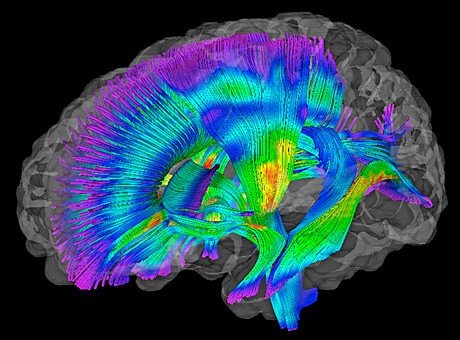

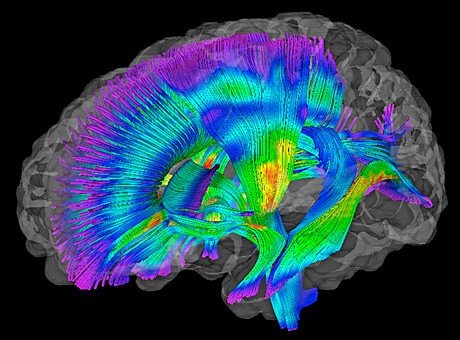

In this composite image of white matter pathways in the brains of infants at risk for autism, warmer colors represent higher fractional anisotropy (FA) readings. FA measures white matter organization and development.

In this composite image of white matter pathways in the brains of infants at risk for autism, warmer colors represent higher fractional anisotropy (FA) readings. FA measures white matter organization and development.

Researchers have found significant differences in brain development in infants as young as 6 months old who later develop autism, compared with babies who don’t develop the disorder.

The study, conducted by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and other centers, involved infants considered to be at high risk for autism because they had an older sibling with the diagnosis. The findings are published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

The new research, which relied on brain scans acquired at night while infants were sleeping naturally, suggests that autism doesn’t appear abruptly, but instead develops over time during infancy.

“We were surprised that there were so many differences so early in infancy,” says co-author Kelly N. Botteron, MD, who is leading the effort at the Washington University study site. “As this study moves forward, we may want to scan babies at even younger ages so that we can try to see how early this pattern is emerging.”

The new findings involved brain scans from 92 infants who had completed diffusion tensor imaging, a type of MRI scan, at 6 months and behavioral assessments at 24 months of age.

Study results represent an important first step toward the development of a biomarker for autism risk.

By 24 months, 28 of the infants met the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorders. Scans of the infants with autism revealed changes in the pathways that connect brain regions to one another. In particular, researchers found changes in multiple fiber pathways in the brain’s white matter.

The changes were identified using fractional anisotropy (FA), a process that measures white matter organization and development, based on the movement of water molecules through brain tissue.

“The idea that connections may be less organized in children with autism fits with our hypothesis,” says Botteron, a Washington University child psychiatrist at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “These children may have some changes in the brain’s gray matter, too, but the way their neurons speak to each other clearly seems to be disrupted.”

The study represents the latest findings from the Infant Brain Imaging Study Network, a $10 million initiative funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“It’s a promising finding,” says Jason J. Wolff, PhD, first author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow at UNC’s Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities. “At this point, it’s a preliminary, albeit a great, first step toward thinking about developing a biomarker for risk in advance of our current ability to diagnose autism.”