John P. Atkinson, MD, and Kim Morey at the medical center's Ellen S. Clark Hope Plaza, named in memory of Ellen S. Clark, who succumbed to CRV in March 2010.

John P. Atkinson, MD, and Kim Morey at the medical center's Ellen S. Clark Hope Plaza, named in memory of Ellen S. Clark, who succumbed to CRV in March 2010.

For 20 years, Kim Morey wondered and worried if she had inherited the devastating disease that killed her father at age 49. But she continued with her life, getting married and having three children, in her hometown of Bentonville, Ark.

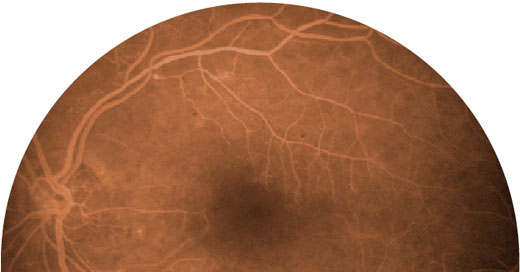

In her early 40s, Morey noticed a blurry spot in her eye. An ophthalmologist she saw reassured her that the spot was just a floater.

But when an MRI the next year discovered a lesion on her brain, Morey knew that she had inherited the gene that causes cerebroretinal vasculopathy (CRV).

Defining the disease

Morey’s doctor suspected the lesion was a sign of multiple sclerosis and referred her to a neurologist, but Morey had a special reason she wanted to see a physician at Washington University. She made an appointment with rheumatologist John P. Atkinson, MD, the Samuel Grant Professor of Medicine and the same doctor who had treated her father and through him identified CRV as a new genetic disease in 1988.

CRV is a rare disease that causes the progressive loss of tiny blood vessels, resulting in mini strokes in the brain. There is no treatment or cure. Patients, who usually have no symptoms until their early 40s, have a life expectancy of five to 10 years following diagnosis.

In a family that carries the CRV gene, 50 percent of the children will inherit the disease.

Atkinson and retinal specialist M. Gilbert Grand, MD, professor of clinical ophthalmology and visual sciences, initially identified CRV. Atkinson, Grand and their School of Medicine colleagues have been working for several decades to discover more about the disease. Through collaborations with physicians and scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands, they have identified 15 families in the world who are affected by CRV. However, it’s likely that more families may have CRV, says Atkinson, because it’s often misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis, a stroke or a brain tumor.

For many generations, Morey’s family assumed the deaths of her grandmother, her grandmother’s mother and other relatives were caused by brain tumors.

But because of the research conducted at Washington University, Morey’s three children, Ashton, 19, Tyrus, 18, and Nathan, 12, now could choose at age 21 to find out whether they have inherited CRV.

Morey’s only current symptoms of the disease are a few blurry spots in her eyes and fatigue.

“I really try to forget about the disease and live,” says Morey, who still enjoys her part-timejob as a business analyst at Pactiv, a parent company for Hefty. “We try to live in our house like my disease doesn’t exist.”

Taking action

Morey, her friends and extended family have taken on the challenge of raising money for CRV research. Through a sample sale at her company and two local golf tournaments in the past few years, they have raised more than $80,000 for what is being called the CRV Project.

Morey, who recently became a grandmother, hopes every day for a treatment that will extend her life. “I am very hopeful that there will be a cure in my lifetime, and I have complete faith that there will be a treatment or cure sometime soon,” she says. “But most importantly, I want something for my children and grandson.”

Rare diseases often get little attention and modest or no research funds. But Atkinson says that research is the key to unlocking the secrets of CRV.

“Through Kimberly Morey’s efforts, and those of her friends and family, resources are being provided for this to happen,” he says.

Funding from the CRV Project is being used to develop a mouse model of the disease, which will help Atkinson and his colleagues understand the pathophysiology of the disease and possibly find a treatment to slow its progression.

Additionally, the CRV Project has provided money for educational purposes. Atkinson and a number of other physicians recently presented a seminar for Morey’s extended family from three states and a St. Louis family affected by the disease. “We presented what we’ve learned about the disease and told them using genetic testing or in vitro fertilization could stop CRV,” says Atkinson.

Morey is grateful for the many years Atkinson has devoted to research on CRV and the care she receives from him. “I don’t think any doctor could be more dedicated to finding a treatment or cure for this, and I couldn’t be in better care,” she says. “I can’t imagine being in my shoes and not having him as my doctor.”

And as he continues to study CRV and treat patients battling the disease, Atkinson says he is inspired by Morey’s energy, perseverance and positive attitude.

“I have often thought about how I would behave if I knew I carried a gene for a rare disease that would shorten my life span and that I could pass on to my children,” he says. “I just hope that I would react in the courageous, open and remarkably productive manner of Kimberly Morey.”