By Jim Goodwin

CancerVISION

Ability to see glowing cancer cells opens doors to precision treatments

CANCER CELLS ARE NOTORIOUSLY DIFFICULT TO SEE, even under high magnification. Until now, it’s been nearly impossible for operating surgeons — using only static MRIs and X-rays as a guide — to tell where the tumor ends and healthy tissue begins.

After hearing a group of doctors discuss this frustration in 2009, Samuel Achilefu, PhD, a professor of radiology at the School of Medicine, had an idea: Could night-vision goggles used by the military also work in the war against cancer?

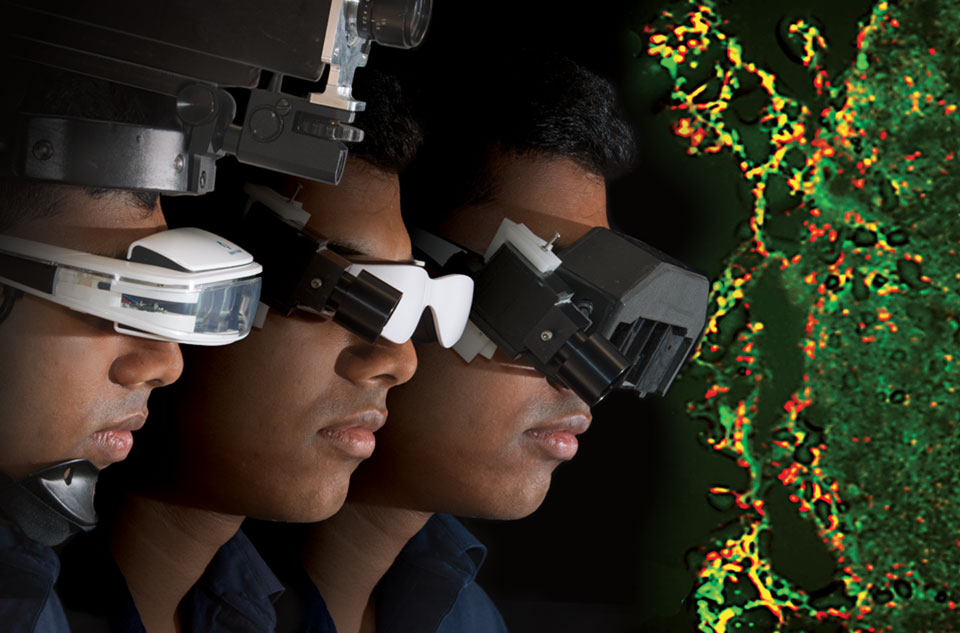

Achilefu’s mission was to design wearable technology for surgeons, helping them distinguish cancer cells from healthy cells in real time — perhaps reducing the need for additional surgeries and subsequent stress on patients.

Visionary

During a breast cancer procedure, Samuel Achilefu, PhD, tested the goggles with surgeon Julie Margenthaler, MD.

Photo by Robert Boston

To care for patients, surgeons today remove the tumor and neighboring tissue, which may or may not include cancer cells. The samples are sent to a pathology lab and viewed under a microscope. If the surrounding tissue contains cancer cells, a second surgery is performed to remove even more tissue, which also is checked for the presence of cancer. About 20 to 25 percent of breast cancer patients who have lumps removed require a second surgery. It’s a balancing act — surgeons don’t want to remove too much or too little surrounding tissue.

“No one wants unnecessary surgery — not surgeons, not nurses and certainly not patients or their families,” said Achilefu, also a professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics and biomedical engineering. “Our goal with these glasses is to eliminate follow-up surgery by removing all cancerous cells the first time.”

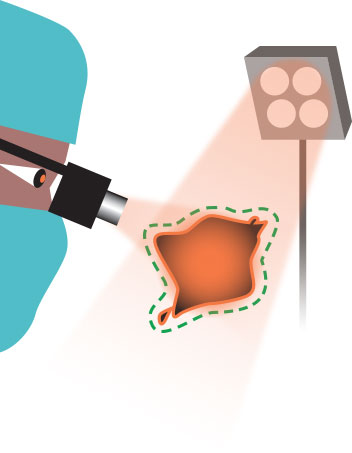

Targeting cancer

Removing a tumor and minimal surrounding tissue is rarely straightforward; typically the exact boundaries are unclear.

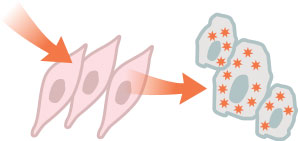

Researchers have developed dye agents that can pass through healthy cells but remain trapped within cancer cells.

As the dye fluoresces in infrared energy, the goggles aid in seeing the boundary between tumor and healthy tissue.

Technology Unveiled

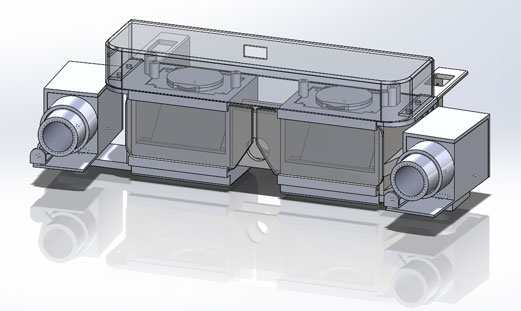

Achilefu dedicated five years to the project. Initially, people were skeptical that his idea could be realized. He carried out his research using discretionary funds from the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology and support from the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program. Achilefu assembled a multidisciplinary team, including engineers and video game specialists, who worked together to further refine and miniaturize the glasses. Over time, Achilefu successfully demonstrated the technology in mice, rats and rabbits, and, in 2012, the team received a $2.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

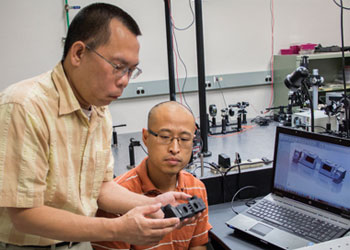

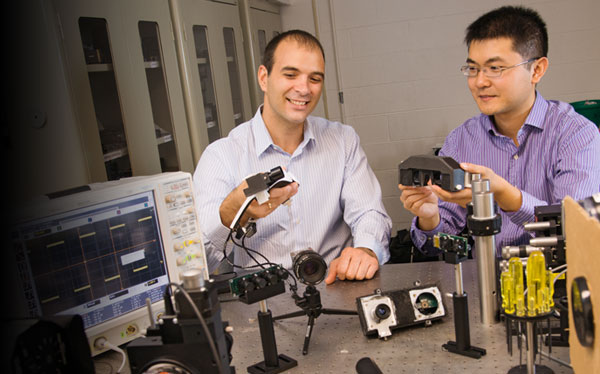

Major collaborators include Viktor Gruev, PhD, associate professor of computer science and engineering, and Ron Liang, PhD, associate professor of optical sciences at the University of Arizona (UA). Washington University graduate students Suman Mondal, Shengkui Gao and Yang Liu and UA postdoctoral fellow Nan Zhu also played key roles.

On Feb. 10, 2014, the high-tech glasses were used during surgery for the first time at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. Surgeon Julie Margenthaler, MD, operated on 67-year-old breast cancer patient Karen Clodfelter.

In this procedure, an FDA-approved, commonly used contrast agent, indocyanine green, was injected into the patient’s tumor. When viewed with near-infrared light, the cancerous cells glowed blue. Lighter shades of blue indicated higher concentrations of cancer cells.

Margenthaler was heartened by the technology, which enabled her to see the tumor, as well as the bordering malignant cells. (Tumors generally do not form in perfect circles, but instead have tentacles that branch out in different directions.)

“We’re certainly encouraged by the potential benefits for patients,” said Margenthaler, an associate professor of surgery at the School of Medicine. “Imagine what it would mean if these glasses eliminated the need for follow-up surgery and the associated pain, inconvenience and anxiety.”

So far the technology only has been used on patients with breast or skin cancer. Given the success of the initial nine surgeries — four breast and five melanoma — more are planned.

“The distinction between normal and cancerous tissue is not always clear to the naked eye,” said melanoma surgeon Ryan Fields, MD, a Washington University assistant professor of surgery who also has used the goggles. “Often, we’re relying on how something looks or feels. Even CT scans and MRI images can fail to detect microscopic cancer.”

In a study published in the Journal of Biomedical Optics, researchers noted that tumors as small as 1 mm in diameter (the thickness of about 10 sheets of paper) can be detected.

Theoretically, the technology could be used to visualize any type of cancer in the operating room.

Video components in the glasses allow surgeries to be recorded. As only a small number of observing medical students can fit into an operating room, the recordings could serve as a useful teaching tool in a larger auditorium. There also may be applications that could help guide physicians practicing in remote areas.

Achilefu has worked with Washington University’s Office of Technology Management and has a patent pending for the technology.

Could such technology curtail the need for

follow-up surgeries?

The most recent prototype would give a surgeon the best of both worlds: A clear view of the surgical field merged with an enhanced image of the glowing cancer cells.

Revolutionizing Treatment

Achilefu, who also is co-leader of the Oncologic Imaging Program at Siteman Cancer Center, is seeking FDA approval for a markedly improved contrast agent, LS301, he is helping develop.

This agent, injected into the bloodstream, selectively enters cancer cells anywhere in the body and stays there longer, up to a week, in some cases.

It appears to be the first contrast agent to mark cancer cells universally — breast, prostate, liver, brain, colon, leukemia and lymphoid cancers, even metastatic cells. The cells glow under infrared light.

Achilefu is optimistic — pending FDA approval for a pilot study — that human clinical trials will begin soon. For now, his research group — partnering in a study with the University of Missouri School of Veterinary Medicine — will be removing cancerous tumors in dogs, providing treatment hope for the pets’ owners.

If approved for use in humans, this targeted agent potentially could someday act not only as a marker, but also as a way to deliver drugs directly to cancer cells, sparing healthy tissue and eliminating some surgeries. The agent also may shed light on how tumors are responding to chemotherapy.

Another mission is born.

“Our goal is to make sure no cancer is left behind,” Achilefu said.