Imagine being a child in 1930s Germany, called into a room where a man in a white coat holds up charts next to your face to look at your eye color and uses tools to measure the bridge of your nose, width of your forehead and circumference of your head.

Hundreds of thousands of children and adults were measured this way by physicians, who also recorded family genealogies to trace hereditary traits. The practice was part of a broad effort using German physicians and others to racially “cleanse” European society of people seen as biologically inferior and those perceived as racial enemies of the German people.

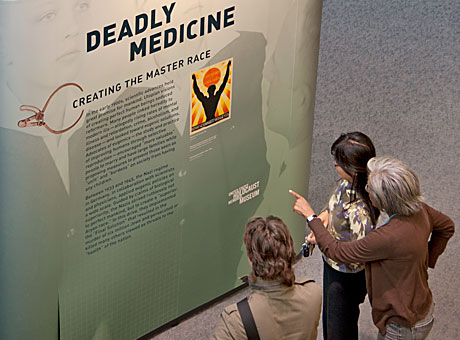

This practice of the “science” of eugenics, or racial hygiene, as it was known in Germany, is featured in “Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race,” a traveling exhibition from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum recently on display at the School of Medicine’s Bernard Becker Medical Library. The exhibit highlights the role of science and medicine in the Holocaust.

In the 1930s, the National Socialist (Nazi) party enacted a law preventing “genetically diseased offspring” by a mass sterilization program. This emulated sterilization laws enacted decades earlier in the United States and the Scandinavian countries. More than 400,000 German citizens were sterilized over the next 13 years for hereditary conditions including schizophrenia, manic-depressive disorder, genetic epilepsy, genetic blindness or deafness, and severe physical deformity, among others.

Midwives and physicians were enlisted to register all children born with severe birth defects and, during World War II, the program was expanded to include children and adults deemed “incurable.” They were sent to specialized hospital centers, where they were then gassed or starved to death. The Nazis justified these as “mercy deaths,” using asylum directors, physicians and nurses to end “lives unworthy of life” for the good of the Fatherland.

In 1942, the “euthanasia” program and its medical personnel were moved to German-occupied Poland. There, in camps specially constructed as killing centers, gas chambers were used to murder millions. It was to these death camps that 6 million Jews and hundreds of thousands of Romany were transported from throughout Europe and killed in a policy of total extermination (“the final solution”).

"'Deadly Medicine' helps us understand how our contemporary world came to be and the human stakes involved in trying to improve the human race."

—Stephen S. Lefrak, MD

“‘Deadly Medicine’ helps us understand how our contemporary world came to be and the human stakes involved in trying to improve the human race,” says Stephen S. Lefrak, MD, professor of medicine and assistant dean of the Program for the Humanities in Medicine. “If history teaches us anything, it is that what has happened, can in fact happen. It certainly behooves an engaged citizen to comprehend that National Socialist Germany was a biological state that sought humankind’s perfection through racial and biological selection. Therefore, for medicine in the age of genomics, in vitro fertilization and the search for wonder cures, the exhibit is a striking billboard warning us to be wary of the promise of biological utopian fantasies.”

Robert W. Sussman, PhD, professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, says the exhibit presents many historical events and ideas that aren’t commonly known.

“In many cases, people don’t realize how medicine and science can be used in such a very bad way,” Sussman says. “People have forgotten how horrible those things that occurred during World War II were. The ‘Deadly Medicine’ exhibit shows very well the connection between medical scientists and anthropologists and how the American eugenics movement influenced the Nazis.”

Sussman says many of the ideas presented in the exhibit about different races are still an undercurrent in the United States today.

“This exhibit really shows how people can think so differently, how the behaviors we think are atrocious can be really part of their culture.”