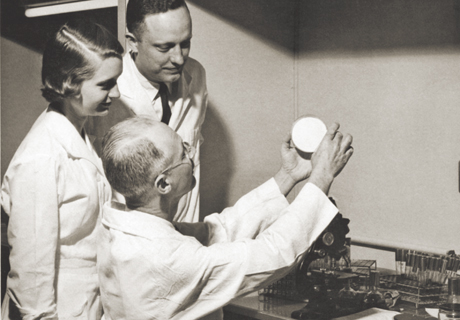

Before he was Dean: King, standing, in the late 1950's, in the bacteriology lab with Carl Harford, MD, and an unkown female colleague.

Before he was Dean: King, standing, in the late 1950's, in the bacteriology lab with Carl Harford, MD, and an unkown female colleague.

M. Kenton King, MD, acting dean of the School of Medicine, was sitting in his office early in 1965 when Carl F. Cori, MD, strode in, unannounced. Cori, a Nobel laureate and biochemistry department chairman, was a giant of the medical school. Even among the members of its governing body, the Executive Faculty, he stood out as talented and strong-willed.

“Nobody would argue with Carl Cori,” says King today, chuckling. “What they would do if they disagreed with him was simply remain silent.”

On this day, Cori paced restlessly up and down and then issued a terse request from the search committee that he chaired. “We have decided we want you to be the dean. Will you accept?” In case King felt any qualms about the workload or about succeeding Edward Dempsey, MD, who had left abruptly after a contentious tenure, Cori added some reassurance: “You’ll only need to be in the office 30 minutes a day.”

So the 39-year-old King — until a few months earlier an associate dean and internist, with only hazy administrative ambitions — took on this huge, complex and decidedly full-time task. When he retired in 1989, after 25 years of service, he had become one of the longest-serving medical deans in the United States, as well as one of the most successful.

Academic hero

“Ken King is one of my heroes,” says Larry J. Shapiro, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs and dean of the medical school. “In his quiet and unassuming way, he played a key role in shaping the current Washington University School of Medicine. He led with integrity and had the respect and confidence of faculty, students and staff. He has served the School long and well and has left an enduring mark.”

A quiet leader: M. Kenton King says that he "just wanted to do a good job."

Letters from colleagues, written at the time of King’s retirement, speak eloquently to his decency and fair-mindedness, kindness and wisdom, patience and honesty. “You have the wonderful ability to recognize foibles and defects in people without becoming cynical or disdainful about them,” wrote Samuel B. Guze, MD, chairman of the Department of Psychiatry. “As you know, I believe you would have made a superb psychiatrist.”

Said Harvey R. Colten, MD, chairman of the Department of Pediatrics: “Casey Stengel said, ‘The secret of managing a ball club is to keep the five guys who hate you away from the five who are undecided.’ You would have done this but for you, in a sense, the task has been easier. Who could ever find the five guys who hate you?”

Or as neurology head William M. Landau, MD, wrote: “Whatever has been accomplished in this department or this medical school in the last quarter century includes more than a fair share of Ken King’s blood, sweat and tears. Your quiet leadership has launched us into our world-class role.... “I am glad that you will hang around to remind our successors from time to time that consistently thoughtful consideration works miracles.”

Childhood and education

Born and raised in Oklahoma City, M. Kenton King (M for “Morris”) was the son of C. Willard King (C for “Cassius”), a dry goods salesman from a tiny Kansas town where it was the custom to give children an honorary first name. No one in King’s family was a doctor, but after serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II and graduating from the University of Oklahoma in 1947, he decided to attend Vanderbilt University’s medical school on the G.I. bill.

By the time he had finished, he was seventh in his class. “Many medical students were married and a few had children,” he says with self-deprecating humor. “I had nothing else to do at night but study.”

For his internship, he was accepted into the demanding program at Barnes Hospital, and then stayed for residency training in internal medicine, serving as chief resident in 1955. Among this faculty of outstanding physicians, he most admired internal medicine head W. Barry Wood, MD, a star scholar and athlete. When Wood left for Johns Hopkins University in 1955, King went along to do a fellowship in microbiology and become a junior faculty member.

In 1957, he returned to Washington University to join the preventive medicine faculty and head the Student Health Service, becoming associate dean five years later. By then he had a wife — June Greenfield King, a 1951 graduate of the Washington University School of Nursing and formerly head nurse on a Barnes Hospital medical and surgical ward — along with a growing family. Asked in 1965 about his hobbies, he said: “I’ve got four boys at home. All are under seven years old. Need I say more?” Their workload increased when a fifth son was born the following year.

Highlights of the King years

With his surprise accession to the deanship, he began work on several fronts. Early on, he made a key appointment, naming pediatrician John C. Herweg, MD, as associate dean of the medical school with responsibility for admissions. “I thought that was one of the best decisions I ever made,” he says now.

As vacancies occurred, he chaired committees that eventually recruited new heads in all 17 departments, thus reshaping the Executive Faculty. Among the external choices he names with great satisfaction are P. Roy Vagelos, MD, replacing Cori in biochemistry, Philip R. Dodge, MD, in pediatrics, and Gerald D. Fischbach, MD, in anatomy.

At the same time, he championed a dramatic change in the composition of the student body, favoring more minority and women students. In 1964 he told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: “There is simply no basis for skepticism about women doctors any more....[W]omen have distinguished themselves beyond doubt in every field and function of medicine.”

By the end of his tenure, the campus looked vastly different, with more than 30 buildings spread over 50 acres. Among the additions were the McDonnell Medical Sciences Building, the Clinical Sciences Research Building, a renovated East Building and the new Becker Medical Library. In other areas, King worked to strengthen the amount and quality of medical research and to bolster alumni relations.

Today, he remains keenly interested in the School’s welfare, while enjoying his family, which now includes eight grandchildren. Last October, he and his wife faced a tragic loss when their son, University City Police Sgt. Michael King, AB ’80, was killed while on duty in the Delmar Loop.

Reflecting on his tenure, King is characteristically modest. “Many of the deans in the country were chosen for some other feature, such as their research,” he says. “I had an attitude that some of the other deans did not possess: that is, I just wanted to do a good job as dean.”

And while he might never admit it, he succeeded. His successor as dean, William A. Peck, MD, wrote in his laudatory 1989 retirement letter: “You have established a new benchmark for dedication to our institution.” Or as William H. Danforth, who served alongside King as medical school vice chancellor before becoming university chancellor, put it in his 1989 retirement letter: “The King quarter-century has been a golden age. It has been an honor to have been a part of it.”