IF ON THE WAY TO A MEETING there is a route — direct or winding — through Ellen S. Clark Hope Plaza, past its placid fountain and clusters of lush trees and grasses, Larry J. Shapiro takes it. There co-exist two very different representations of the legacy he leaves Washington University School of Medicine.

When Shapiro took over 12 years ago as dean and executive vice chancellor for medical affairs, the site was home to a parking garage so decrepit that just weeks into his new post, he ordered it shuttered.

Down went the garage, and up went the BJC Institute of Health, a hub for BioMed 21, Washington University’s research initiative to rapidly translate basic research findings into advances in medical treatment. And at the base of the institute’s tower of glass, steel and stone came the plaza, a peaceful respite crowned with a moon-shaped fountain designed by Maya Lin and dedicated to the memory of a woman who fought to protect stem cell research.

This juncture of science and nature and the people who travel through it draw Shapiro in and make him pause. “Always,” said the dean, who announced earlier this year he is stepping down as head of the medical school.

“It’s a reminder of how far we’ve come and how far we will still go. And it’s a reminder that we need to find moments of peace, quiet and appreciation amid the constant motion and discovery.”

The road back

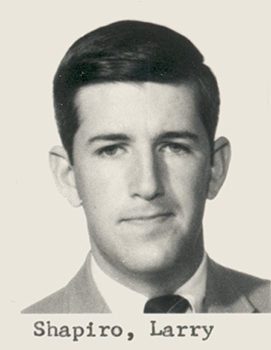

A pediatric geneticist by training, Shapiro first arrived in St. Louis nearly 50 years ago as an undergraduate student in Arts & Sciences at Washington University. A course in developmental biology taught by eventual Nobel laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini and famed embryologist Viktor Hamburger sparked Shapiro’s interest in biomedical science.

“The idea of sequencing a genome would have been total science fiction back then, and the imaging tools we have today that allow us to visualize living cells as they engage in various processes — they had none of that,” Shapiro said. “But they devised experiments that were extremely elegant in their design and that enabled great insights to be drawn, and that captivated me.”

He pursued a medical degree at Washington University, where a class in medical genetics — the school was one of the first to incorporate such a course into its curriculum — decided his career path. He chose pediatrics not only because

he enjoyed caring for children but because the field offered a pathway into medical genetics. Most genetic diseases studied at the time were pediatric in nature.

He completed his residency at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and left the Gateway City to embark on a medical career at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Maryland, the University of California, Los Angeles, and then the University of California, San Francisco.

Three decades passed before he circled back to St. Louis in 2003, this time as a renowned genetics researcher, administrator and pediatrician. He took on the roles of executive vice chancellor for medical affairs and dean.

“Medicine has changed so very much since the days I was in school, but the education my classmates and I received here prepared us to embrace and participate in the changes and not be daunted by the development of new technologies, new drugs, new devices and all of the things that have happened in the subsequent years,” said Shapiro, who is also the Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor. “I appreciate even more today just how wonderful that educational experience was.

“We’ve had a history of extraordinary people with a commitment to excellence, who also have fostered a love of this institution,” he added. “That’s why when I had the opportunity to come back, I knew it was what I should do. Filling these roles has been the greatest privilege of my career. It has reminded me what a remarkable place this is, made so by the amazing, deeply talented people who work, teach and study here.”

Milestones

Shapiro’s time at the helm has seen many of the school’s greatest advances, some of which have served as valuable bridge-builders between the Medical and Danforth campuses.

“He has been very effective in serving as a leader not just for the School of Medicine, but for the entire university,” Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton said. “This is manifest in the development of the Institute for Public Health, a universitywide initiative that addresses complex health issues facing the St. Louis region and beyond. The School of Medicine, and Larry in particular, have played a vital role in its development.

“And he has contributed to the strengthening of biomedical engineering, the Brown School and the Department of Psychology on the Danforth Campus. He has been more than executive vice chancellor and dean. He has had a deep commitment to making Washington University stronger overall.”

Among other such accomplishments that punctuate Shapiro’s tenure was the establishment of BioMed 21, the research initiative of which the dean is most proud. The enterprise, which includes faculty from the university’s Schools of Medicine, Engineering and Arts & Sciences, endeavors to make St. Louis a biotech powerhouse by bringing together basic scientists and clinical researchers from different disciplines to address important questions and rapidly translate findings into

new therapies for patients.

BioMed 21 programs, along with most of the research on the Medical Campus, are funded by the NIH. And under the dean’s watch, the school has ranked fourth among all medical schools in NIH funding, opening the door to breakthroughs in research.

“The first sequencing of a cancer genome in a human occurred in the past decade, and that’s now been expanded to where many thousands of patients have had their normal tissue and cancer tissue sequenced,” Shapiro said. “The school’s ongoing leadership in imaging science, fundamental immunology, translational science and in understanding the root causes of Alzheimer’s — these all have major impact.”

Philip Needleman, PhD, former chair of the medical school’s Department of Pharmacology and an emeritus member of the university’s board of trustees, first met the dean when Shapiro was a medical student. Years later, Shapiro asked Needleman, who had left academia for a long, successful corporate career, to help shape BioMed 21.

“I was away for 20 years, but I was struck when I came back at how much the medical school had invested in cutting-edge technology that supports research — and not just in the flourishing McDonnell Genome Institute, but all of the departments,” Needleman said. “Despite cuts to NIH funding, the medical school has pretty wonderfully survived and continued to grow its research enterprise during the tough times, and that has required a lot of management from the dean’s office.”

Growth arguably has been most noticeable in the Washington University Physicians clinical practice. Last year, it earned $874 million in revenue, and it has enjoyed 8 to 10 percent annual growth in the time Shapiro has been dean. Washington University Orthopedics in Chesterfield opened under Shapiro’s watch, as did, most recently, the St. Louis Children’s Specialty Care Center in west St. Louis County, which is co-owned and operated by the university and Children’s Hospital.

“Larry has strengthened the school’s relationship with BJC leadership and recruited outstanding new department chairs,” said James P. Crane, MD, associate vice chancellor for clinical affairs and CEO of the Faculty Practice Plan. “He has also been a strong advocate for diversity and gender equality at Washington University.”

Shaping new leaders

In his 12 years as dean, Shapiro has hired 18 department heads, all highly respected in their fields and three of them women. Before he took over, no department at the school had been headed by a woman.

Further, when he arrived, three women held endowed professorships. Now, 24 hold this honor. “I’m very pleased with the advances women have made in leadership in other areas of the school, too,” he said.

Overseeing the Department of Medicine, the university’s largest department, is Victoria J. Fraser, MD, the Adolphus Busch Professor of Medicine. Fraser lauds Shapiro for his dedication and thoughtfulness.

“It is obvious to all of us that he cares deeply about the mission of the school,” she said. “He has dedicated his career here to providing outstanding educational programs, building infrastructure, garnering resources for innovative research and fostering exceptional patient care. His warmth, compassion and sense of humor are hallmarks of a leadership style that promotes the collaboration and collegiality the university is so famous for.”

Those same qualities have benefited the university in the ongoing fundraising initiative, Leading Together: The Campaign for Washington University, said David T. Blasingame, executive vice chancellor for Alumni & Development Programs.

“During his tenure, Larry developed a clear vision and an impressive strategic plan for the School of Medicine,” Blasingame said. “His tireless work inspired alumni and friends to invest in every aspect of the school’s mission. Through effective leadership he has helped set the pace for achieving extraordinary success in the campaign.”

Also under Shapiro’s watch, the School of Medicine consistently has remained a top 10 medical school, according to annual rankings by U.S. News & World Report. The magazine’s most recent ranking has the school at No. 6. Further, the school has remained at the top nationwide in student selectivity, a measure of medical student undergraduate grade-point averages and MCAT scores.

Shapiro is quick to credit such accolades to the quality and drive of the students.

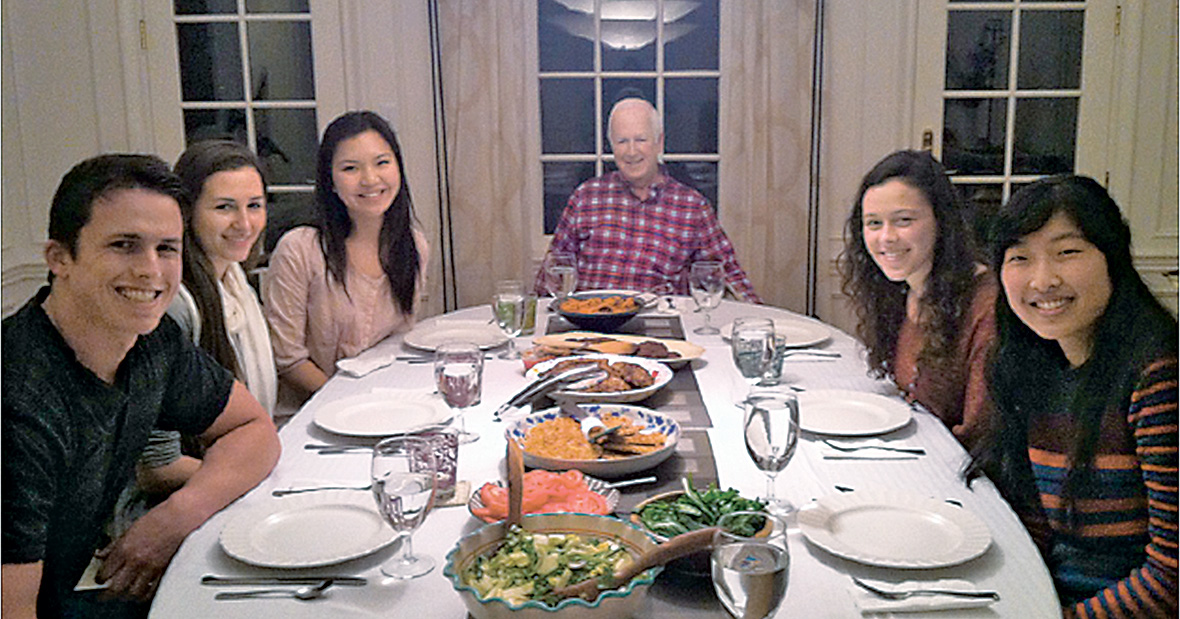

Undecided as to what his role at the university will be when he vacates the dean’s office — perhaps something involving harnessing entrepreneurship, or helping craft health and science policy, he said — Shapiro hopes it will allow him more frequent contact with students. They inspire him every day, he said.

“They’re amazing, and some of them have overcome enormous hurdles in life to get where they are,” Shapiro said. “Every time I start to worry about what the future has to hold, I just walk down the hall and start talking to students, and I think, ‘Everything is going to be OK. If these folks are on the job, we’ll be just fine.’”

Published in the Autumn 2015 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email