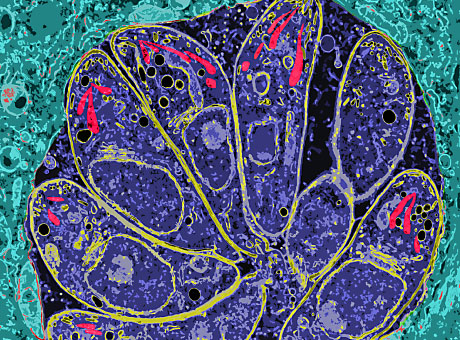

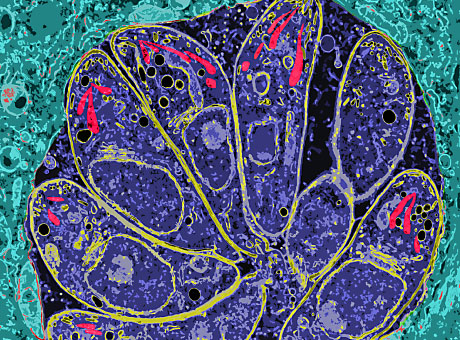

A newly identified protein may help stop the toxoplasma parasite, shown in purple and pink in the color-enhanced image above.

A newly identified protein may help stop the toxoplasma parasite, shown in purple and pink in the color-enhanced image above.

Researchers at the School of Medicine have identified a parasite protein that has all the makings of a microbial glass jaw: It’s essential, it’s vulnerable and humans have nothing like it, meaning scientists can take pharmacological swings at it with minimal fear of collateral damage.

The protein, calcium dependent protein kinase 1 (CDPK1), is made by Toxoplasma gondii, the toxoplasmosis parasite; cryptosporidium, which causes diarrhea; plasmodium, which causes malaria; and other similar parasites known as apicomplexans.

In the May 20, 2010 issue of Nature, researchers reported that genetically suppressing CDPK1 blocks signals toxoplasma uses to control its movement, preventing it from moving in and out of host cells. With researchers from other institutions, they identified a compound that blocks CDPK1.

“Kinases are proteins that are common throughout biology, but the structures of CDPKs in apicomplexans much more closely resemble those found in plants than they do those of animals,” says senior author L. David Sibley, PhD, professor of molecular microbiology. “We showed that these differences can be exploited to identify potent and specific inhibitors that may provide new interventions against disease.”

Infection with toxoplasma is most familiar to the American public from the recommendation that pregnant women avoid changing cat litter. Cats are commonly infected with the parasite, as are many livestock and wildlife. Humans also can become infected by eating undercooked meat or by drinking water contaminated with spores shed by cats.

Toxoplasma infections are typically asymptomatic, only causing serious disease in patients with weakened immune systems. In rare cases, though, infection in patients with healthy immune systems leads to serious eye or central nervous system disease, or congenital defects in the fetuses of pregnant women.

Sibley studies toxoplasma both to find ways to reduce human infection rates and as a model for learning about other apicomplexans, such as plasmodium, that are more significant sources of disease and death.

Cats are commonly infected with the parasite, as are many livestock and wildlife.

The new study, led by graduate student Sebastian Lourido, began as an effort to determine what CDPK1 does for toxoplasma. Researchers genetically modified the parasite, eliminating its normal copy of CDPK1 and replacing it with a version of the gene that they could turn on and off. When they turned the new gene off, they found that they had paralyzed the parasite, preventing it from moving and from breaking into and out of host cells. Turning the gene back on restored these abilities.

Sibley and Lourido plan to learn more of the details of how CDPK1 works, using toxoplasma as a model to study the functions of parasites and how they differ from human cells. The successful toxoplasma inhibitor is now undergoing further testing in animals to see if it can eventually be adapted for clinical use to prevent infection in humans.