During World War I, Hardesty (seated) helped several soldiers escape from a prisoner of war camp in Villingen, Germany. One of the men, Edouard Issacs (right), who changed his surname to Izac, went on to become a U.S. Congressman from California.

By all accounts, St. Louis ophthalmologist John Franklin Hardesty, MD (1887-1953), was a hero. As a member of the U.S. Army Medical Corps during World War I, he risked his life to help soldiers on the front lines. After the war, he sent assistance to Polish and Russian soldiers he met while being held as a prisoner of war in Germany. And as a physician, he helped pioneer glaucoma treatments, provided free care to those in need and advocated for laws to benefit the blind.

“When he died, so many people came to his funeral,” said Jane Hardesty Poole, AB ’61, Hardesty’s daughter. “Some of his patients were in tears because he had saved their or their child’s eyesight. My mother and I had no idea he had helped so many people.”

To honor her father’s memory and legacy of service, Poole has committed $10 million to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. In recognition, the department will be renamed the John F. Hardesty, MD, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

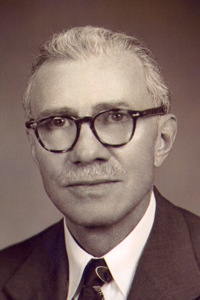

John Hardesty, MD

“Our department has a long history of advancing understanding of eye diseases and vision loss, particularly in the area of glaucoma,” said Todd Margolis, MD, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor and department chair. “It is fitting that the department now will bear the name of a man whose life’s work involved preserving vision and improving the quality of life for glaucoma patients.”

The gift will support ophthalmology research, clinical care and innovative training programs, and will help the department recruit and retain outstanding physician-scientists.

One of 12 children, Hardesty was born in Winfield, Missouri. He earned bachelor’s and medical degrees from Saint Louis University in 1914, and completed an internship and residency at St. Louis City Hospital. He had just begun to practice medicine in St. Louis when the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917.

After joining the U.S. Army Medical Corps, Hardesty was among the earliest group of surgeons to volunteer to serve with the British Army as a member of the Seaforth Highlanders, an infantry regiment associated with the northern Highlands of Scotland. During a fierce battle in northwest France, the German Army captured Hardesty while he was manning an aid post on the frontline trenches. For eight months, he was held as a prisoner of war.

Hardesty’s role in a daring escape from the Villingen camp in October 1918 was widely reported in newspapers after he was honorably discharged from the Army. He devised a successful plan to distract guards and short-circuit lighting along a barbed-wire fence so three fellow prisoners could make their way through it. The Germans never discovered his role in the plot. For his heroism, Hardesty received the Victory Medal.

Hardesty was a faculty member at Saint Louis University Medical School from 1920 until his death, and also served as acting chair of its ophthalmology department.

In 1934, he wrote a thesis for membership in the American Ophthalmological Society that proposed a new way to treat glaucoma using systemic medications such as epinephrine. His research represented the first attempt to treat glaucoma in this way. Epinephrine in eye drop form still is used to treat the disease. Hardesty’s work laid the foundation for the development of the oral drug Diamox for glaucoma in the 1950s by Washington University ophthalmology professor Bernard Becker, MD.

Hardesty provided free eye care to residents of the Blind Girls’ Home, Missouri School for the Blind and other schools and orphanages, and to patients throughout the region.

Poole, who was only 14 when her father died, remembers him as a kind and loving man. “I adored him,” she said. “We would walk down to dinner every night on our wide staircase with our arms around one another. He gave me the unconditional love that every child needs.”

“My father was modest and humble,” Poole added. “He wanted to be a doctor simply to help people. On top of his great ability, he gave freely of his time and resources. He stands as a shining example of what every doctor should be.”

Professor saved eyesight of donor’s daughter

In 2012, Jane Hardesty Poole established the John F. Hardesty, MD, Distinguished Professorship in Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, now held by pediatric ophthalmologist R. Lawrence Tychsen, MD. Poole credits Tychsen with saving her daughter Josephine’s eyesight.

R. Lawrence Tychsen, MD, and Jane Hardesty Poole

Born with a developmental disability, Josephine is non-verbal and could not articulate what she was seeing on traditional eye tests. After consulting many doctors near their Manhattan home, Poole read an article in The New York Times highlighting novel ophthalmology treatments at Washington University. In 2004, she and her daughter traveled to St. Louis to meet Tychsen. Through surgery, he restored her vision to 20/40.

The experience convinced Poole that Washington University was the appropriate place to honor her father. “I want to honor him where it’s the best,” she said. — Hilary Davidson

Published in the Autumn 2017 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email