Physician, Manage Thyself

Having accepted a personal mission when first they donned their white coats, doctors now find it takes business acumen to fulfill that mission. It’s time to hang another diploma...from the Olin School of Business.

“No margin, no mission. If we do not break even or

better, we can't fulfill our mission. We have to be responsible stewards

of health care resources.”

—STEVEN B. MILLER, MD

“Having a broader understanding of business...is very

important in helping to shape the future of health care.”

—RONALD J. CHOD, MD

![]()

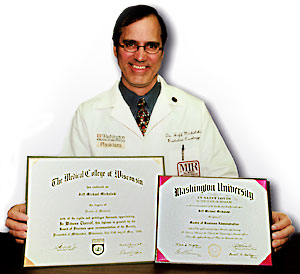

Jeff M. Michalski—MD, and EMBA! Michalski is framing both degrees for his office in the new Center for Advanced Medicine.

IN MEDICAL SCHOOL I was taught to care for the patient," observes Jeff M. Michalski, MD. "In business school I was taught to care for thousands of patients."

The distinction that Michalski sums up so succinctly— and the critical need for management skills in medicine— are increasingly noted in the medical community, where growing numbers of physicians and other health care professionals are turning to business education to help them cope with escalating costs and expanding complexities in health care delivery.

"Health care is a trillion-dollar industry, a huge percentage of our gross national product," says Steven B. Miller, MD, associate professor of medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s vice president and chief medical officer. "But historically it’s been run almost as a cottage industry. It takes much more capable management."

Health professionals have an invaluable partner in the Olin School of Business at Washington University in St. Louis. In collaboration with the School of Medicine, Olin has tailored non-degree programs and a health services management concentration in the executive master of business administration (EMBA) degree program to help doctors and others navigate the business world. Physicians also often pursue an EMBA without the health care focus.

Michalski, an assistant professor of radiation oncology, is clinical director of the division of radiation oncology and medical director of the clinical trials office at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center. As he sees it, physicians must acquire contemporary business skills if they are not to lose control over treatment decisions.

"We need to be just as wary of costs as insurance companies," he says. "If we can work with them to keep costs down, we’ll be much more credible to work with."

Michalski, who completed his EMBA with a health services management concentration in March 2001, is one of a growing number of physicians who are using business tools to achieve new efficiencies and deliver better care. His Olin classes in operations, for instance, have helped him streamline patient services.

"Operations showed me how to deal with sorting people into different queues for different types of treatment, ensuring that physicians can see the types of patients they need to see without schedule conflicts, managing complex groups of individuals." These measures eliminate overlapping services, save time for patients, and improve the bottom line.

Containing costs has an even broader significance, according to Ronald J. Chod, MD, who enrolled in the EMBA program last fall. "Clearly, medical cost inflation is once again escalating," Chod points out. "Simultaneously, the population is aging, new and expensive therapies are evolving, and an increasing number of businesses are walking away from providing health insurance. Yet provision of care is still highly fragmented, and potentially wasteful.

"The economy will only be able to support limited expenditures on health care. It’s going to be extremely important that we harness all of our resources to provide science-based treatments and preventive therapies," Chod continues. "Having a broader understanding of all the business components that are part of health care is very important for helping to shape its future."

Miller puts it very simply. "No margin, no mission," he says. "If we do not break even or better, we can’t fulfill our mission. We have to be responsible stewards of health care resources."

Once a researcher in renal medicine with a productive bench science career, Miller agreed in 1995 to head up the renal network for the newly created BJC hospital system. As it turned out, the decision was the first step on a new professional path.

Miller acquired additional management roles; in 2000, he became vice president and chief medical officer at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, where he oversees 1,500 people and a $150 million budget. He enrolled in the EMBA program to better equip himself for the job.

Chod, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, has management responsibilities as well. He is associate vice chancellor for clinical affairs at the medical school. He holds two additional positions, one as executive director for development of the Faculty Practice Plan and the other as executive director for network development of the Washington University Physicians’ Network. The need for business acumen in those positions is what drew him to the EMBA program.

Chod believes that cost containment will require broader coordination across the health care landscape. "The future of health care requires greater organization of care among physicians and other providers," he says. "Right now, if you’re a patient with multiple medical conditions, your care could be provided by a half dozen to a dozen different physicians.

"Each of those physicians has his own medical records, with redundant, and sometimes conflicting, information. So the fragmented practice of medicine today leads to mistakes and inefficiency."

Chod has found his accounting course especially useful. "Cost accounting and measuring component activities that go into a process help to determine where changes can be made to most efficiently deliver service," he says.

He also is enjoying course work in organizational behavior, as did Michalski. "Organizational behavior skills are critical," Michalski says. "Managing people is the really hard thing. Sometimes you have to make difficult decisions for the sake of the group."

For Miller, perhaps the most important lesson at Olin has been strategic thinking, expanding perspective on problems. "You view things from a position of being opportunistically informed," he says. "You will take advantage of the opportunities, driven by information."

He cited medical records as an example. "By making a strategic decision to spend an extra $1 million last year," he says, "we were able to dramatically decrease our billing cycle. We had to spend extra dollars in coding and chart management, but by spending those extra dollars, we were able to get our bills out the door and improve our cash flow—resulting in a multimillion-dollar benefit."

Skeptics might question the bottom-line business orientation that views people as customers rather than patients. But Michalski argues that medical care would improve if physicians were to adopt a customer-service approach. Waiting-room time would go down, doctors would be more accessible to their patients, services more evenly distributed across a region, rather than concentrated in a huge urban center.

According to Pam Wiese, assistant dean and director of executive MBA programs, the program also teaches health care professionals to spot business trends that will affect their organizations—everything from consolidation in hospital ownership, to the Internet and its creation of both highly educated and often miseducated patients, to outsourcing, to reduced levels of employer health care funding.

The doctors rave about their academic experience at Olin. "The program is everything I hoped it would be and more," observes Chod. Says Miller: "As an academician, it has been interesting for me to learn how another school teaches. The program’s use of Internet resources is very progressive, and the quality of the faculty is phenomenal."

Physicians also are enthusiastic about the program’s team approach. At the outset, students enrolled in either the straight EMBA or the EMBA with a health services management concentration are grouped into teams, which remain together for the program’s duration.

"I have these brilliant teammates," Miller says. In his group are executives from Anheuser-Busch, Monsanto, Emerson and Bass Hotels. "I can learn all sorts of things about operations, service, human resources, accounting —the spectrum of business activities from people who are actually succeeding at it."

The teams also are essential to get the work done, Chod adds. "Different people on the team bring different skills, so if you have a strong finance person and a strong marketing person, you’re complementing yourselves to take the work to a higher level."

Michalski agrees. "We ended up teaching ourselves a lot," he says.

Michalski, unlike Miller and Chod, chose the health services management concentration rather than the straight EMBA, so his class was made up of professionals in pharmacy, hospital administration, nursing and the pharmaceutical industry, as well as physicians. "My class of maybe 30 people included professionals from all walks of health care," he says. "When we talked about things, we’d get 30 different perspectives."

Change in health care delivery is inevitable, these doctors

agree. Whether physicians will play a role in shaping those changes is

less assured. "The more physicians are able to understand business,"

Chod asserts, "the better they’ll be able to interact with decision

makers. So business education for key physicians should help bring health

care to a new level." ![]()

|

A quicker education—“Inside the Business of Medicine” Olin presents four short, yet in-depth courses—the busy physician’s business study In this day and age," George M. Cesaretti contends, "you can’t deliver good medicine without being business savvy." But Cesaretti, assistant dean and director of non-degree executive education at the Olin School of Business, also knows that not every doctor needs an MBA to deliver good care successfully. Cesaretti and Stephen Kraft, MD, Olin’s director of continuing physician business education, have developed programs for practicing physicians. The series will help physicians confront questions such as: What does your practice look like as a business––its finance, strategy, structure, organization? What sort of contracts does it hold? How does it negotiate those contracts? Who supplies it? How does it get paid? Who are your partners? Who are your competitors? Topics include: • Business and Management Strategies for Medical Practice, • Financial Management for Medical Practice, • Quality in Health Care, and • The Art of the Deal: Negotiation and Conflict Resolution Strategies for Physicians and Health Care Providers. "Each course we’re offering is designed to attack some major facet of the medical practice," Cesaretti says. New courses will follow as the program gathers steam. Kraft and Cesaretti discovered that practicing physicians have non-course needs as well, so they established a Business of Health Care Journal Club, where members meet to discuss articles and research on current health-related business topics. And the school is offering symposia on health services management issues. One in March addressed mobile commerce in health care. "Medicine is not on another planet," observes Kraft, an Olin EMBA graduate. "While it does have unique features, it’s not so unique that the laws of business don’t apply. Business education can help you provide better medical care." |

![]()