pooling their resources with several goals in mind: to understand how and why cells grow abnormally and divide uncontrollably in order to develop better treatments; to discover ways to predict who will become sick so that early detection is more feasible; to appreciate differences between types of brain tumors so that more targeted treatments can be applied to specific tumors, and to improve surgical strategies.

Difficult and deadly challenges

According to the American Brain Tumor Association, about 13,000 Americans die each year from brain cancer. Brain tumors are the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in people ages 20-39 and are even more common in adults ages 40-70. They are the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in children.

In the normal body, cells constantly divide, grow and die. These processes are genetically hard-wired by a number of critical genes that maintain the balance between cell life and death. But sometimes a cell escapes from the programmed routine of development and death—it grows rapidly and abnormally and forms a cancer. These abnormal cells perpetuate and accumulate genetic mutations and then can metastasize (grow and spread) to other areas of the body.

The brain poses a unique set of challenges. Early detection of brain cancer is more difficult—and arguably more important—than in most other organs. Despite improvements in brain imaging, it is not cost-efficient to offer routine brain scans, even for individuals over the age of 55 who are at the greatest risk. Symptoms often are subtle or difficult to diagnose. These tumors can therefore grow undetected for many years and become resistant to therapy.

Late diagnosis is made even more frightening by the fact that the brain is more difficult to treat than any other organ. It has its own protective wall, the blood-brain barrier, that keeps out unwanted elements. Unfortunately, it often also blocks chemotherapy and radiation treatment, and poses a unique challenge for surgery.

In theory, the best way to get rid of an unwanted bundle of cells is simply to remove it. But, once again, the brain is defiantly difficult. It is a complex system of interwoven cells, each specialized for different but equally vital functions and each connected to other cells through an intricate network of communication. Even if the tumor hasn't begun to spread, the surgical risks could outweigh the benefit.

To more effectively treat this devastating cancer, physicians and scientists are working to develop tumor-specific therapies and to discover ways of identifying individuals who are most likely to respond to a given treatment.

Banking on the future

Early diagnosis of brain cancer is as challenging as it is critical. Though there are some genetic or immune diseases that predispose certain individuals to brain cancer, as well as evidence that points to environmental risk factors like radiation, few cases fall into any such category. For the most part, there is no way to predict who will develop a brain tumor.

For several years, surgeons at the School of Medicine have been collecting frozen samples of tumor tissue from consenting patients and saving them in the Siteman Cancer Center Tumor Repository directed by Mark A. Watson, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pathology. After a biopsy is done, a sample of tissue can be stored indefinitely for experimental analysis.

“By successfully freezing cells, you can get a series of samples and go back to look at them when the right tools are available,” says Keith M. Rich, MD, associate professor of neurological surgery, of radiology, and of anatomy and neurobiology, who uses the samples for his own research.

The goal of the tumor bank is to provide a resource of biological specimens that can be used to develop genetic profiles of brain tumors. In the same way that a fingerprint distinguishes individuals from one another, the genetic makeup of each specific type of tumor distinguishes it from other forms of cancer. With a large bank of tissue samples, researchers hope to understand the distinguishing characteristics between different tumors and to develop tailored treatment strategies for individual patients.

Taking the genetic inventory

To produce these molecular profiles for specific grades of brain tumors, researchers employ a genetic technology called GeneChip analysis. The technology, also referred to as DNA microarray, is provided by the Multiplexed Gene Analysis Core at the Siteman Cancer Center, led by Watson and William D. Shannon, PhD, assistant professor of medicine and of the division of biostatistics. It allows researchers a panoramic view of cancer gene expression, thousands of genes at a time.

“Technologies like the GeneChip provide us a unique perspective into the genetic domain,” says Watson. “We now can step back and take inventory on a larger scale, which nicely complements our traditional approach of examining suspect genes one at a time.”

The resulting, comprehensive list of active genes is useful both for basic science and clinical research: It helps to identify groups of patients that might respond to different treatments already available and also leads to frequent discoveries of new genes that can then be examined more critically in the laboratory. Watson and his colleagues already have begun to classify tumors using this method and are compiling genetic profiles that may help predict clinical behavior and response to therapy.

In this pursuit to distinguish unique characteristics of particular types of tumors, Arie Perry, MD, assistant professor of pathology, enlists the help of another useful technique, fluorescence in situ hybridization, or FISH. Perry uses specially designed fragments of DNA to probe individual tumors for specific genetic regions of interest. These DNA probes deposit a red or green fluorescent dye wherever those genetic regions are present and these colored signals, or dots, are then visible through a microscope.

Normal cells have two copies of each gene. Once a gene has undergone FISH, Perry can simply examine a tissue sample and count the dots: two red dots or two green dots signify that the gene of interest is intact, or healthy; numerous dots suggest that the gene is amplified, or more active than it should be; fewer than two mean that the gene has been deleted off the chromosome. Either of the latter two scenarios might indicate tumor growth.

“In the future, I think we'll still be looking under the microscope to make a diagnosis,” says Perry. “But by adding techniques like FISH, we'll be able to get a lot more information from our diagnosis that will be useful to the patient.”

His optimism is well-founded. For years, researchers have been puzzled by one form of brain tumor called oligodendroglioma. Though most patients with oligodendroglioma respond well to chemotherapy, a significant percentage do not. Using FISH, Perry and others have discovered that tumors with specific genetic losses —fewer than two red dots—on two different chromosomes, 1p and 19q, are more likely to respond to therapy and yield a better prognosis.

Unlocking the secrets of the cancer cascade

Determining which patients will respond to treatment is just the beginning. To really get to the bottom of brain cancer, scientists need to understand why tumors differ from one another and then develop a treatment alternative specifically targeted to the resistant types. At the heart of cancer research is the desire to understand the cascade of genetic signals and mishaps that allow a cell to become cancerous. Unfortunately, research with human tumor specimens cannot sufficiently answer this question.

It is impossible to determine from a diseased cell which genetic changes were necessary and sufficient for that cell to become cancerous. Techniques like GeneChip analysis can provide a list of changes that occurred, but many of them might have been merely incidental.

Using cells from animals such as mice, researchers can study pre-cancerous cells and watch as they form a tumor. They also can systematically manipulate the genes of a cancerous cell to see, from the other side of the equation, which manipulations might reverse or improve the process.

“With a mouse, we can make single, surgically placed genetic changes and then find out what the consequences of these alterations are on brain tumor formation,” explains David H. Gutmann, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology. “Animal models also present the opportunity to test potential therapies within the natural context of a living creature.” With humans, scientists are restricted to studying the effects of new treatments on cells in a petri dish, removed from the living environment.

Mouse models already have helped Gutmann and his colleagues begin to understand the most common—and one of the most deadly—types of brain cancer, astrocytoma. Patients with a genetic disease called Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) often develop astrocytomas. The gene mutated in these patients, NF1, helps regulate a molecule called RAS. In collaboration with researchers at the University of Toronto, Gutmann's team has developed a strain of mice, called B8, that has more RAS turned on in its astrocytes. The mice get sick and die of classic astrocytomas at around 3 or 4 months of age.

By manipulating the activity of potential culprit genes that may be altered during tumor development, the researchers hope to isolate the correct sequence of necessary changes required for the cell to become cancerous.

Such research into the underlying mechanisms of brain cancer, combined with the latest diagnostic tools, sets the stage for a new era in neuro-oncology therapeutics.

“Using this multidisciplinary approach, we already

have made great strides toward piecing together this complex puzzle,”

says Gutmann. “Underneath all the laboratory and clinical work is

the hope that we will make life better for patients with brain cancer.”

![]()

|

Minimally invasive surgical procedures may prove safer While researchers labor to uncover new diagnostic and treatment strategies for brain cancer, exciting surgical options already exist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. One advancement is a technique that uses the power of magnets to maneuver around healthy and indispensable areas of the brain. The technology, the Magnetic Surgery System (MSS), was first tested on a human patient in 1998 at the School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “This is a fundamentally new way of manipulating surgical tools within the brain that promises to be minimally invasive,” says Ralph G. Dacey Jr., MD, the Edith R. and Henry G. Schwartz Professor and head of neurological surgery. “It should be a safer way of doing brain surgery because it allows us to use a curved pathway to reach a target. Therefore we can go around sensitive structures, such as those that control speech or vision, instead of going through them.” Another alternative to traditional surgery is the Gamma Knife. Despite its name, the Gamma Knife is not a knife at all. In fact, the whole point of this tool is to avoid making an incision. Instead, the machine surrounds a patient's head and emits 201 beams of gamma radiation from multiple directions. Alone, each beam is harmless. But when they converge at a particular point, their combined strength is sufficient to treat a diseased mass of tissue. Surgeons can therefore target a specific area of the brain and avoid damaging cells along the way. |