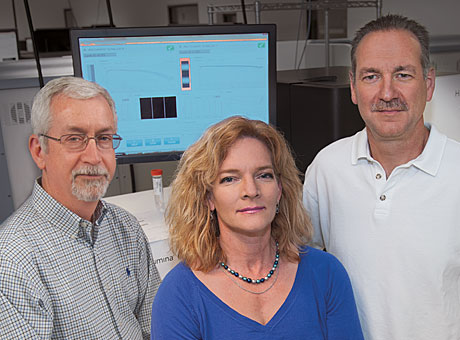

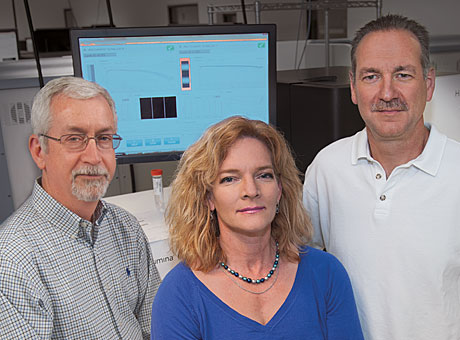

Timothy J. Ley, MD, left, Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, and Richard K. Wilson, PhD, use genome sequencing to understand the roots of cancer.

Timothy J. Ley, MD, left, Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, and Richard K. Wilson, PhD, use genome sequencing to understand the roots of cancer.

As genomic discovery research finds more genes that are commonly altered, leading to various types of cancer, treatment will focus not only on the body part being treated — breast, colon or prostate, for example — but also on the genetic blueprint of the disease.

“Precision cancer medicine will mean that therapeutic decisions are based on the underlying mutations in each patient’s tumor,” says Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, co-director of The Genome Institute at Washington University.

More than 10 years ago, Institute scientists played a leading role in an international effort, the Human Genome Project, that decoded the complete sequence of human DNA. Today, the Institute is one of only three U.S. large-scale genomic centers funded by the National Institutes of Health.

In the fight against cancer, research at the Institute has breathtaking consequences. In 2008, a team of researchers led by Timothy J. Ley, MD, the Lewis T. and Rosalind B. Apple Professor of Oncology, was the first to sequence the entire genome of a cancer patient, a woman diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), thanks to a generous gift from Alvin J. Siteman. By comparing her cancer genome to similar data obtained by sequencing the patient’s healthy cells, the team identified 10 mutated genes, setting the stage for using next-generation sequencing and analysis to decode hundreds of cancer cases.

Now, Institute researchers have completely sequenced the DNA from paired tumor cells and healthy cells of more than 1,000 patients, effectively transforming the field of cancer genomics. The resulting data has had profound consequences for understanding the genetic basis of cancer, has identified key genes related to predicting outcome in several cancer types and has helped researchers consider how to make cancer therapy choices more precise, based on the mutations underlying individual tumors.

Researchers say more funding could speed up whole genome sequencing for oncology. Six years ago, sequencing the whole genome of the AML patient took eight months. Today, it takes 28 hours. “I envision going from completing whole genome sequencing for 12 patients a year to hundreds of patients a day,” says Institute director Richard K. Wilson, PhD. “We need to make this process more efficient; you can’t do precision medicine without the basic genome work happening first.”