Fifteen years ago, Lilianna “Lila” Solnica-Krezel, PhD, interviewed to lead a new Department of Developmental Biology, a reinvention of the WUSM Department of Pharmacology. She remembers thinking, on her flight home, that she had met 30 leaders and only two were women. But clearly the school was poised for change, and, in 2010, she made history, becoming the school’s first female department head.

In early meetings with the department faculty, Solnica-Krezel sensed how much support and autonomy she would have. “On some issues, we want to be democratic. On others, we want you to listen,” they told her, “but then we would like you to make a decision.” And so she began, engaging everyone in a democratic way, then charting a course. WUSM now has one of the most respected developmental biology departments in the nation.

Just 13 years ago, it was rare for a woman to become a full professor at a medical school, let alone hold an endowed professorship or chair a department. As the Adolphus Busch Professor of Medicine and chair of the Department of Medicine, Victoria J. Fraser, MD, also has done all three. And she has watched the medical school’s total percentage of women faculty grow higher every year.

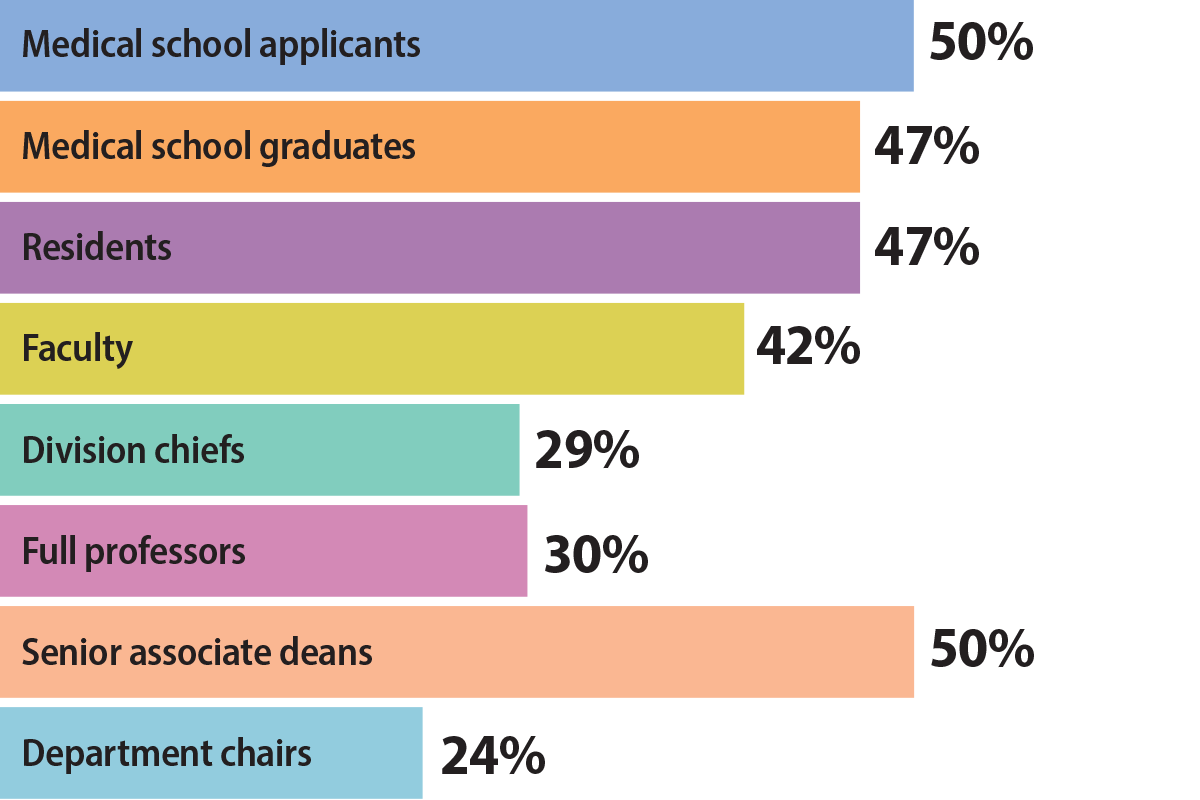

There are still more men holding faculty positions at the School of Medicine — women make up about 42% of the faculty — but that gap has been steadily closing. The share of women faculty rose 31% in four years, from 2016 to 2020. And though there are still only half as many female division chiefs as male, the share of female chiefs rose by 160%.

In 2010, there were 78 women full professors; by 2020, there were 159. In 2010, only 11 women held endowed professorships; by 2022, the number had increased to 61.

“There’s been dramatic change,” Fraser said. “But we must continue to update policies and procedures to ensure equitable recruitment, retention and promotion of women at WUSM.”

In 1995, WUSM’s entering class was 51% female, reaching gender parity for the first time; last year’s entering class had 65 women and 59 men. The same shift has taken place nationwide, but often, for systemic reasons, the number of women in leadership still lags behind.

“When a woman is derailed for any number of reasons, we also may lose women that they would go on to mentor, so it becomes somewhat exponential.”

— Gwendalyn J. Randolph, PhD

Some women have left academic medicine nationally — because of inequities in pay and recognition, harassment, a lack of female role models, or policies too rigid to accommodate family life. Those who stayed sometimes were promoted more slowly. Historically, policies have valued activities more commonly found in male roles and undervalued teaching, mentoring and committee service often disproportionately assigned to women. Pregnancy, childbirth and greater responsibilities related to child care also lead to disparities in grants and publications between women and men.

“When a woman is derailed for any number of reasons, we also may lose women that they would go on to mentor, so it becomes somewhat exponential,” said Gwendalyn J. Randolph, PhD, the Emil R. Unanue Distinguished Professor of Immunology.

Putting heads together

The problems are systemic — and systems can be fixed, points out Dineo Khabele, MD, the Mitchell & Elaine Yanow Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology and the head of that department. “You put in goals, policies, procedures, people who can solve really difficult problems. Then we have common ways of operating that are transparent. And if something is not working, we put our heads together.”

David H. Perlmutter, MD, the George and Carol Bauer Dean of the School of Medicine and executive vice chancellor for medical affairs, intends to make that collaboration easier. He set up a leadership committee on diversity and inclusion, focusing its members on campus climate, hiring and employment culture, curriculum design and delivery, and professional training. Then he recruited Sherree Wilson, PhD, into a new leadership position: associate vice chancellor and associate dean of diversity, equity and inclusion.

Wilson and others are building on years of work. In 2002, Diana L. Gray, MD, professor of obstetrics & gynecology and of radiology, became the associate dean for faculty affairs, charged with increasing diversity and creating an environment in which faculty could thrive. Gray oversaw a gender equity committee (GEC) that broke precedent by advocating to the school’s faculty senate that it pass an amendment allowing the pausing of the tenure clock (a probationary period for early investigator-track faculty lasting between six to 10 years). With this amendment, faculty could request that their clock stop for one year, without negative consequences, to handle personal needs, such as child-raising or elder care.

Gray and the GEC soon learned that only three of the 125 School of Medicine endowed chairs at that time were held by women, so she and a male GEC co-chair set to work.

“We found out which endowed chairs were sitting empty,” Gray recalled. “Then we asked those department chairs, ‘Are you aware that there are only three WUSM endowed chairs held by women?’ Most were not. They were stunned. Sure enough, within 15 months of this awareness campaign, we had gone from three women in endowed chairs to nine.”

Gray also instituted salary equity surveys. Other medical schools were not yet engaged in such work. These surveys, often done with assistance from outside consultants, are time-consuming and costly. The results gave department chairs concrete information about pay inequities that then could be addressed. In 2019, a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlighted WashU as a model, praising its extensive data collection, robust study methodology and diverse task force. Today, school leadership works with departments annually to address outliers in pay.

Now, with the help of Catalyst, an external consulting group, a new Executive Faculty Task Force on Climate and Culture will spend the next months gathering personal experiences and hard data, identifying underlying aspects of the culture that can lead to a negative climate for vulnerable groups. The task force is led by Dineo Khabele, Renée Shellhaas, MD, the David T. Blasingame Professor and associate dean for faculty promotions & career development, and Benjamin Garcia, PhD, head of the Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biophysics and the Raymond H. Wittcoff Distinguished Professor. Meanwhile, faculty leaders continue to scrutinize policies and procedures for anything that might put women at a structural disadvantage. “We now realize,” Fraser said, “some basic things that felt right a while ago”— like limiting awards to early-career stages when women might be pausing their research to start a family — “have unintended consequences that can disadvantage women and faculty with children.”

STEM institutions are honeycombed with individual labs and other small, secluded environments that “may be susceptible to undue influence by individuals in positions of power or authority, particularly as it relates to trainees,” Fraser said. “We need to ensure that all of our clinical, research and educational environments reflect WashU values and promote equity and inclusivity so that everyone can thrive.”

WashU’s new SAFE (Supporting a Fair Environment) reporting system is an important mechanism that provides confidential reporting and robust investigation and feedback, “but we also need to train everyone to speak up and be allies in the moment,” she said.

Networks are there to catch you

Randolph remembers the relief she felt when another woman joined her department at a previous medical school. Both were having kids at the same time, so they shared practical tips, but they also felt an instant understanding with each other.

Today, Randolph is president of the Academic Women’s Network (AWN), an independent body of female faculty at the medical school that promotes gender equity, advocacy and support. Linda Pike, PhD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, cofounded AWN in 1990. She had been the only woman in her department for years.

“It was a restricted existence, because you didn’t have a friend where you could go plunk down in their office and ask for advice,” she recalled. “Male colleagues were concerned about being alone in the room with you. Nobody knew how this was all supposed to work.” In part because of AWN’s advocacy, the medical school created an office of faculty affairs and shined a spotlight on issues of pay equity and need for better child care, family leave and mentorship. The school also brought on an ombuds office.

In 2014, Fraser invited the women residents in the Department of Medicine, along with women faculty, to her home, then asked them what they were experiencing and what they needed. Rakhee Bhayani, MD, professor of medicine and newly appointed vice chair for the advancement of women’s careers in the Department of Medicine, said the younger women’s answers opened her eyes, too. She cofounded and now directs the organization that emerged from that meeting: the Forum for Women in Medicine (FWIM). FWIM provides career development workshops, leadership training and sponsors visiting women professors to share their journeys with women faculty, fellows, residents and students. Nearly always, a career that looked like a smooth ascent had plenty of hurdles.

Networking raises awareness of the subtleties, like “untitling,” added Bhayani. “All the men are addressed as Dr. So-and-so, and the women are introduced by their first name.” Or their ideas are talked over or appropriated at a meeting — until someone deftly inserts, “I like the way you built on Dr. Jenny Smith’s point…”

Expanding the circle

Because she was part time and doing clinical work, not research, Bhayani assumed she would remain at the instructor level. It took advocates who recognized her ability to ultimately get her promoted to full professor.

It also takes advocacy to increase the number of women nominated for prestigious awards, pointed out Renée Shellhaas, a professor of pediatric neurology. “It’s an easy fallback to just say the women aren’t senior enough yet. But if we search for the accomplished, underrepresented individuals, they exist. They just might not be on the shortlist. Sometimes it’s hard to break into that circle.”

Coaching can give women the confidence to set an adequate budget when they write a grant, navigate difficult conversations and speak up for themselves, highlighting their accomplishments. “You can’t just have it on paper,” Gray said. “You have to trumpet it — even if you think that makes you look unfeminine. Because if you can’t be heard or seen, you’re not going to advance. People go into medicine or science thinking their record will speak for itself, and that’s partially true, but those who are the best at promoting themselves get the earliest, highest advancement.”

“Don’t allow others to define you,” advises Solnica-Krezel, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Professor. “Don’t allow others to tell you what’s exciting, what’s important. Make your own decisions.”

That sort of mentoring is an important first step, but what women also need, sometimes even more urgently, is sponsorship. “Sponsors are people who advance your career, and you may not even know they’re doing it,” Fraser said. “They advocate for your skills and accomplishments” — which can mean higher compensation, a promotion, more leadership, more recognition.

Bottom line, Shellhaas said, “We need to be proactive for our junior and midcareer faculty. Are people putting their name in the pool when the right opportunity comes up? Are we having discussions about what the next step in their career will require?” If men are unconsciously drifting toward sponsoring other men, she added, “We need to teach our leaders to recognize that.” And the system needs to acknowledge the time and energy both mentoring and sponsorship require.

“There are many strong, effective leaders at this institution who create safe environments where people thrive,” said Lynn A. Cornelius, MD, professor and division director of dermatology. Unfortunately, there still exist pockets — not many, she added — where leaders put up barriers without even realizing it.

One way to minimize those barriers, Bhayani said, is by “getting buy-in from male allies in key leadership positions. Men are still the majority in leadership roles, and sometimes a man just hears it differently from another man. We have great leaders in our department who have stepped up. They’re willing to be vulnerable and say, ‘I didn’t know this either, but I learned about it, and now that I know, this is how I will handle it.’”

The scales are weighted

Extra support often is necessary, because in the early years of a career, biology still tilts the scales. Rachel Kalbfell, a second-year med student who just finished a term as co-president of the American Medical Women’s Association, brainstorms with her three female roommates: “We have friends getting married and having kids already. When’s going to be the right time for us? I’m thinking of a surgical specialty … .”

She has a mentor who achieved “all of it” really young — career success, marriage, two children. Ironically, she did so by not trying to do everything. “‘Prioritize,’” she told Kalbfell firmly. “‘If you don’t want to cook a four-course dinner every night, sign up for meal deliveries. If you want to be the person who gets the kids ready in the morning, prioritize that.’” Kalbfell chuckled. “She used the word ‘outsourcing.’”

More men are co-parenting and sharing the domestic workload, but “pregnancy, postpartum, breastfeeding — those are big demands,” Fraser pointed out. “WashU has done a lot: building more lactation rooms throughout the campus and expanding resources for child care, sick-child care and elder care.”

When younger women ask Khabele about work-life balance, she answers bluntly: “There is no balance. There is prioritization at different points in your life.”

“Everyone needs to realize it’s a temporary period of your life,” Randolph added, “and helping you get through that is really important.” When a new mother slid a resignation letter onto her desk, Randolph wadded it up. Then they talked things through, and with support, the woman made it through. “Now she is tenured, and she’s loving her lab.”

A changing landscape

Today’s students are aware of the presence of women leaders and have access to their wisdom and experiences. Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, professor of cardiology and vice chair of medicine for clinical research, attended medical school in the ’80s: “All my lecturers were white men, and the deans and department chairs were, too,” she recalled, “and the male attending physicians would be commenting on the female medical students’ attractiveness.”

Randolph remembers comparing her job search to that of male colleagues when her previous department in New York dissolved: “I had more grants, citations and papers than some of these men, but they were getting offers three times better than mine.” She interviewed at several high-profile institutions, she added, where “a woman would close her door and say, ‘You really don’t want to come here.’” One said, “My husband is also a scientist, and when I went up for tenure, they wanted to know if he wrote my grants.”

Later, when Randolph was the one steering a search committee, she heard men say of female candidates, “She smiles too much” or, “She seems like a bitch.” Sweitzer remembers one man pushing for a particular candidate with the words, “He just looks like a chair.”

Today, those words would freeze a room.

“Steps are being taken so that women are valued at this institution, and this will hopefully translate into more empowerment and positions of leadership for younger women.”

— Lynn A. Cornelius, MD

Next steps

In her new position, Shellhaas will further coach leaders to “work against the implicit biases we all carry.” The Office of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion also provides leadership, advocacy, education and training on implicit bias.

Shellhaas is now leading efforts to clarify the process and expectations for promotion across academic tracks and roles — clinicians, educators, research track and investigator/tenure-track faculty.

That means, “if someone has been at their academic rank longer than usual, reaching out to them,” she said. “It could be that they’re very happy and we don’t need to change anything. Or it could be that they are stuck, and we need to figure out why. Do they need different mentors, different skill sets, clarification of expectations? Some people don’t even realize they already meet the criteria for promotion, or they just need one or two more elements to be ready.”

The emphasis on inclusion is making recruitment and retention easier. “Steps are being taken so that women are valued at this institution, and this will hopefully translate into more empowerment and positions of leadership for younger women,” Cornelius said.

Moving more women into leadership will help foster gender equity research, too. More needs to be learned about reproductive health for Black women, Khabele pointed out. And it is probably not a coincidence, Sweitzer said, that only 4.5% of interventional cardiologists are female, and we know far less about cardiovascular diseases that affect women.

“If we want to do our very best for the patients we serve and for the health of the community, we need to tap into the best and brightest talent we have — no matter the gender,” Shellhaas concluded. “We would be crippling ourselves if we didn’t.”

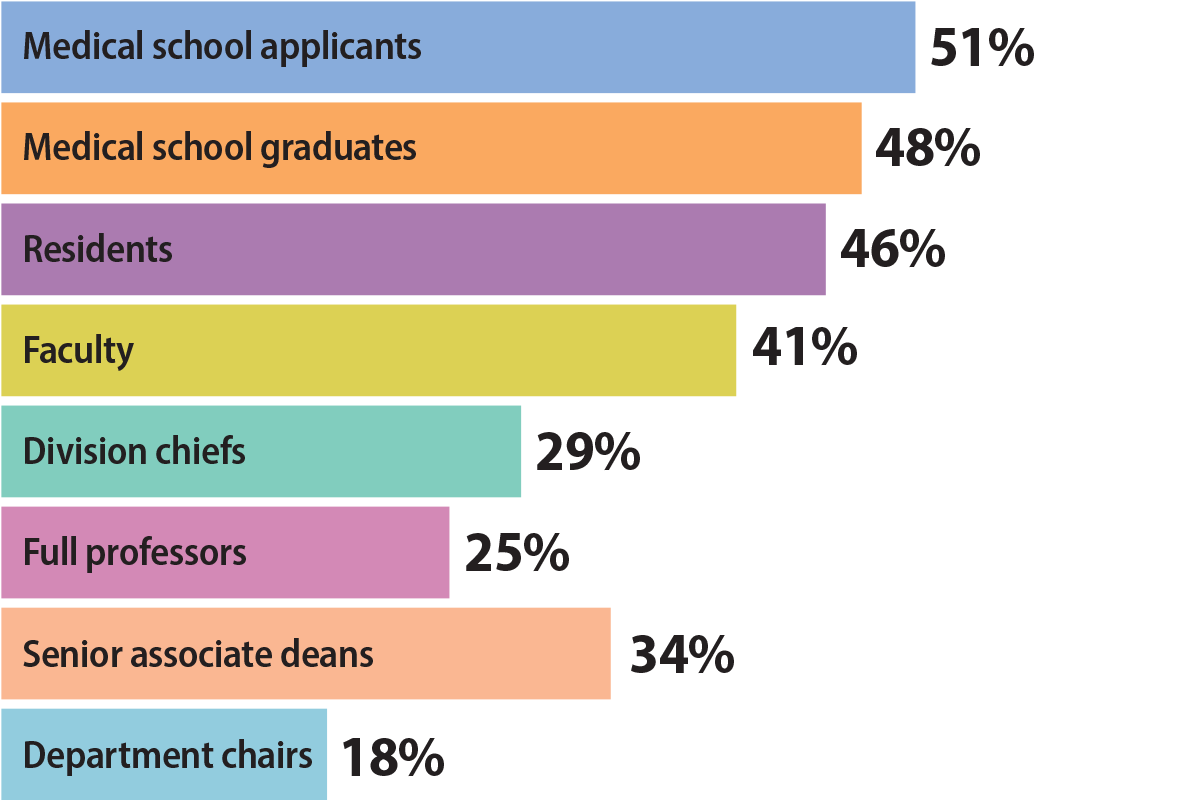

The state of women in academic medicine nationally …

Though women have continued to enter and graduate from medical school in similar proportions to men since 2003, women make up a majority of faculty only at the instructor rank, according to a 2018-19 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Previous editions of this report were released annually, but the AAMC is exploring releasing the report in five-year increments to better illustrate demographic changes.

… and at WashU Medicine

There are still more men holding faculty positions at the School of Medicine — women make up 42% of the faculty — but that gap has been steadily closing. Despite dramatic change, leaders are continuing to scrutinize policies and procedures, looking for any obstacles that might put women at a structural disadvantage.

Published in the Spring 2023 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email