Parkinson’s disease first began to affect Susan Tinzmann, a secretary from Springfield, Ill., at the age of 47. She notes that tremor, the most infamous Parkinson’s symptom, was never her biggest problem.

“I knew my walk was funny, and just in general felt there was something weird going on,” she recalls.

Tinzmann eventually came to the Parkinson’s Disease Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, where she was diagnosed with the disorder.

“You functioned very well for a few years after diagnosis,” her husband, James Tinzmann, recalls. “Then a few years later, your movement had become so limited that you started doing things like calling me on the phone to ask me to get something out of the filing cabinet for you.”

The Tinzmanns can laugh about those days now because Susan’s symptoms, never adequately controlled during years of trying different medications, are now significantly eased by an implant known as a deep-brain stimulator (DBS). The stimulator, which has been called a pacemaker for the brain, periodically jolts the brain with pulses of electric current.

“Since I’ve had the stimulator installed and programmed, I feel like I can get around a lot better and stay focused a little better,” Tinzmann says. “After spending some time on disability and social security as a result of Parkinson’s, I’m now looking for a job again.”

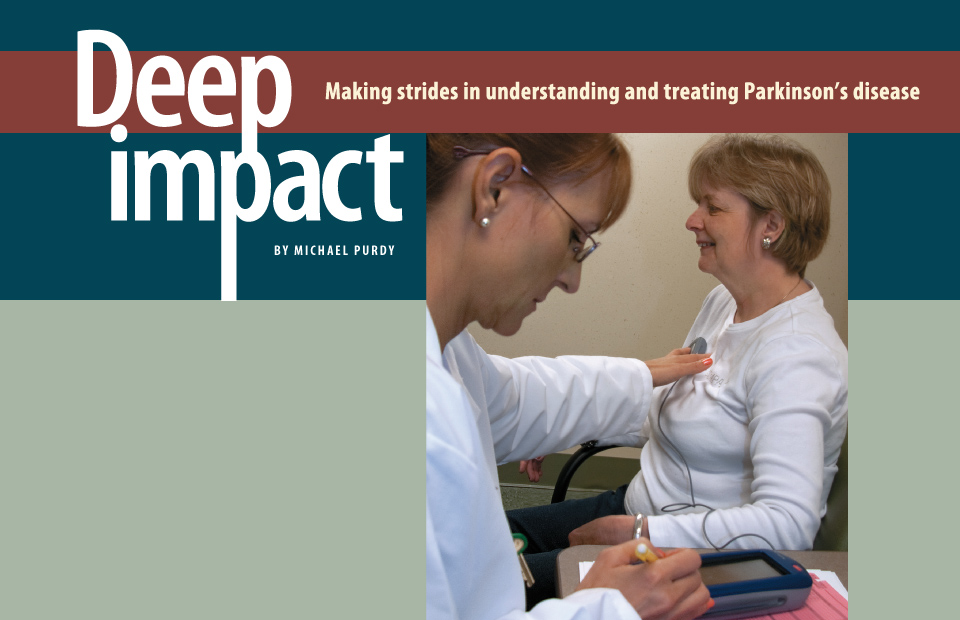

TIME FOR A TUNE-UP A deep brain stimulator (DBS), consisting of electrodes in her brain connected to battery-operated pulse generators in her chest, helps keep Susan Tinzmann’s Parkinson’s disease in check. As with all DBS recipients, Tinzmann receives regular evaluations and, when necessary, the pulse generators are reset, performed here by Dawn M. Lintzenich, RN.

Washington University researchers are leaders in efforts to learn how deep-brain stimulators affect the brain and how to fine-tune the installation and application of stimulators in order to maximize benefits and minimize side effects.

And those efforts are just one branch of a multidisciplinary campaign that is moving forward on multiple fronts in the battle against Parkinson’s.

While he’s pleased with the progress many patients are making with DBS, Joel S. Perlmutter, MD, head of the Movement Disorders Section in the Department of Neurology, is careful to emphasize that it’s an option to be considered only after the many different possible medication regimes for controlling Parkinson’s disease have failed.

Joel S. Perlmutter, MD

“As a doctor advising patients, I say, ‘If the pills work, don’t put two holes in your head,’” says Perlmutter, who also is professor of neurology, neurobiology, physical therapy, occupational therapy and radiology. “Surgery has serious risks, and maintenance of the implants also requires us to operate again years later to replace the batteries.

Perlmutter talks in quiet, soothing tones that contrast with the boundless energy and no-nonsense attitude he brings to patient care and research. Although initially highly skeptical of DBS, the evidence won him over.

He estimates 10 to 20 percent of Parkinson’s patients eventually go on DBS. Approximately 75 DBS installation surgeries are performed each year at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

The program is led by physician Samer D. Tabbal, MD, associate professor of neurology, and surgeons Keith M. Rich, MD, professor of neurosurgery, radiation oncology and neurobiology, and Joshua L. Dowling, MD, associate professor of neurological surgery.

— Joel S. Perlmutter, MD

How does DBS help? Thanks in part to studies by Perlmutter, Tamara G. Hershey, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry, neurology and radiology, and Kevin J. Black, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, radiology and neurobiology, scientists know that current from the DBS causes increased activity in regions of the brain connected to the subthalamic nucleus.

“If Parkinson’s is like getting persistent crank calls in the middle of the night on your bedroom phone, the deep brain stimulator is like taking that phone off the receiver and setting it on the table,” Perlmutter explains. “We believe the DBS causes the neurons to fire often enough that the abnormal firing patterns caused by Parkinson’s disease can’t get through.”

Precise placement

For many patients like Susan Tinzmann, this brings significant improvements in their ability to move and walk. For some, though, it also can bring impairments in higher cognitive functions. Patients can drive a car or play golf again, but they might not be able to program a computer or may experience trouble with their moods or their speech.

Could the placement of the electrodes be making a difference? Spurred in part by evidence that the subthalamic nucleus may have distinct functional areas, Tom O. Videen, PhD, research professor of radiology and neurology, Morvarid Karimi, MD, assistant professor of neurology, and others developed a method for much more precise assessment of where the DBS contacts are placed in the brain.

“We knew where the electrodes were going within a couple of millimeters, which was good enough for patient care,” Perlmutter explains, “but it wasn’t telling us what precise parts of the subthalamic nucleus were receiving the current and linking those parts to good results or side effects.”

The new approach to assessing electrode placement can only be definitively confirmed via autopsies of patients who had DBS implants, an effort that’s under way now. But after initial tests tentatively validated the method, Hershey and colleagues used it to show that stimulating the lower side of the subthalamic nucleus impaired a cognitive function known as response inhibition, which is important for impulse control and adaptive behavior.

“On another front, we had thought improvement in movement would mostly come from stimulating the top part of the subthalamic nucleus, but it turns out that effect is a kind of like a hand grenade,” Perlmutter says. “We could miss the subthalamic nucleus entirely and still get motor benefit.”

Researchers are now working to use brain scans to link stimulation of particular parts of the subthalamic nucleus to increases in activity in other parts of the brain. They hope to eventually produce a map of the subthalamic nucleus that highlights the areas where DBS impulses can do the most good while causing the fewest side effects.

Parkinson’s differs from Alzheimer’s

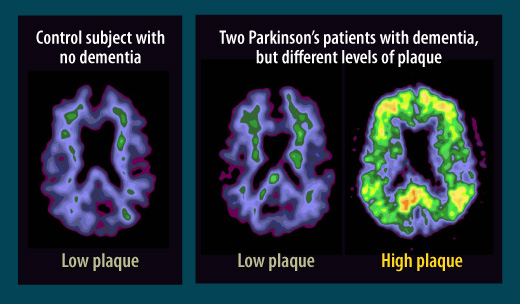

In assessments of the brains of Parkinson’s patients with dementia, scientists at first found a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease: plaque deposits called beta amyloid. But further studies showed that while some Parkinson’s patients with dementia have high plaque levels similar to those seen in Alzheimer’s, right, in other patients with Parkinson’s and dementia, center, the plaque levels more closely resemble those seen in healthy people who have neither dementia nor Parkinson’s, left. Scientists are seeking more clues to the causes of Parkinson’s-associated dementia.

Meghan C. Campbell, PhD

Factoring in dementia

One complicating factor in this mapping endeavor is the frequency with which Parkinson’s patients develop dementia.

“Dementia is fairly common in Parkinson’s patients,” says Meghan C. Campbell, PhD, research assistant professor of neurology. “If the patients live long enough after their initial diagnosis, dementia rates can rise as high as 80 percent.”

Post-mortem examinations of the brains of Parkinson’s patients reveal a great deal of abnormality in the substantia nigra, an area of the midbrain involved in movement, addiction and reward-based behavior. Normally, this area of the brain is darker than adjoining regions thanks to elevated levels of the pigment melanin; however, in Parkinson’s patients, this coloration is lost. Also lost are many of the neurons from this region that produce a neurotransmitter called dopamine.

The brains of most Parkinson’s patients contain clumps known as Lewy bodies that are made up of a protein called alpha-synuclein. In addition, scientists frequently find amyloid plaques, clusters of a protein fragment that are a defining characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease, in Parkinson’s patients who become demented.

“We used to think that if Parkinson’s patients lived long enough, they also developed Alzheimer’s disease,” Campbell says. “But what we’re now finding in our patients is that while many have amyloid plaques, they don’t have a second important characteristic of Alzheimer’s, which is tangles of tau protein, a component of nerve cell structure.”

The symptoms of dementia are also slightly different in Parkinson’s patients. While Alzheimer’s patients primarily lose established memories and the ability to learn new information, Parkinson’s patients often have problems with decision-making, planning, flexibility and other complex mental tasks.

“Individuals with Parkinson’s disease can have problems with memory, too, but at least in the early stages it’s a problem with what we call retrieval,” Campbell says. “We can ask them to learn a list of words, and they won’t be able to remember them a short time later, but if we give them hints, they can recall the words, indicating that they’ve created a memory but need help to access it.”

It’s not yet clear if the amyloid-clearing treatments being developed for Alzheimer’s will help to prevent dementia in Parkinson’s patients, since some get high levels of amyloid without ever becoming demented.

Campbell, Perlmutter and other Washington University researchers are conducting a long-range study to determine how Parkinson’s and dementia are linked.

“Dementia and the other cognitive problems that occur in some patients are the biggest unmet need in Parkinson’s disease now that we have DBS,” Perlmutter adds. “But I think we’re on the way to cracking these problems, too.”

Deep brain stimulator: a pacemaker for the brain

The periodic bursts of electric current from a deep brain stimulator (DBS) offer some control for Parkinsonian symptoms. The implantation procedure (1) involves drilling holes into the skull and using a needle to guide two wires with four electrodes each deep in the brain to the subthalamic nucleus (STN), a tiny, almond-shaped structure which is about 12 millimeters long.

ABOVE: Planning the procedure: Keith M. Rich, MD, left, and Samer D. Tabbal, MD. BELOW: Preparing the DBS wires and a surgical frame for precise targeting of the patient’s STN: neurosurgery chief resident W. Zachary Ray, MD, left, and neurosurgeon Keith M. Rich, MD.

In a second surgery performed a week later (2), the wires are connected to pulse generators and battery packs implanted under the skin, below the patient’s collarbone. The amount of current, frequency of pulses and other factors are adjusted through programming appointments over subsequent months.