Partnership envisions novel treatments for mental illness

Psychiatric disorders affect more than 80 million Americans, disrupting their ability to cope with daily living. Left untreated, the individual and societal costs are staggering — including disability, unemployment, substance abuse, physical illnesses, family discord, homelessness, incarceration and suicide.

Despite the prevalence of psychiatric problems, there are relatively few effective drugs for treating them. Even the best drugs are limited, treating a portion of a person’s symptoms, and many cause side effects. Novel pharmacological targets remain the best hope for diminishing the major public health impact of psychiatric illnesses, but drug makers have largely abandoned the effort following failed clinical trials. Development, they have determined, is too risky and expensive.

Current antidepressants, antipsychotics and anti-anxiety drugs remain largely unchanged from past decades. Newer modifications might be safer or more tolerable, but a truly innovative drug hasn’t been discovered for 30 years.

“Most of the drugs used today focus on the same molecular targets in the brain as drugs that were used in the 1950s and ’60s,” said Charles Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor of Psychiatry and Neurobiology and head of the Department of Psychiatry.

Modifying neural circuits is key

A new day may be dawning. Thanks to a visionary $20-million gift from Andy and Barbara Taylor and the Crawford Taylor Foundation, the School of Medicine now is home to the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research. Established in fall 2012, the institute seeks to advance the science underlying the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric illnesses.

Historically, the School of Medicine has led the field of biological psychiatry and was among the earliest to define mental illness as a disease, not a character flaw — one that could be investigated in the same way as cancer or heart disease.

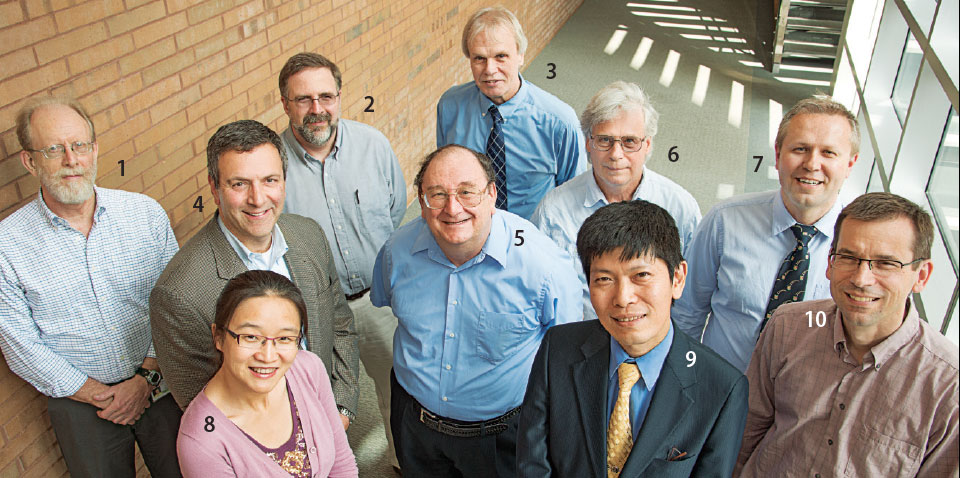

The institute unites basic and clinical researchers from several medical school departments. Together, the investigators bring complementary skills and interests ranging from medicinal chemistry to animal behavior.

“Our main objective is to find new treatment targets in hopes of developing more effective drugs,” said Zorumski, the institute’s director.

Scientists do not yet understand the mechanisms causing psychiatric illnesses, but Zorumski said it is clear they cannot be explained solely as chemical imbalances, as once was thought. “Neurochemistry may be involved, but there are many pathways to explore,” he said.

Psychiatric drugs today often treat symptoms. Instead, the institute is looking at new therapies to alter the brain networks, or circuitry, associated with psychiatric disorders. It’s these networks that are involved in the symptoms of the illnesses.

“Our current view is that major psychiatric illnesses reflect dysfunction in the brain networks that underlie cognition, emotion and motivation,” Zorumski said.

Specifically, cognition refers to how people think, perceive and remember. Emotion is how people attach meaning, and motivation is how people set and work toward goals. These processes, which work through various neural pathways that have yet to be fully understood, often are impaired in mental illness. “The key is to find treatments (pharmacological and psychotherapeutic) that modify dysfunctional neural circuits,” he said.

Targeting naturally occurring chemicals

There is shared circuitry among psychiatric disorders, although specific illnesses may involve different parts of this circuitry. For example, changes in the hippocampus, a brain region involved in memory processing, occur in schizophrenia, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Yet, how this region is involved may differ among the disorders.

Schizophrenia, for instance, signals a breakdown in thinking and poor emotional responses. It involves three types of symptoms: positive, meaning additional symptoms most people do not typically experience, such as delusions and hallucinations; negative, meaning symptoms reflecting deficiencies, such as social withdrawal and an inability to express emotions; and cognitive, meaning problems with attention, language and short- and long-term memory.

Current therapies treat schizophrenia’s positive symptoms, but do virtually nothing for the negative or cognitive symptoms, which hamper one’s ability to function in a job or relationship. Thus, investigators are looking for treatments that could address these cognitive and negative symptoms.

Initial research focuses on neurosteroids and oxysterols, naturally occurring, cholesterol-derived brain chemicals that may help regulate cognition, emotion and motivation.

In a recent Journal of Neuroscience article, School of Medicine researchers explained how, in animal models, oxysterols modulate cell receptors involved in learning and memory. These receptors differ from those targeted by current medications and so they could be useful in the development of new drugs. “Whether oxysterols are involved in the biology of schizophrenia is an unanswered question,” Zorumski said. “Regardless, oxysterols may represent a new approach to improve brain function in patients with mental disorders.”

Similar considerations can be made for neurosteroids, which help control how neurons respond to stressors in the brain. By modulating function of key brain networks, neurosteroids could serve as effective treatment strategies in a variety of disorders.

Stress, the evidence shows, diminishes neurosteroid production; decreased neurosteroid levels are linked to depression, anxiety, alcoholism, epilepsy and Alzheimer’s, among other disorders.

Replacing these depleted levels with synthetic neuroactive steroids may help alleviate the altered stress responses and allow the brain to function more normally.

Researchers are working to identify neurosteroids and oxysterols in the brain, how they are made and how they bind to cell receptors. They are studying natural and synthetic versions of these molecules not only as psychiatric treatments, but also as potential anesthetics.

circuits

animal models

testing

trials

Cabinetful of possibilities

Although the Taylor Family Institute is new, decades of prior collaborations brought researchers national recognition for neurosteroid, neuronal function and anesthesia research.

“We were mostly trying to learn about the anesthetic effects,” said Douglas F. Covey, PhD. “Now, we’re also looking at how those molecules might influence psychiatric health.”

Covey, a medicinal chemist and professor of pharmacology in developmental biology, dedicates his career to identifying natural and designing synthetic neurosteroid molecules. Hexagonal drawings mark notebooks, countertops and the glass-covered hoods where the molecules are made in his lab.

Covey and his team have built a library of more than 700 compounds. Pointing to a large file cabinet, he half-kiddingly explained that the molecules documented in those drawers may be good candidates for anesthetics. It’s possible, he said, that some of the therapies being sought by Taylor Institute scientists for mental illness already exist there.

Route to clinical trials

Transforming a synthetic molecule into treatment requires significant resources. Taylor Family Institute scientists are excited about a partnership with Massachusetts-based SAGE Therapeutics, which develops medicines for central nervous system disorders. SAGE could quickly move promising therapeutic molecules into clinical trials, and already has licensed the contents of Covey’s file cabinet.

Institute scientists also are studying potential treatments developed elsewhere. “The anesthetic drug ketamine may have the potential to alleviate depression in some patients with a treatment-resistant form of the disorder,” Zorumski said. “We’re testing that now, and we will investigate other novel therapies.

“The field of psychiatry has been doing the same things over and over again with the same result. We think it’s time to try a new approach.”