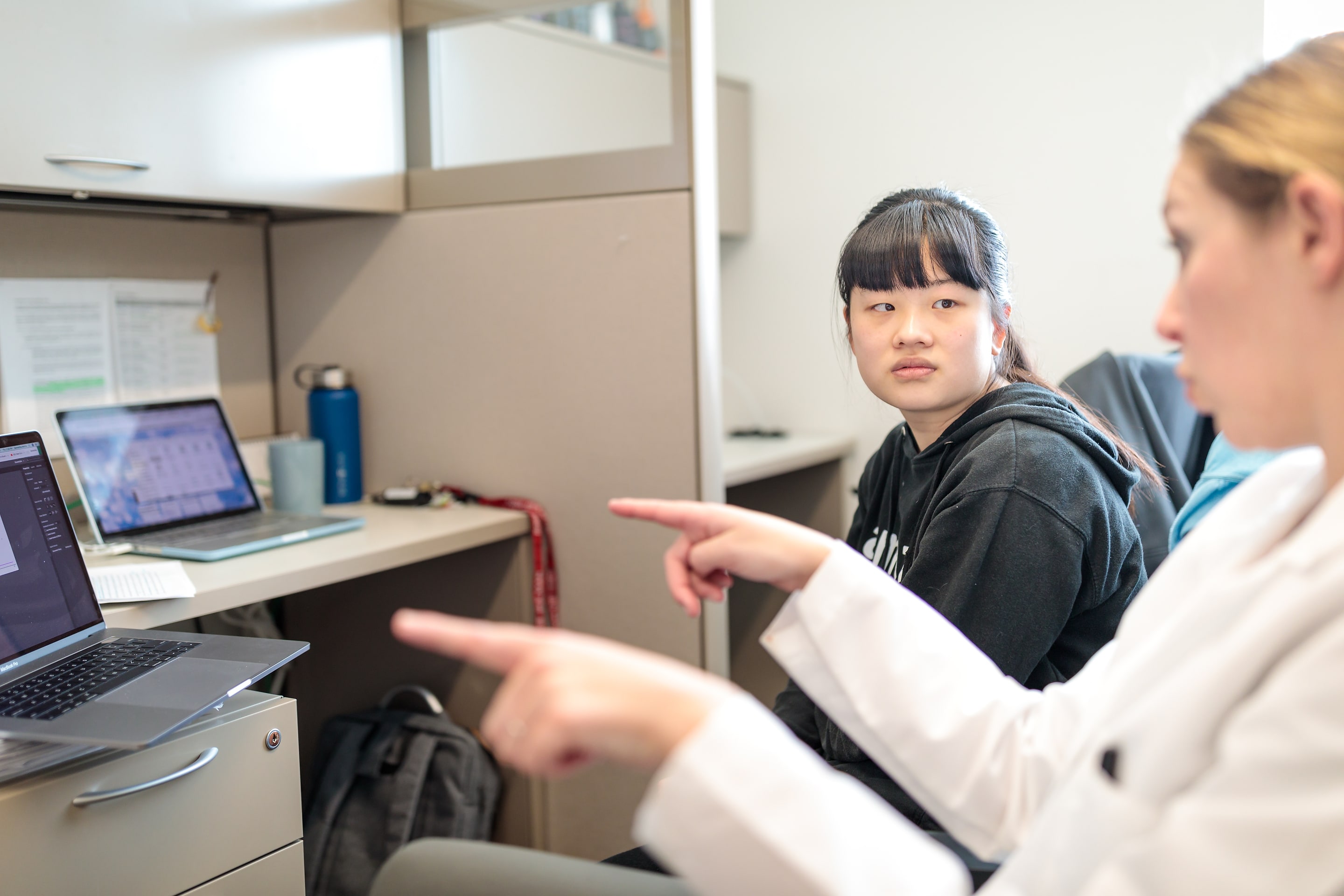

Samantha Morris, PhD, trains MSTP student Chuner Guo to prepare single-cell libraries. “In a new lab, the principal investigator has to get on the bench to do the experiments,” Morris said. “For a while, you are the only person in your lab. Even when people begin to join the lab, you are the only person to train them. Even though the lab is gaining expertise, I still like to do experiments.”

Samantha A. Morris, PhD, an assistant professor of developmental biology and genetics, joined the faculty in 2015. Since launching her lab, she has nurtured a highly collaborative culture involving research techs, students in the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) and the Division of Biology and Biological Sciences (DBBS), and postdoctoral trainees.

For months, the young lab logged many hours, experiencing the ups and downs that go along with discovery and publication. On Dec. 5, 2018, the lab’s first paper was published, in the major scientific journal Nature.

The Morris lab has designed a cellular tracking system that can give scientists a view of how cells develop. This “flight data recorder” for cells could one day help scientists guide cells along the right paths to regenerate tissues or organs.

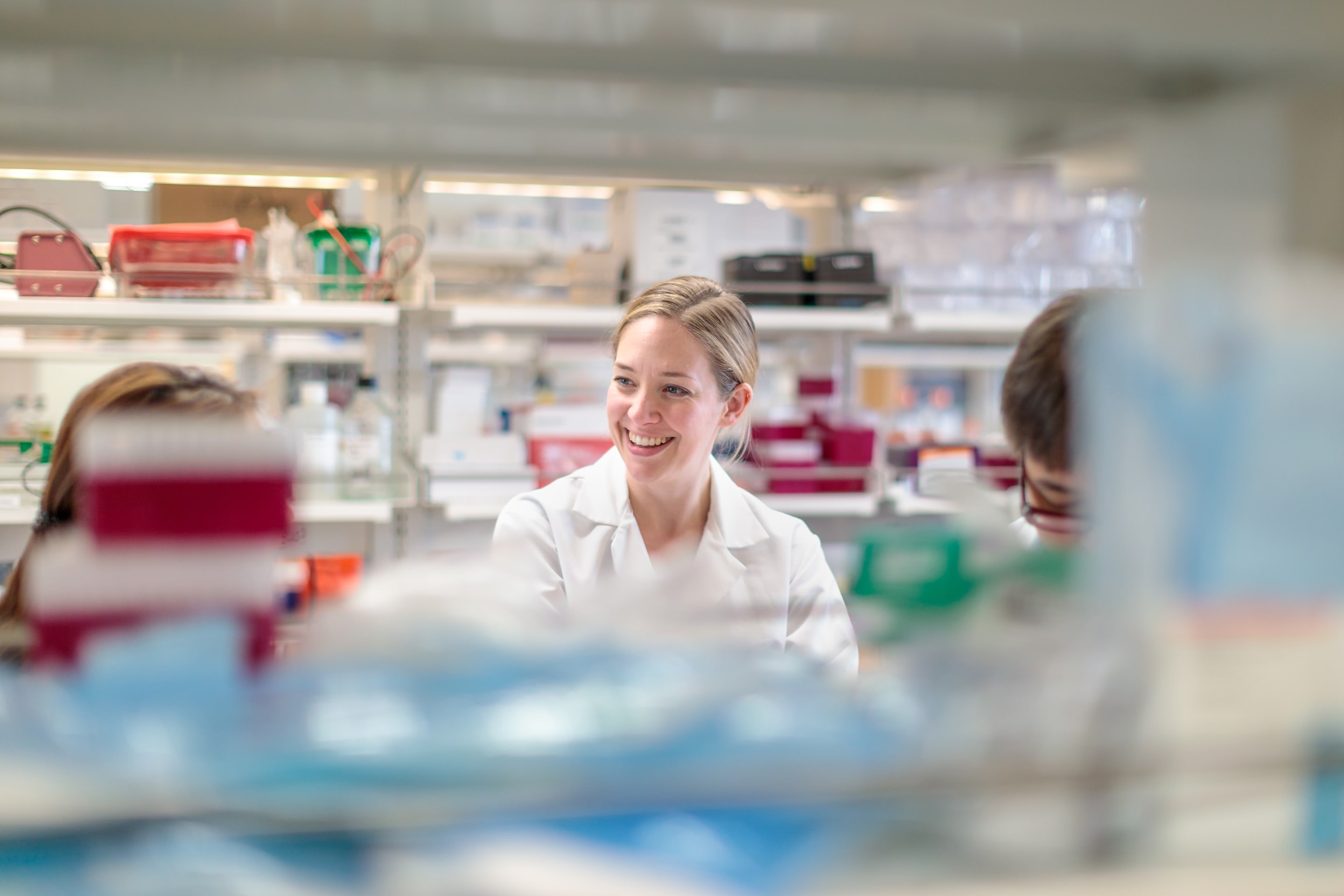

“By doing single-cell experiments, I got to think about science from a technology development perspective,” Guo said, “and I learned a whole lot about how to come up with new ways to better answer biological questions.” DBBS graduate student Xue Yang follows along.

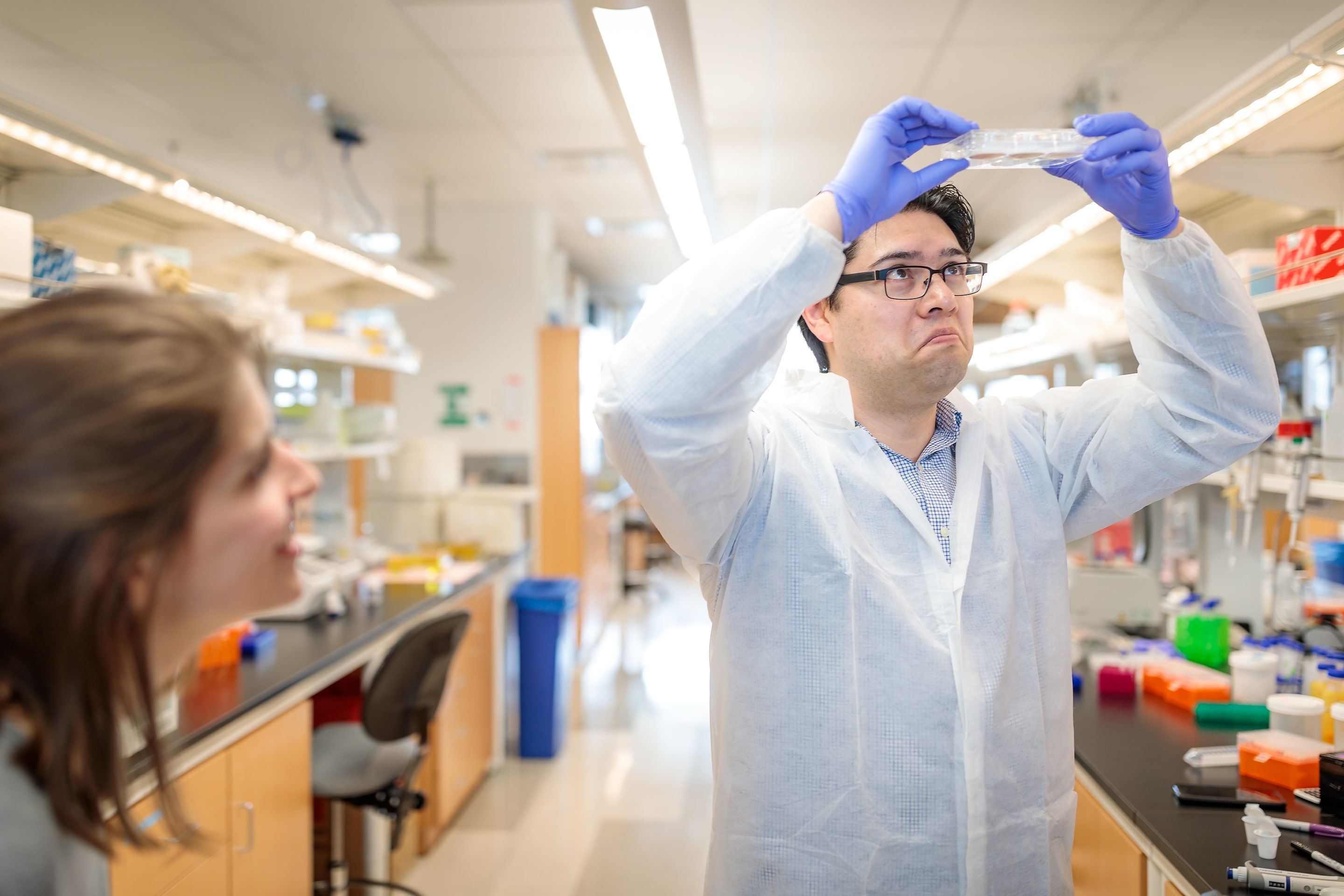

Postdoctoral fellow Guillermo Rivera Gonzalez, PhD, uses half and half to increase the contrast of the stained colonies in the dish. “It’s quite common to use regular household items in our research,” Morris said. “It’s much easier and cheaper to pick up these simple items from the store!”

After staining the cells, Rivera Gonzalez holds them up to the light and likes what he sees: a noticeable difference between the control and the experiment. Research technician Catie Newsom-Stewart leans in to see.

“Almost everyone performs experiments and computational analysis,” Morris said. “These two disciplines feed into each other and that’s where you can get creative. It’s also an extremely collaborative lab, so if someone has a great idea but not all the expertise, they will find help. This leads us in lots of interesting directions because they are fearless in this respect – they have a positive attitude toward failure. I encourage this because if you are not failing, it means you are not asking difficult questions.”

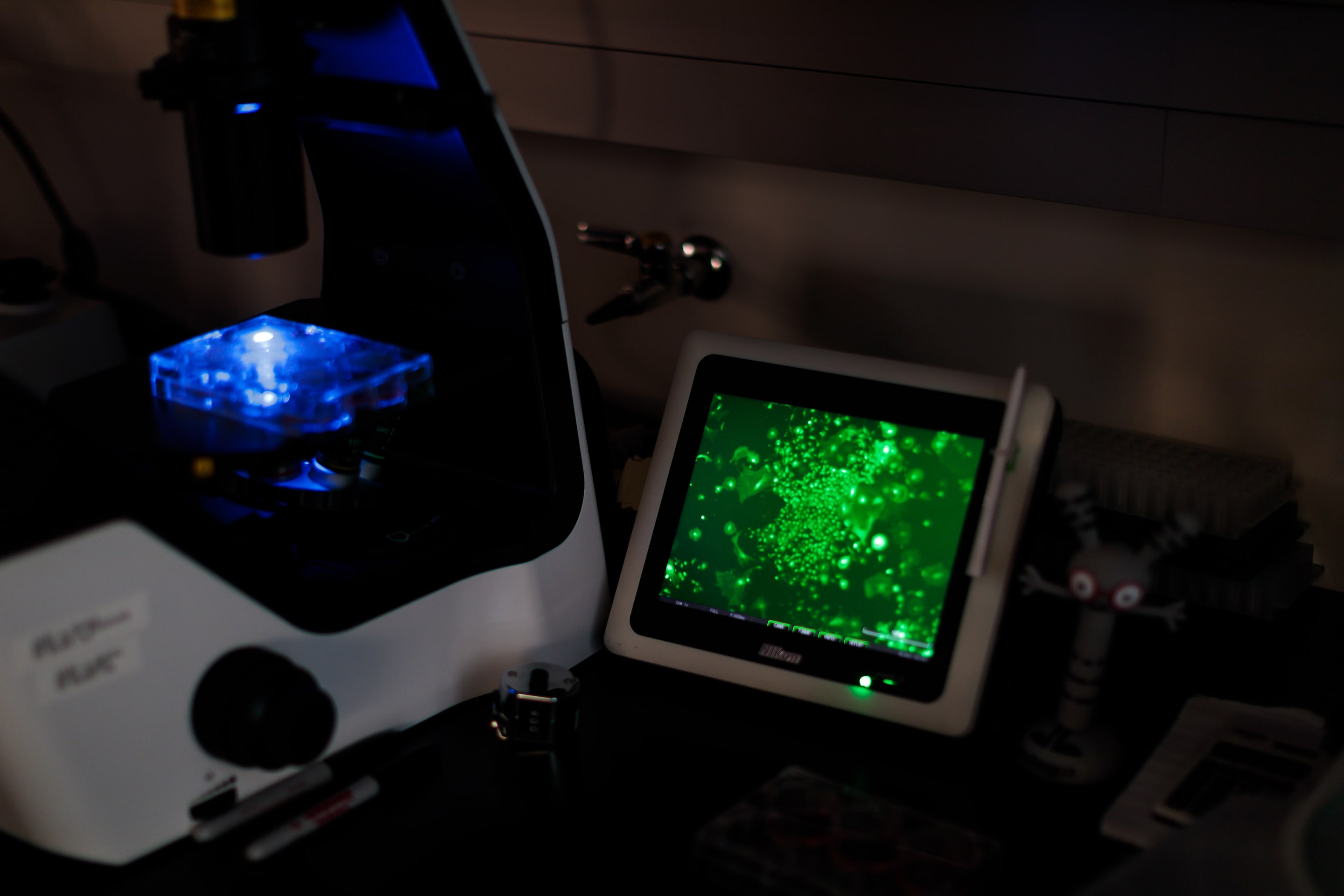

Rivera Gonzalez, PhD, frequently checks on cell growth and changes the media. When Morris saw this image of cell colonies, she knew they were headed in the right direction.

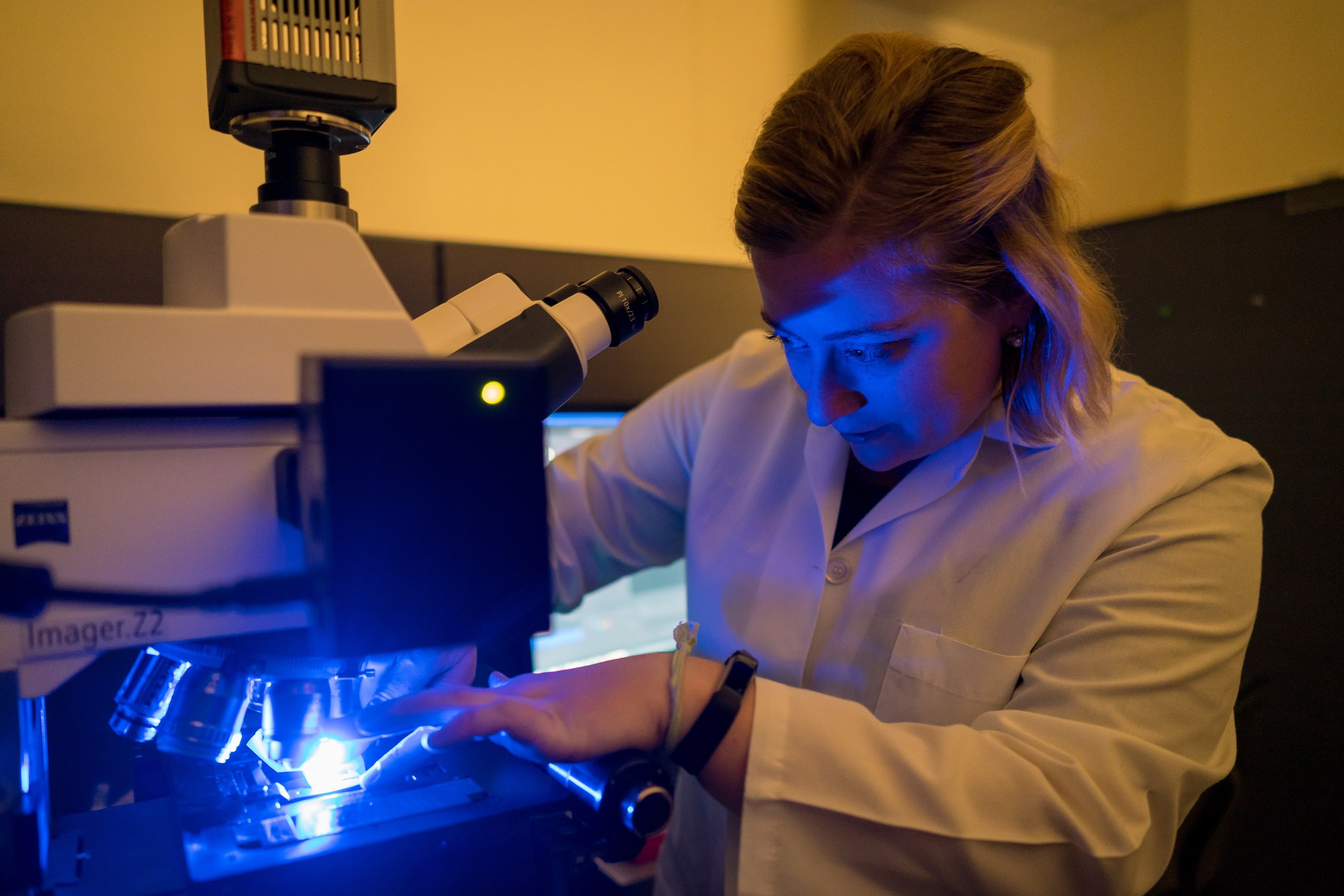

Sarah Waye, a DBBS student, gets images of the cells on a confocal microscope in the Center for Cellular Imaging. “I like doing imaging because the end product can be so beautiful,” she said.

Morris and Waye meet weekly to troubleshoot technical problems. “In talking to trainees, I frequently hear that they feel like they have to pick a field or a track as a grad student and stick with that to be successful. I think that puts a lot of pressure on the decisions they make. You have to work on something you are passionate about now, not something you think you want to work on for the rest of your life. A good PhD should set you up to take on any kind of job that requires critical thinking and troubleshooting, and the trainees should feel supported to explore a range of options.”

Morris discusses different computational methods with DBBS graduate student Wenjun Kong. “I am usually very intimidated by PIs/professors, but Sam is very approachable, and she has encouraged me along the way,” Kong said.

Kong talks with Newsom-Stewart. “Everyone is very friendly, supportive, encouraging and helpful!” Kong said. “I feel like PhD life is very stressful. However, when I’m in the lab, people/friends/lab mates make me happier in some sense. They are more like a large family to me.”

“Most diseases arise because groups of cells no longer function properly, or die,” Morris said. “My lab is trying to understand how we can take easily accessible and plentiful cells, such as cells from the skin, and ‘reprogram’ them to different cell types that have the ability to repair diseased organs. The challenge is that only a few cells reprogram properly, so we develop new technologies to track these rare cells, to understand how they made it to the correct identity.”

Kenji Kamimoto, PhD, left, a postdoctoral fellow, and DBBS graduate student Brent Biddy collaborate in a shared space in the Couch Building. The Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science awarded Kamimoto an Overseas Research Fellowship to work in the U.S. “Kenji is arguably one of the top up-and-coming scientists from Japan,” Biddy said. “As someone from a small rural town in Oklahoma, I would not have met him if it weren’t for science. Science has brought not just Kenji and me closer together but everyone in the lab as well. The ability to freely and enthusiastically discuss our ideas, questions, and passions with one another is not only intellectually rewarding but serves as the foundation for friendships unlike any other.”

Kong troubleshoots people’s computational experiments. The signature red bean bag has become a focal point for discussions and a place to take mental breaks.

The lab’s weekly meetings often are accompanied by food. Although Morris presented on this day, everyone takes a turn.

Newsom-Stewart listens to a presentation during a meeting. “The people in the Morris lab are warm, friendly and love to share their research. They are passionate and creative, excellent at critical thinking, and they’ve really excelled at planning experiments that are both informative and intriguing. I feel that I have gained not only an immense amount of biological knowledge, but also skills in creative and critical thinking, public speaking, writing, experimental planning and networking.”

“There’s not much space to really sit back and relax in the lab,” Morris said. “The bean bag turns out to be a focal point of lab discussions, particularly for troubleshooting. If you are having a tough day and experiments are failing, it is a good spot to complain about it. In this vein, I am also a regular visitor to the bean bag. Perhaps it’s very similar to a therapist’s couch? Whatever it is, it works.”

Morris tells her lab that one of their papers was just accepted as an article in Nature, and Kamimoto celebrates with a high-five.

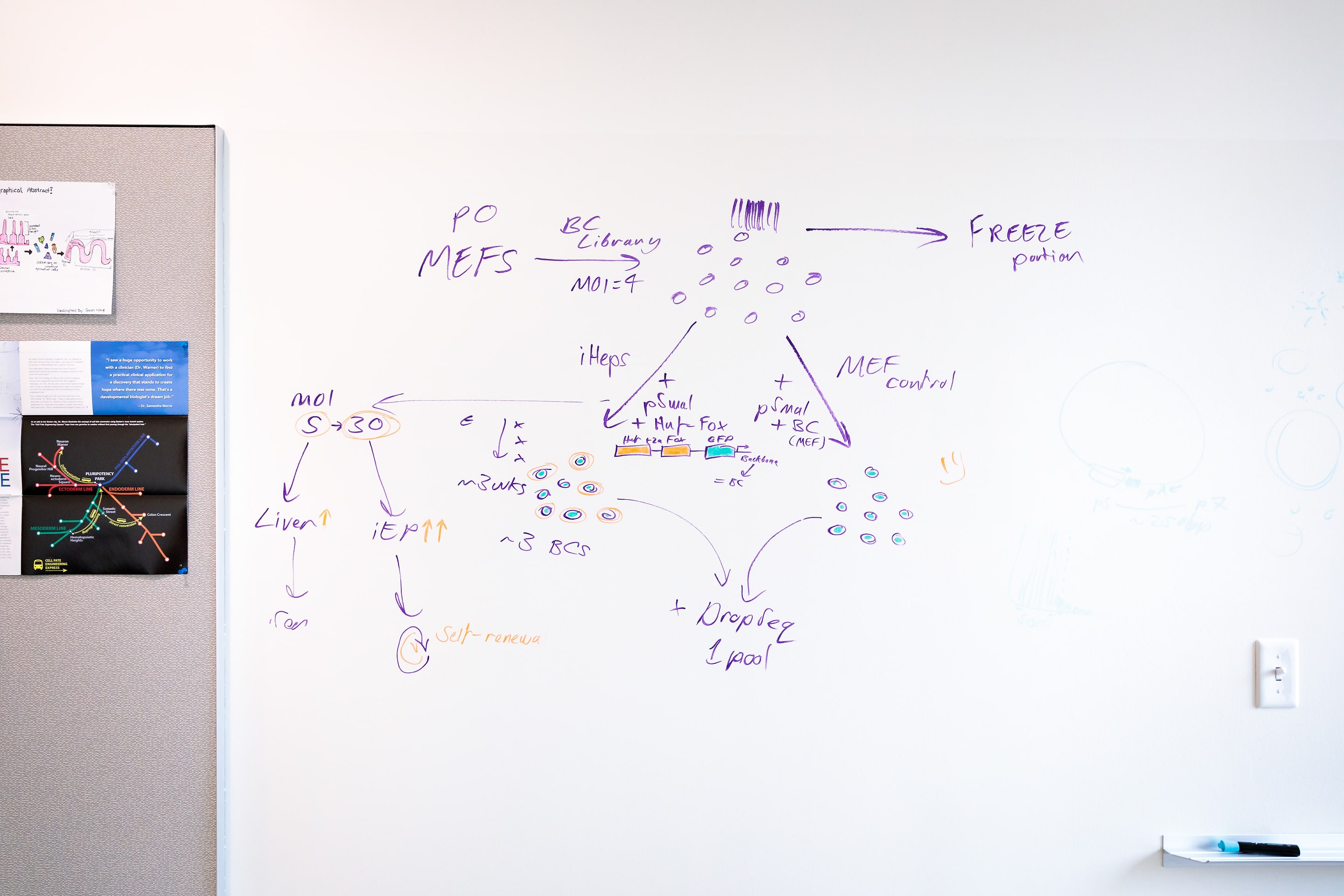

On the wall outside Morris’ office is where the idea for her first paper was born. “It’s become part of the fixtures and fittings now,” she said.

The lab celebrates all major events – grants, paper acceptances, thesis proposals. “One minute I can get an email with good news that we’ve had a grant awarded, then shortly after there can be a disappointing paper rejection,” Morris said. “It’s the amplitude of the ups and downs that surprised me at first. I’ve gradually adapted to absorbing the pieces of bad news by knowing that there’s good news just around the corner.”

After spending 20 years as a photojournalist, Matt Miller became a School of Medicine photographer. “I wanted to apply some of the patience and planning that I’ve used in photojournalism to capturing special moments in a basic science lab,” he said. “The biggest obstacles: finding a suitable lab and my lack of scientific knowledge. Everyone in the Morris lab was so welcoming.” The result: this photo essay.

The research team led by Samantha A. Morris, PhD, was one of 64 teams chosen to compete in STAT Madness, the March Madness of science and medicine.

Published in the Spring 2019 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email