Living with a challenging

condition: Kevin Baffa

INTERACTIVE

Understanding how Barth syndrome affects the body VIEW >

BY BETH MILLER

Easy-going, witty and bright, Kevin Baffa is unruffled when describing how he coped with his first cardiac arrest at age 11 and two more over the next eight years.

The 22-year-old has Barth syndrome, a rare genetic disorder of fat metabolism that occurs only in males. It’s so rare — diagnosed in fewer than 200 boys and young men worldwide — that many physicians are unfamiliar with it. The syndrome, caused by a gene defect, results in impaired heart function, muscle weakness and exercise intolerance.

Although Barth syndrome occurs only in males, it is passed down from the mother. In addition to its effects on the heart, it causes neutropenia, or very low numbers of white blood cells, which help to stave off infection. There is no specific treatment for Barth syndrome, though some heart drugs and dietary supplements have been used with some success. Many patients have intracardiac defibrillators implanted to sense their cardiac rhythms and sometimes pace the heart. Severe infections and heart failure are common causes of death.

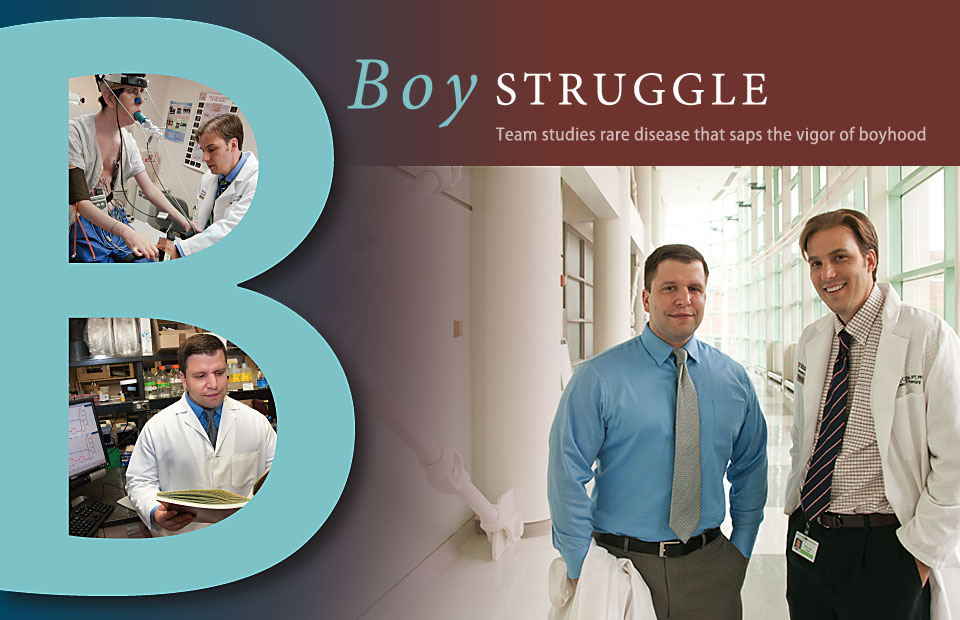

Although this is a rare disease, Washington University School of Medicine has two researchers who are devoted to finding a cause and effective treatments.

W. Todd Cade, PT, PhD, assistant professor of physical therapy and of medicine, is studying the impact of exercise on heart function and exercise tolerance in patients with Barth syndrome. He already has completed a pilot study looking at nutrient metabolism in these patients and is now seeking federal funding to continue the study.

Michael A. Kiebish, PhD, a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of Medicine’s Division of Bioorganic Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, is one of only a handful of researchers worldwide working with an animal model of Barth syndrome. The Barth Syndrome Foundation has funded all three projects.

Baffa’s journey began when he had congestive heart failure at 10 weeks old and was put on life support. As he got older, he had other health and development issues. Seven years passed before the Baffa family found a neurologist who diagnosed Barth syndrome. Still, there was little information available about the disorder.

Baffa’s mother, Rosemary, eventually connected with another family struggling to understand the disorder. That contact was the beginning of what is now the Barth Syndrome Foundation, a community of families, physicians, scientists, donors and volunteers that works to find the cause and treatment for this mysterious metabolic disorder.

Cade’s research with Barth syndrome patients began after a serendipitous 2006 meeting with Barry J. Byrne, MD, PhD, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Florida. Byrne learned of Cade’s research related to exercise and metabolism in patients with HIV and invited him to the International Barth Syndrome Conference to collaborate on an exercise study.

“Before then, I had never heard of Barth syndrome,” Cade says. “Because it is a relatively newly diagnosed disease, there is still much to learn regarding its pathophysiology and relation to impaired skeletal muscle and heart function.”

After getting to know the patients and their families at the conference, Cade expanded his research to include Barth syndrome. Parents of boys with Barth syndrome often keep their sons from exercising due to their impaired hearts, increased risk for abnormal heart rhythms, fatigue and muscle weakness. But Cade says this lack of aerobic exercise may be having an even more negative effect on the body.

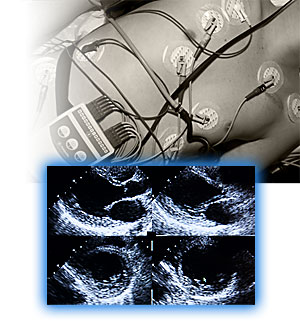

To test his theory, Cade launched a pilot study in July 2010 at the Barth Syndrome Foundation’s biennial international conference. Five young men with the syndrome, including Baffa, took a stress test on a stationary bicycle to measure peak oxygen consumption (VO2), a test of heart function, and a test of the ability of leg muscles to extract and use oxygen during exercise.

Cade then designed exercise programs for the study participants, who completed a progressive aerobic workout on a stationary bike three times a week at a hospital-based physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation clinic in their hometowns. The clinics reported each patient’s data to Cade, who also kept in touch with the study participants.

As the study period ends, Cade is retesting each patient at the School of Medicine looking for improvements in heart function, VO2, exercise tolerance, leg muscle oxygen extraction and quality of life. His assessment team includes Washington University cardiologists, EKG technicians and physical therapists, and Sara Seyhan, a clinical specialist from CAS Medical Systems Inc., who performs the leg-oxygen-extraction measurements. CAS is donating Seyhan’s service and equipment to the project.

Baffa came to Washington University Medical Center in March for his end-of-study testing. Before joining Cade’s study, he wasn’t exercising at all, so initially it was tough.

“Once I started exercising more frequently, I did get stronger,” he says. “I went from five minutes on the bike in my first session to 45 minutes straight in my last session.”

Baffa’s results were promising: His exercise time increased by 13 percent; peak oxygen consumption by 11 percent.

Still, the exact cause of Barth syndrome remains elusive.

Cade and Kiebish have discovered that nutrient metabolism abnormalities may play a role. Metabolism involves a complex process in the mitochondria of cells known as the TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle, which breaks down carbohydrates, proteins and fats into energy. But in boys with Barth syndrome, something is going wrong.

A boy’s heart function is monitored during a test in the clinic.

“Results from our clinical study show that amino acid metabolism is dysregulated in this group; we think this is because mitochondria in the boys’ cells can’t effectively use fatty acids at rest,” Cade says. “Instead, we believe the mitochondria take amino acids from the muscle and heart for energy.”

Kiebish adds that boys with Barth syndrome do not metabolize amino acids, fatty acids and glucose correctly because mutations in the tafazzin (TAZ) gene decrease the remodeling of cardiolipin, a lipid that regulates energy metabolism in mitochondria.

“The heart usually burns fatty acids for energy, but in Barth syndrome it can’t, because the TCA cycle is out of sync and is going after amino acids instead,” he says. So the heart doesn’t develop properly because it is deprived of energy.”

Kiebish studies cardiolipin and the TCA cycle in the Barth syndrome mouse model. By administering doxycycline, a common antibiotic that stops production of the TAZ gene, he is able to replicate the defective metabolic processes that occur in Barth syndrome.

“I’m able to take my findings from the lab and tell Todd what is probably happening in the boys and what we should be looking for,” Kiebish says.

Although both researchers have only been involved with these patients for a few years, their dedication is evident.

“We put Barth syndrome up front because it’s worth it,” says Kiebish. “Every inch forward makes miles of difference.”

in the lab.