Accelerating the critical countdown, expediting response and treatment

By Deb Parker

Physicians today know that time makes all the difference when it comes to stroke.

The brain is unforgiving to lack of oxygen. Without it, 1.9 million brain cells die every minute. But with prompt treatment, significant disability can be minimized. Hence, “time is brain” now is a nationally recognized stroke awareness campaign.

Leading School of Medicine specialists have worked vigilantly to beat the clock. As a result, patients seen at the Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Stroke & Cerebrovascular Center have improved outcomes and are given the best chance for survival and recovery.

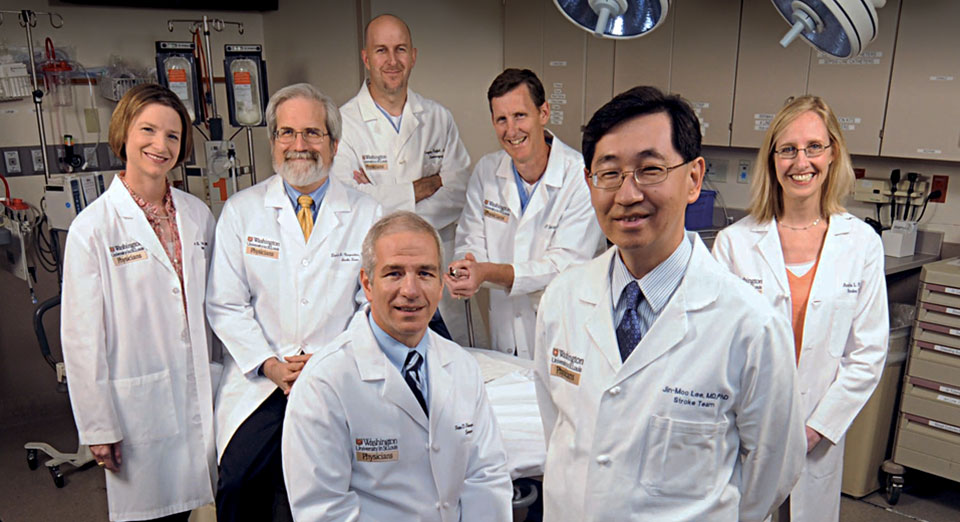

The multidisciplinary team provides some of the fastest stroke critical care in the U.S. — assembling in the Emergency Department within minutes and bringing deep resources to the high-stakes task of stroke diagnosis and treatment.

Further, School of Medicine physicians are helping to shape treatment regionally and nationally as they define and propose time-critical standards and continue to pioneer methods of evaluating and managing stroke.

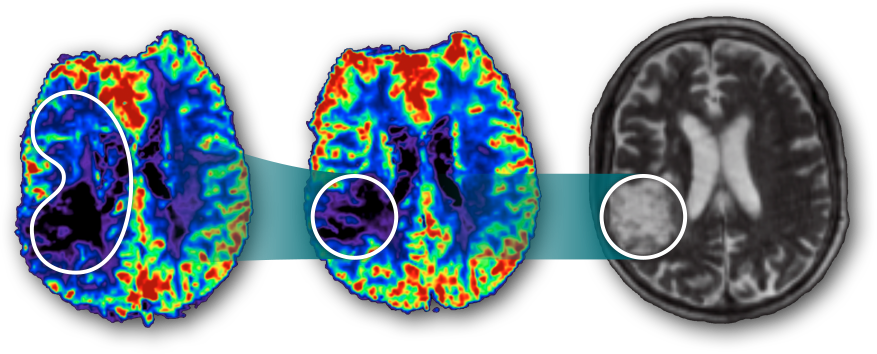

Some brain regions (red) already are irreversibly lost.

More time elapses, more brain tissue dies. Urgent treatment could still limit the disability.

The window is closing. Treatment at this time may result in moderate disability.

Without treatment, all at-risk tissue has died; the unfortunate result may be severe disability.

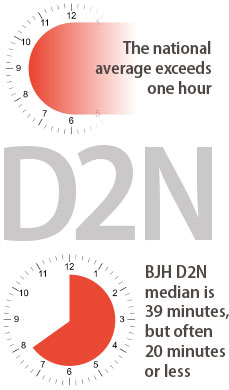

Decreasing door-to-needle times

Washington University physicians at Barnes-Jewish treat 1,600 strokes annually, with four to 10 suspected stroke patients arriving each day. Despite these high volumes, the stroke center has achieved one of the fastest “door-to-needle” averages in the country.

“Door to needle” (D2N) is the time between the patient’s arrival at the hospital and IV administration of the clot-dissolving drug tPA (tissue-plasminogen activator). The drug widely is considered the best course of action in an ischemic stroke, when a clot cuts off blood flow to parts of the brain.

Ideally, the drug should be delivered within 60 minutes of stroke onset, the so-called “golden hour.” If tPA is given within three hours of an ischemic stroke, one in three patients will benefit and, within 4.5 hours, one in six patients will benefit.

A patient’s maximum deficit, such as paralysis on one side of the body or slurred speech, happens at the time of stroke onset when a brain region is starved for oxygen. If blood is restored quickly, these effects essentially can be undone.

The longer it takes to administer treatment, the more likely the patient will suffer permanent consequences.

Nationally, the average D2N time is as high as 80 minutes, according to the American Stroke Association. Today, the D2N median at Barnes-Jewish Hospital is 39 minutes, with many patients receiving tPA in 20 minutes or less. The next goal is to sustain a 30-minute median.

Transforming a complex process

How does a broadscale team — involving emergency medicine physicians, neurologists, neurosurgeons, radiologists, interventional neuroradiologists and dozens of ancillary staff — become that nimble?

In 2010, the median D2N time in the Barnes-Jewish Emergency Department (ED) was 55 to 60 minutes, but the stroke team determined it could do better by applying lean manufacturing principles developed by the Japanese car manufacturer Toyota.

Team members met for two days with lean engineers to examine each of the 50-plus steps leading to tPA administration. Each step — from patient registration and vital signs monitoring to labs and imaging — was evaluated from an efficiency perspective. The objective was to reduce bottlenecks, improve teamwork and communication and ensure that those caring for patients have easy access to supplies and equipment.

“We sought suggestions from everyone involved, from the paramedics who bring in patients, to admitting clerks, radiology technologists, nurses and physicians,” said Jin-Moo Lee, MD, PhD, senior author of the study that was published in Stroke. Lee is a Washington University neurologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and director of the Department of Neurology’s cerebrovascular disease section.

The complex treatment process could be streamlined, they decided — even before patients arrive at the hospital.

Activating the stroke team en route

In the past, emergency medical services (EMS) personnel brought the patient to Barnes-Jewish Hospital and clinicians there determined whether the person was having a stroke.

Paramedics now alert Barnes-Jewish Hospital staff when a potential stroke patient is en route. An immediate page goes out to stroke team members who are ready and waiting when the ambulance or helicopter arrives. EMS partners are well trained and fully entrusted to activate the team. “One thing we’ve learned is that you have to cast a very wide net,” Lee said. “We have a very liberal policy for stroke pager activation. For every eight activations, only one is treated with tPA. It’s a lesson to learn: capture as many as you can and consider all potential candidates.”

Using clinical scales, EMS workers can determine the severity of a stroke. They also can lower a patient’s high blood pressure en route, making tPA treatment a more viable option.

And to help determine time of stroke onset, which is critical when evaluating treatment options, EMS crews will begin a new practice: leaving calling cards with witnesses, encouraging them to contact the stroke team with more details.

Brain cells need constant nourishment to survive; it’s delivered by blood via the arteries. When blood flow is disrupted — due to a blockage (ischemic) or a ruptured artery (hemorrhagic) — myriad cells begin dying, short-circuiting vital functions. Soon, the person may no longer be able to see, speak or function in familiar ways.

Seconds count— from the moment of stroke onset, to the arrival of emergency personnel, through transport to a hospital. Expertise, equipment and enhanced protocols make a certified stroke center the destination of choice, even at a farther distance. However, when patients cannot make the journey, Washington University stroke physicians partner with community hospitals in critical care decisions, using telemedicine.

Stroke teams seek to compress the time until treatment begins. Parallel processing — in which team members work simultaneously to perform a variety of tasks — facilitates this race against the clock. Innovative approaches to practical problems help deliver treatment in 30 minutes or less in some cases.

Working in concert

Previously, suspected stroke patients first were taken to a trauma bay for history taking, blood draw and neurological exam. From there, they were transported to an ED-dedicated CT scanner to determine whether the stroke was ischemic or hemorrhagic (ruptured artery), before being taken back to the trauma bay for further assessment.

Based on recommendations of the process improvement team, paramedics now sidestep the trauma bay and take the patient directly to the CT scanner for prompt evaluation.

“We can obtain the story, begin the neurological exam, initiate patient registration, complete the brain imaging within minutes — all in the CT scanner room — quickly determining if the patient meets tPA criteria,” said Peter D. Panagos, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine and neurology. “Eliminating these extra steps saves 12 to 15 minutes.”

Using parallel processing, steps previously performed in sequence are carried out simultaneously with additional staff. Every team member has a role that is not duplicated. Instituting lab tests that could be performed at the bedside reduced time spent waiting for results.

Meanwhile, interventional radiologists are on standby for patients who do not respond to tPA. These patients may benefit from endovascular interventions using tools that can retrieve clots or open arteries in other ways. In the past few years, these devices have shown great improvement, according to Colin P. Derdeyn, MD, professor of radiology and director of the stroke and cerebrovascular center.

Acute stroke team members converge at the CT scanner upon patient arrival; ED nurses respond with carefully choreographed, pre-planned routines.

Emergency medical transport leader conveys patient information to stroke team physicians; physicians perform rapid neurological tests, assessing lab results and responding with real-time decisions.

Patient is stabilized and ready for a brain scan and its immediate review by physicians. Intravenous drip is in place and ready to administer therapeutic drug.

Improving patient outcomes

Following months of refinement, 78 percent of patients now are treated within “the golden hour” — up from 52 percent — and team members continue to speed the process.

“This is only one of our lean process success stories,” Lee said, “but it nicely demonstrates how lean transformation can improve processes across the spectrum of stroke care.”

After the patient is admitted to the hospital, the team puts much of its emphasis on preventing life-threatening complications and determining why the stroke occurred in the first place, taking steps to prevent the high risk of recurrence. For instance, as atrial fibrillation is a common stroke trigger, the patient may be placed on an anticoagulant.

Striving toward personalized care

Remarkably, School of Medicine researchers are beginning to suggest that some of those patients who miss the optimal three-hour treatment window may still have hope. In limited cases, physicians here are, in effect, throwing out the clock.

“Every stroke case is different,” Lee said. “Some patients may have just enough blood flow to preserve brain tissue — even after six hours. Other patients might not have viable brain tissue after one hour.” Future technologies may provide a more sophisticated determinant.

Lee is leading a study searching for new methods to image and identify salvageable tissue.

Oxygen metabolism is a good indicator of brain viability. Lee and Andria Ford, MD, assistant professor of neurology, devised a quantitative map of oxygen metabolic index (OMI) viewable on MR scans. As OMI drops, there is a threshold at which brain cells will stop working but may still be alive, and another threshold past which tissue is dead. This initiative is based on the theoretical work of radiology professor Dmitriy Yablonskiy, PhD, and performed in close collaboration with Weili Lin, PhD, and Hongyu An, DSc, at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Initial results suggest this six-minute scan accurately highlights brain areas that may survive if successfully reperfused. Knowing this would allow stroke teams to more effectively determine the appropriate course of action — tPA, interventional radiology — or perhaps some treatment that hasn’t yet been developed.

“It’s all about providing the right care to the right patient at the right time,” Lee said.

A massive brain region (left) starves for oxygen; restoring blood flow could prevent severe permanent disability.

A clot-busting drug therapy successfully restores oxygenated blood to all but the encircled region.

The area of permanent damage corresponds to high-risk region that was shown by the six-hour metabolism scan.

Reaching beyond the hospital

In 2013, Barnes-Jewish became the first comprehensive stroke center in Missouri and among the earliest in the country.

The Joint Commission and the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association established the advanced certification to recognize hospitals that achieve higher standards and meet criteria for resources, staff and training essential to treating the most complex stroke cases. Comprehensive stroke centers provide the full spectrum of care, from diagnosis to specialized rehabilitation. David A. Carpenter, MD, associate professor of neurology, directs Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s comprehensive stroke center.

Missouri’s Time-Critical Diagnosis statute dictates that, in the same way car crash victims must be taken to trauma centers, stroke patients now must be taken to certified stroke centers, sometimes bypassing closer hospitals. Time lost in transit might be made up with resources and expertise. Washington University faculty members were key in crafting this legislation; several sit on state review boards, traveling to various hospitals to evaluate their processes.

The team shares best practices and, through web-based communications, conducts real-time patient assessments with regional emergency departments, particularly those in rural counties that may have no immediate access to neurologists or other specialty physicians.

Some hospitals are not equipped to administer tPA or make acute-care decisions; others can administer tPA and transfer patients to comprehensive stroke centers. Because of these collaborations, some hospitals previously bypassed by paramedics now are equipped to deliver care for milder strokes, while severe strokes still are best served at comprehensive centers.

“This is about how you can impact remote communities with a collective effort,” Lee said. “This major push has made all the difference. Time-critical diagnosis has prompted us to rethink how we handle regional patient flow.”