Although an active child, Nancy Hulslander began gaining weight exponentially after kindergarten. By second grade, she was nearing the obese level on the growth chart for girls her age, and encountered teasing.

Nancy was on an all-too-familiar path: Nationally, one in three children is either obese or overweight; obesity rates have more than doubled for children and quadrupled for adolescents in the past 30 years.

Living near the School of Medicine, Nancy had access to evidence-based resources that are unavailable to many kids. She and her mother, Vicki, enrolled in the Comprehensive Maintenance Program to Achieve Sustained Success (COMPASS), a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded study headed by Denise Wilfley, PhD, director of the Weight Management and Eating Disorders Research Program. Four years after completing the study, Nancy is now a 14-year-old freshman and competitive swimmer who maintains a healthy weight.

Early intervention, Wilfley said, is key in stemming the obesity epidemic.

A threat to public health

Although the category “severely obese” (defined as having a body mass index [BMI] at least 20 percent greater than 95 percent of children of the same age and sex) did not exist 40 years ago, it is the fastest growing among young people.

Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, traditionally diseases of adulthood, are being diagnosed in kids with obesity. These children are also at higher risk for low self-esteem, social isolation, depression and anxiety.

“Kids with obesity are more likely to have severe obesity as adults,” said Wilfley, the Scott Rudolph University Professor of Psychiatry. “This generation of youth may be the first to live shorter lives than their parents. And, more of those years will be spent disabled from medical problems. Childhood obesity is a huge public health threat.”

Even though Nancy joined a swim team as a young child, physical activity did not counteract the effects of diet. One of the most misunderstood issues in obesity treatment is the role of physical activity, Wilfley said. Although physical activity has many positive benefits — improved school performance, mood and overall health — it often is an inefficient way to offset calories.

“A child would need to run for three hours to burn off the calories in a fast food meal (cheeseburger, fries and soft drink) that takes 10 minutes to eat,” Wilfley said. “Even very physically active children may gain weight eating a ‘typical’ American diet.”

The kids being followed in COMPASS really are no different than many kids their age who are bombarded daily with unhealthy food options, Wilfley said. And busy parents often have no idea where to start when it comes to regaining control.

More than a “calories-in-calories-out” approach, COMPASS taught parents to re-engineer the home, school and community environments.

The emphasis: Make the healthy choice the easy choice by building social support and routines. Families learned the importance of providing accessible nutrient-dense foods at home; becoming advocates at school; and leveraging the support of friends in healthy eating and activities.

Navigating the way

In collaboration with Seattle Children’s Hospital Research Institute, COMPASS enrolled more than 170 families with one or more children who were overweight and at least one parent who was overweight. The study tested family-inclusive strategies for long-term weight loss in children.

A “traffic light” approach made it fun for kids and simpler to understand. The Traffic Light Diet was designed in the 1970s by Wilfley’s longtime collaborator Leonard H. Epstein, PhD, SUNY Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics, University at Buffalo. The diet uses traffic light colors to categorize food choices: green for anytime foods; yellow for sometimes foods; and red for rare foods.

COMPASS extended the traffic light colors to physical activity. Nancy and other participants were encouraged to eat plenty of green foods (fruits and vegetables) and perform activities like biking. And they were told to limit red foods, which are high in fat and sugar, and sedentary (red) activities such as watching TV.

One of the overarching research objectives was to understand the role of familial and social factors in the prevention and treatment of weight and eating disorders. “Young children do not have power over their environment,” Wilfley said. “If you can change the parent’s behavior and help that adult acquire healthier eating habits and physical activity patterns, that’s going to have a positive effect on the child.”

Getting Nancy’s mom on board provided support at home. But, for new behaviors to stick, modifying other social settings was just as crucial.

The family enlisted the aid of Nancy’s school, which posted the traffic light guidelines. In learning about COMPASS, the school community eagerly teamed up to help Nancy and her peers make healthy choices.

“It’s a double dose of support for the child,” said Dorothy Van Buren, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry. “If a child is trying to eat healthfully, but the only food at a school party is cupcakes, it’s not realistic. This approach helps parents be more aware of what’s happening at school, to speak up and lead by example.”

Using social support is key to solidifying change. Friends also have the power to inspire green eating and activity. “Parents can help by ensuring that playdates involve physical activity and nutritious snacks and by encouraging children to seek out active friends who will make it easier to choose sports over screen time,” Wilfley said. “We want to interrupt that unhealthy cycle to prevent further weight gain and ingrain healthy habits.”

Prior to COMPASS, a nutritionist simply recommended that Nancy add more protein to her diet. “COMPASS helped us realize there is no silver bullet,” Vicki said. “It was important that Nancy and every family member — including our extended school family — commit to making small changes and incorporating them into everyday life.”

As Wilfley has shown, family-based interventions help kids lose weight. Maintaining weight loss, however, remains challenging. Wilfley combined the family-based intervention with a weight-maintenance intervention, and sought to understand the optimal “dose” — frequency and length of treatment — for durable success.

All COMPASS participants underwent four months of intensive treatment, meeting weekly with behavioral change experts and weighing in.

Over eight more months, some families participated in high-dose treatment (32 weekly sessions) with continued focus on enhanced family, peer and community support, which Wilfley terms as social facilitation maintenance (SFM). SFM differs from generally dispensed health advice by recognizing the importance of the child’s social network in bringing about change. High-dose SFM was compared to two low-dose interventions, SFM or an educational control focused on eating and activity behaviors.

Kids who received weekly intervention of high-dose SFM yielded the best weight-loss maintenance outcomes, and children who received low-dose SFM responded better than the control.

Advocating for children

The majority of kids do not have access to such multicomponent weight-reduction therapies. The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommends coverage for both adults and children with obesity. Medicare is providing coverage consistent with these guidelines for adults, but Medicaid and private insurers do not yet reimburse for these treatments in children.

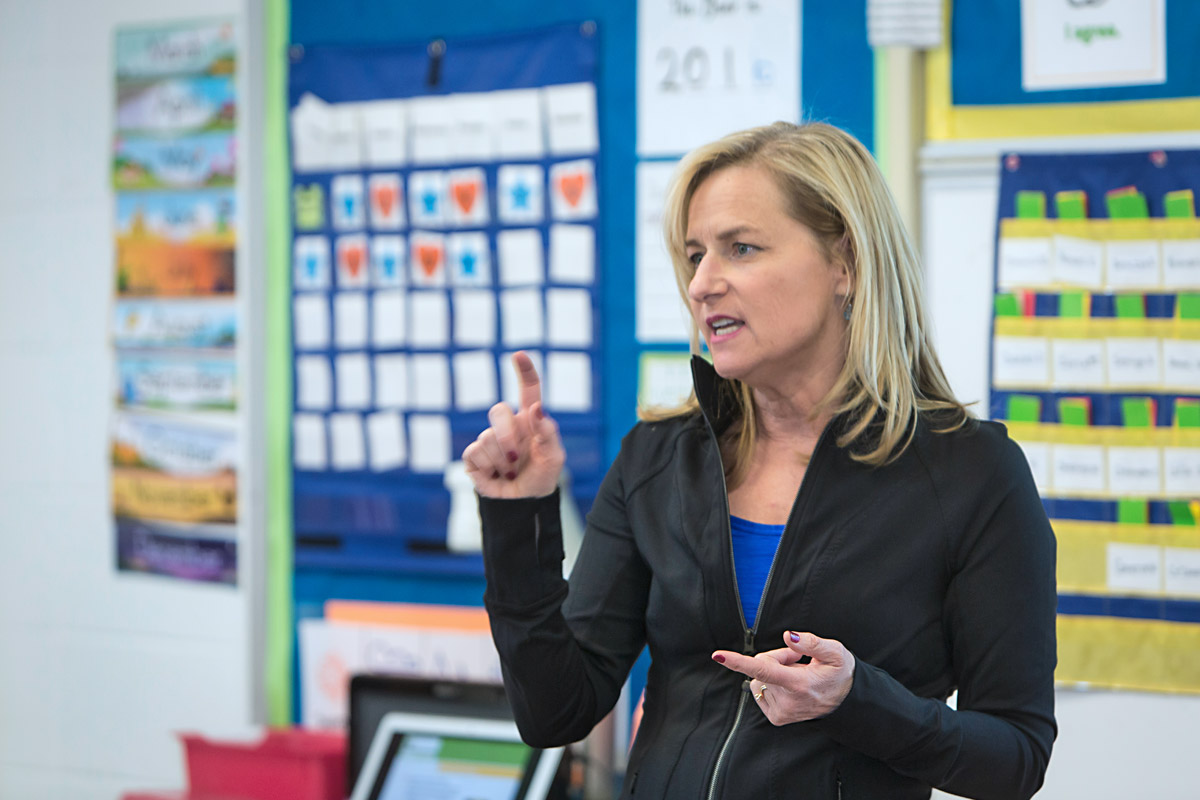

“We have a treatment that works for children with obesity, but several barriers impede its wider spread such as lack of insurance coverage; finding solutions to these barriers fuels my passion,” said Wilfley, who co-chairs the Missouri Children’s Services Commission Subcommittee on Childhood Obesity, which strives to improve access.

Over the past 25 years — with more than $30 million in NIH funding — Wilfley has investigated the causes, prevention and treatment of eating disorders and obesity. Initially Wilfley was drawn to the study of binge eating as a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University. She received NIH support for one of the first controlled studies in those who binge eat by comparing the use of Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), which works to enhance social support and decrease interpersonal stress, to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which aims to improve eating patterns and the way people think about their shape/weight.

Her subsequent studies in documenting the diagnostic and clinical significance of binge eating led to the disorder’s inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a psychiatric diagnosis.

“Denise’s study was groundbreaking,” said W. Stewart Agras, MD, emeritus professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine. “There definitely was no binge-eating disorder at that time and very little treatment. She has clearly shown that IPT is effective in treating binge-eating disorder, and is as good as CBT.”

One of the most striking findings in Wilfley’s study of patients with binge-eating disorder was their report of being overweight or obese as children. This finding sparked Wilfey’s interest in childhood obesity and early intervention.

“Denise is one of the leading childhood obesity investigators working today,” Epstein said, crediting her for innovative treatments that lead to success.

Small changes can reap lifelong results. Wilfley cited the example of an 8-year-old with obesity. At age 8, the child would need to lose only 4 pounds to no longer be obese. That number rises to 16 pounds by age 12, and to 65 pounds by age 18. “Parents may be told not to worry — that their child will grow out of it,” Wilfley said. “But if a child is overweight at age 5, we can predict that he or she will be obese by age 12.”

Wilfley, along with Epstein, is leading a 500-family study focused on implementing weight-reduction therapy in health-care settings. “Moving treatment into primary care capitalizes on the relationship between providers and families and creates a team dedicated to supporting children and families in engineering healthier lifestyles,” Wilfley said. “This study will move us closer to improving accessibility of childhood obesity treatment, and we are working to improve collaboration among insurers, policy makers and health-care providers to make effective care widely available.”

Employee program empowers families

Wilfley recently designed an employer-funded obesity treatment program for St. Louis-based BJC HealthCare. Incorporating insights from COMPASS, the program, named MyWay to Health, is helping employees and their family members lose weight and lower the health-related costs of obesity.

Participating BJC employees and their immediate family members receive private sessions with a wellness coach, who reviews lifestyle habits and develops individualized strategies.

The first group of more than 250 participants averaged a BMI of 37.70 kg/ m2. A year later, results showed an average weight loss of 26.57 pounds and body weight loss of 11.42 percent, as well as significant improvements in cardio-metabolic outcomes, waist circumference, body composition, quality of life and body image.

Stephanie Esses, a pediatric nurse practitioner in the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Pediatric Intensive Care Unit — who did the program with her wife — lost 59 pounds. Their two preschool-aged daughters joined in. “We looked at how we could incorporate our children’s playtime at the park into our exercise routine,” Esses said. “We’ll power walk for an hour before the kids play. It’s a nice lesson in developing a healthy lifestyle for them to see us working out together.”

A 10 percent reduction for someone with a BMI of 39 decreases medical costs by almost $2,600 annually. Based on estimated reduced medical expenses, Wilfley expects MyWay to Health to pay for itself in one year and to produce a return on investment for BJC in subsequent years.

Published in the Summer 2016 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email