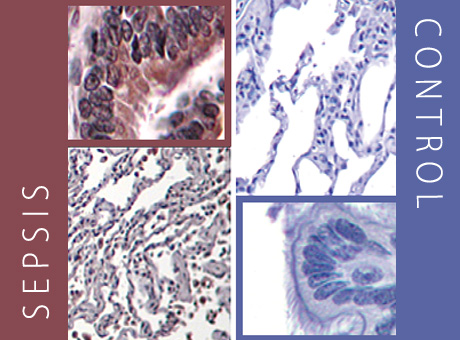

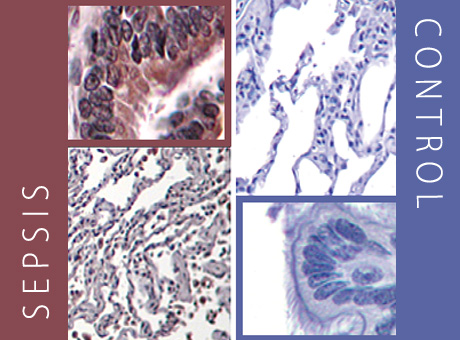

In a sepsis patient’s lung cells (left), brown indicates a protein with the potential to “turn off” T-cells. Lung cells from a patient without sepsis remain blue (right), indicating that the protein is not present.

In a sepsis patient’s lung cells (left), brown indicates a protein with the potential to “turn off” T-cells. Lung cells from a patient without sepsis remain blue (right), indicating that the protein is not present.

Patients who die from sepsis are likely to have had suppressed immune systems that left them unable to fight infections, researchers at the School of Medicine have shown.

The findings suggest that therapies to rev up the immune response may help save the lives of some patients with the disorder. Sepsis is a severe illness in which bacteria overwhelm the bloodstream.

The researchers compared tissue samples taken from the lungs and spleens of 40 patients who had died of sepsis to those of patients who died from other causes. They reported their findings in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“More than 225,000 people die each year from sepsis, and developing more effective therapies has been challenging,” says senior investigator Richard S. Hotchkiss, MD, professor of anesthesiology. “This project attempted to understand the mechanisms that underlie how the immune system responds to sepsis.”

That’s been an important question, because the onset of sepsis usually includes what doctors call a “cytokine storm,” when the body’s immune system produces a massive inflammatory response. Some patients die during this initial phase. But others survive, including a significant number whose sepsis evolves into a longer, chronic phase.

“These patients often get new infections,” says co-investigator Jonathan M. Green, MD, professor of medicine and of pathology and immunology. “They come into the ICU very sick, and we try to get them over that hump, but then they get stuck and don’t get better. They typically develop new infections, either a bloodstream infection or pneumonia.”

Hotchkiss had been collecting tissue samples from patients who died from sepsis, and Green brought expertise in lung function and immunology to the project.

First author Jonathan S. Boomer, PhD, analyzed the tissue to determine whether key immune system cells, called T-cells, were activated to respond to secondary infections like pneumonia or whether those cells were defective.

“We found that these T-cells were not able to function in the ways required to fight an infection,” says Boomer, a research instructor in medicine. “T-cells were present in both the lung and the spleen, but they failed to mount an effective immune response.”

According to Hotchkiss, the study points to how the paradigm for treating sepsis should change. “It’s pretty clear from this study that in some patients, we need to find ways to activate T-cells to fight sepsis.”