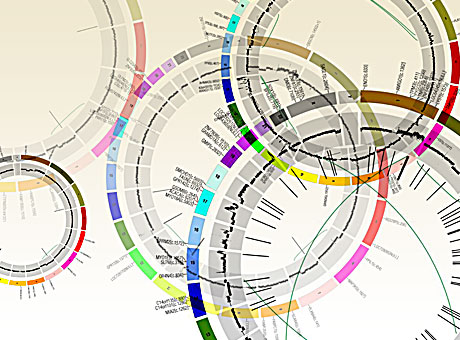

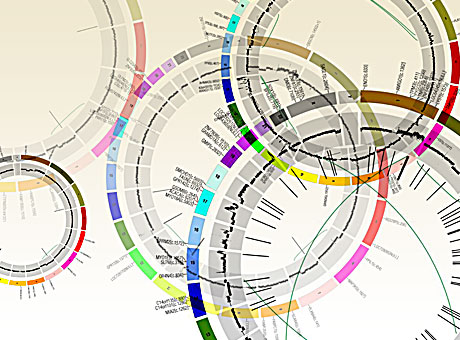

Circos plots, above, are a visual representation of genomic disruptions in the breast cancers studied.

Circos plots, above, are a visual representation of genomic disruptions in the breast cancers studied.

In the single largest cancer genomics investigation reported to date, Washington University scientists have sequenced the whole genomes of tumor cells and healthy cells from 50 breast cancer patients. Their work reveals the incredible complexity of cancer genomics and provides an important glimpse into new routes for personalized medicine.

The researchers studied DNA samples from patients with estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer. To identify cancer cell mutations, they compared tumor cell DNA to DNA of the same patients’ healthy cells. Repeating the sequencing about 30 times to ensure accurate data, they analyzed a massive 10 trillion base pairs of DNA.

In all, the tumors had more than 1,700 mutations, most of which were unique to the individual, says Matthew J. Ellis, MD, PhD, an oncologist at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine and a lead investigator on the project.

“Cancer genomes are extraordinarily complicated,” Ellis says. “This explains our difficulty in predicting outcomes and finding new treatments.”

Confirming previous work, Ellis and colleagues at Washington University’s Genome Institute found two tumor mutations that were relatively common. They also found a third, MAP3K1, that controls programmed cell death and is disabled in about 10 percent of these breast cancers. Only two other genes harbored mutations that recurred at a similar frequency.

In addition, they found 21 genes that were also significantly mutated, but at low rates — never appearing in more than two or three patients. Despite the rarity of these mutations, Ellis stresses their importance.

“Breast cancer is so common that mutations that recur at a 5 percent frequency level still involve many thousands of women,” he says.

Ellis points out that some rare mutations in breast cancer may be common in other cancers and already have drugs to treat them.

But such treatment is only possible when the cancer’s genetics are known in advance. Ideally, Ellis says, the goal is to design treatments by sequencing the tumor genome when the cancer is first diagnosed.

Although many mutations are rare or unique to one patient, Ellis says some can be classified based on common effects and could be considered together for a particular therapeutic approach.

Ellis looks to future work to help make sense of breast cancer’s complexity. But these highly detailed genome maps are an important first step.

“At least we’re reaching the limits of the complexity of the problem,” he says. “It’s not like looking into a telescope and wondering how far the universe goes. Ultimately, the universe of breast cancer is restricted by the size of the human genome.”

Ellis presented the work earlier this year at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.