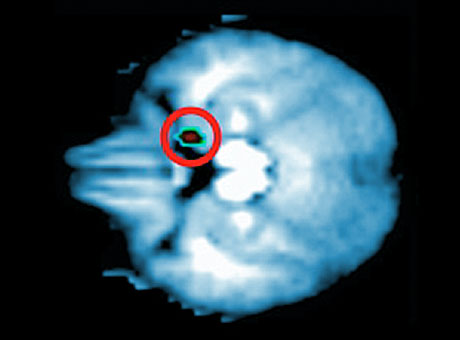

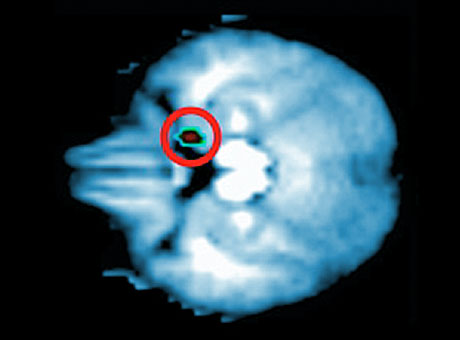

Brain scans of preschoolers with depression revealed elevated activity in the amygdala.

Brain scans of preschoolers with depression revealed elevated activity in the amygdala.

A key brain structure that regulates emotions works differently in preschoolers with depression compared with their healthy peers, new research at the School of Medicine shows.

The differences, measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), provide the earliest evidence yet of changes in brain function in young children with depression. The researchers say the findings could lead to ways to identify and treat depressed children earlier in the course

of the illness, potentially preventing future problems.

“The findings really hammer home that these kids are suffering from a very real disorder that requires treatment,” said lead author Michael S. Gaffrey, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry. “We believe this study demonstrates that there are differences in the brains of these very young children and that they may mark the beginnings of a lifelong problem.”

The study is published in the July issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

Depressed preschoolers had elevated activity in the brain’s amygdala, an almond-shaped set of neurons important in processing emotions. Earlier imaging studies identified similar changes in the amygdala region in adults, adolescents and older children with depression, but none had looked at preschoolers.

For the new study, scientists from Washington University’s Early Emotional Development Program studied 54 children ages 4 to 6. Before the study began, 23 of them had been diagnosed with depression. The other 31 had not. None had taken antidepressant medication.

While in the fMRI, the children looked at pictures of people whose facial expressions conveyed particular emotions — happy, sad, fearful and neutral.

“The amygdala region showed elevated activity when the depressed children viewed pictures of people’s faces,” says Gaffrey. “We saw the same elevated activity, regardless of the type of faces the children were shown.”

The depressed preschoolers’ responses were somewhat different from those previously seen in adults, where the amygdala responds more to negative expressions of emotion.