In Africa, Assistant Professor Rupa Patel, MD, MPH, meets with team members from Jhpiego. This non-profit organization works with Kenyan governmental leaders to implement HIV prevention throughout the country.

In 1978, during the infancy of the AIDS epidemic, reports about isolated cases of gay men suffering from a rare lung infection and an aggressive cancer began trickling in to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

That same year, Rupa Patel was born in the Midwest to immigrants from rural Indian villages. While her parents worked long hours in medicine and business, Patel became family mama-bear, a persistent protector helping her non-English speaking, illiterate grandmother as well as her little brother — who never quite fit in — navigate life in white suburban Michigan.

By the time Patel earned a medical degree in 2004, her brother had acknowledged he was gay, and she had discovered a passion for treating people who were emotionally vulnerable, socioeconomically disadvantaged and at risk for contracting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS.

For Patel, MD, MPH, Washington University School of Medicine — with its international reputation for developing HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment therapies — beckoned. She arrived on campus in 2013 as an instructor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases.

“I knew this would be an excellent place for me to make an impact on the community as well as in the medical field,” said Patel, who favors her division’s emphasis on hands-on research and community outreach. “Also, importantly, the HIV/AIDS scientists here are world-renowned.”

Their influential body of work ranges from research on the potent multidrug AIDS “cocktails” developed in the 1980s to ongoing analysis of the relationship between the virus and inflammation to recent studies on the role of gut microbial communities in HIV/AIDS. Such efforts have helped to commute AIDS from a death sentence that, thus far, has claimed 35 million lives globally to a chronic and manageable disease, with treatments that provide a normal life expectancy.

Patel’s mission is to prevent HIV infections altogether. From urban St. Louis to the rural Midwest to remote African and Asian villages, Patel advocates for a once-daily pill called PrEP, which stands for “pre-exposure prophylaxis.” Studies have shown that pre-emptive use of this antiviral drug, when taken consistently, decreases the risk of HIV infection more than 90 percent. In illicit drug users who share needles, PrEP is more than 70 percent effective at reducing risk.

PrEP contains Truvada, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved in 2012 as “an important milestone in our fight against HIV.” The CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) also endorse PrEP.

“PrEP is a game changer for HIV prevention,” said Patel, director of the PrEP Program at the Washington University Infectious Diseases Clinic and a PrEP advisory group member for the WHO.

Rupa Patel, a PrEP advisory group member for the World Health Organization, travels around the globe raising awareness about HIV prevention.

In her various roles, Patel has helped revise international PrEP guidelines and consulted for PrEP programs in places such as Brazil, South Africa and, most recently, India and Kenya. HIV rates in these countries are especially high among teens and young women who work in the sex industry. “PrEP’s public health implications are profound,” Patel said.

The CDC estimates that 1.2 million Americans live with HIV; of those, approximately two-thirds are not in treatment. Yearly, 40,000 people in the U.S. receive an HIV diagnosis, but those numbers have declined about 19 percent since 2005.

However, HIV rates are climbing among certain populations — in men who have sex with men and in African-Americans and other minorities. Reasons include a lack of health-care access, cultural and social stigmas and an overall distrust of the medical profession, a particular problem in the African-American community.

“It is critical to knock down these barriers,” said Patel, noting that the HIV-infected who are untreated or undiagnosed are the most likely to transmit the virus.

Other preventive treatments also are advancing. Patel, along with Rachel Presti, MD, PhD, the HIV director of the school’s AIDS Clinical Trials Unit, and other investigators, are leading a clinical trial testing an injectable drug that prevents HIV and only needs to be given every two months.

“Although AIDS is no longer a death sentence, HIV prevention remains a public health priority,” said William G. Powderly, MD, co-director of the infectious diseases division and one of the reasons Patel wanted to work at the medical school. “HIV/AIDS is not a situation that is going away any time soon. In a short period, Rupa Patel has done a remarkable job establishing PrEP in St. Louis and globally while also conducting influential research,” added Powderly, who also is the J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine and the Larry J. Shapiro Director of the Institute for Public Health. “She has become a leading expert on PrEP.”

Serving at home and abroad

Truvada combines two medications — emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, both used in HIV treatment regimes. For people exposed to HIV, Truvada inhibits virus replication while typically causing minimal side effects.

“It’s a primary prevention strategy like taking aspirin daily to prevent a heart attack,” Patel said.

Since 2014, Patel has led PrEP clinical trials in St. Louis with a focus on raising awareness among primary care physicians and high-risk individuals.

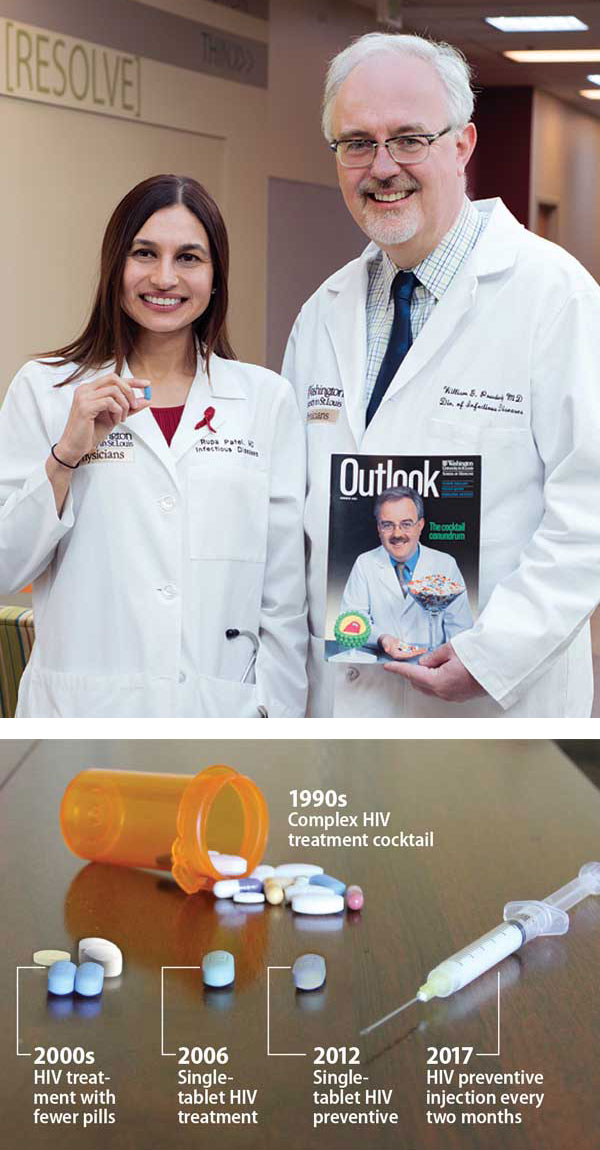

TOP: Bill Powderly, MD, right, holds an Outlook magazine cover from summer 2001 featuring his work with the multidrug “cocktails” then prescribed for patients living with AIDS. Rupa Patel holds the single daily pill called PrEP that now can help prevent HIV infections. Bottom: Therapies for HIV and AIDS have grown increasingly manageable.

The drug — which costs approximately $1,500 for a 30-day supply — is covered through health insurance or financial assistance from the manufacturer.

Patel sees patients in the Washington University PrEP clinic on campus and also monitors patients at a pharmacy-based clinic in a neighboring strip mall. PrEP patients undergo quarterly checkups and receive HIV testing.

“PrEP has been called the gateway to primary care for some at-risk populations. It’s important to seize this opportunity to connect this group with other prevention services,” Patel said.

Despite published research acknowledging PrEP’s effectiveness, the drug is not widely prescribed. One-third of primary care physicians and nurses don’t know it exists, a 2015 CDC report found. PrEP programs are at various stages of implementation in the U.S., Canada and Australia, as well as clusters of countries across the globe.

At an international HIV research conference in 2016, Patel presented an analysis on missed opportunities for PrEP. Based on surveys of 102 patients in St. Louis, her research found two-thirds had asked their primary care physicians for PrEP but were not prescribed it. The physicians cited discomfort with discussing the medication, in part, because they knew little about it.

“Many physicians see PrEP as unnecessary because they believe their patients can just use a condom to prevent HIV,” Patel said. “But condoms are not 100 percent effective. The best scenario is to use both a condom and PrEP because, together, the likelihood of contracting HIV is miniscule.”

More people at high risk for HIV would take PrEP if they understood it better, said Matt Swango, 39, a social worker at Saint Louis Effort for AIDS who works with Patel on PrEP outreach. “Many people say PrEP has taken the fear out of sex so they are able to get on with their lives,” he said. “It’s incredible if you compare it to the 1980s when people were literally dying in the streets. Younger people may not realize how far we’ve come because they’ve always lived in a world with AIDS.”

Critics cite concerns such as PrEP’s lack of protection against sexually transmitted diseases as well as its dependence on people remembering to take a pill every day. There also is fear that PrEP will increase sexual promiscuity; however, studies have shown otherwise.

“One of PrEP’s biggest obstacles is a major reluctance to talk about sexual practices and sexual health in our society,” Patel said. “Men who are having sex with men may feel uncomfortable talking to a physician while physicians do not always view it as their role to discuss sexual health. Some never ask about a patient’s sexual preferences. This is a missed opportunity to identify a person who may be at risk for HIV.”

Talking frankly about sex

Patel never misses an opportunity to discuss PrEP, said Dave Rueschhoff, 35, one of Patel’s patients who takes PrEP as “an additional layer of security regarding HIV prevention.”

Rueschhoff, who helps Patel with PrEP outreach and serves as a member of the community advisory board for the PrEP injection study, said Patel has a special talent for connecting with others. “She is caring and genuinely respects all individuals,” he said. “Dr. Patel knows her patients’ culture and asks about their lives. She uses LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer) language to assess risky sexual behaviors. She is not judgmental about anything people tell her and that makes them feel comfortable opening up to her. Talking explicitly about sex does not faze her.”

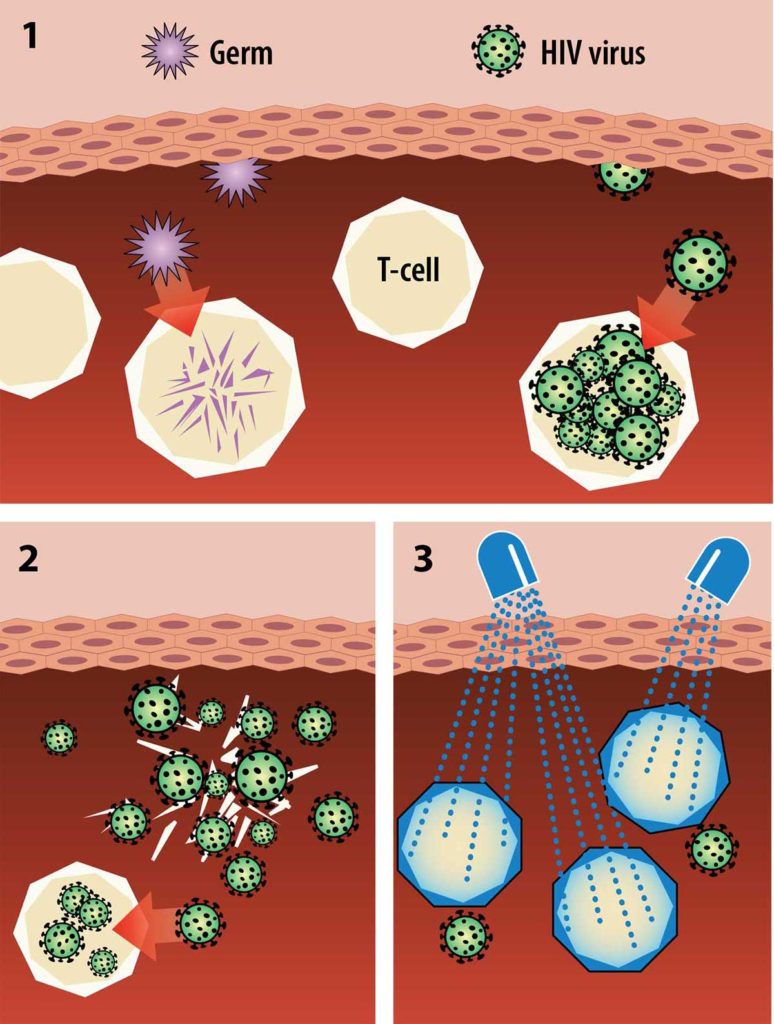

Preventing HIV infection:

1. The body can fight off and destroy most germs (purple) before they replicate, but HIV (green) infects immune cells called T cells. 2. HIV uses reverse transcriptase to rapidly copy itself inside the T cell. The T cell bursts, causing the virus to spread. 3. PrEP is a combination of two medications called emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, which are nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. These two medications block the virus from entering the body’s immune cells and, thus, prevent HIV infection.

Indeed. Patel distributes PrEP flyers everywhere she can, visits LGBTQ nightclubs and bathhouses to educate owners about PrEP, advertises on social media and coordinates community outreach through events and LGBTQ phone apps.

A craving for ice cream recently led Patel to Boardwalk Waffles & Ice-Cream, a new eatery in a trendy, LGBTQ-friendly St. Louis neighborhood.

“Can I hang a PrEP information poster here?” Patel asked co-owner Keith Cotton.

Patel chatted with Cotton about business, everyday life and PrEP. “I want you to know about PrEP in case customers see the poster and ask about it,” Patel said, eating an ice cream waffle.

Patients and colleagues agree that Patel’s blunt, yet empathetic, approach is a key strength in helping patients. It’s one she learned before graduating from medical school. In 1999, her 17-year-old brother came out as gay. “I went to LGBTQ dance clubs with him and immersed myself into his world to gain insight into what he was going through,” Patel said.

“My experience with my brother showed me how to approach communities at risk for HIV, de-medicalize or de-stigmatize sexual health, and create a clinic environment that offers more support and comfort for individuals.

“Washington University continues to be at the forefront of ending HIV because its physicians combine compassion with outstanding research.”

![]()

Over the past 30 years, David B. Clifford, MD, left, and Lee Ratner, MD, PhD, have conducted groundbreaking research on HIV, AIDS and related treatments.

Moving science forward

Researchers propel AIDS from death sentence to chronic disease

As the mysterious AIDS epidemic gripped the world in the 1980s, scientists at the School of Medicine went to work, contributing to groundbreaking research on HIV, as well as treatments such as the highly active antiretroviral therapy, commonly known as the AIDS drug cocktails.

In 1985, Lee Ratner, MD, PhD, the first to sequence HIV while at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), joined the School of Medicine and helped to steer HIV/AIDS research to prominence.

More than three decades later, Ratner, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Professor of Oncology, is internationally renown for his research on HIV and AIDS-related cancers and has been involved in dozens of clinical trials affiliated with the NIH’s AIDS Malignancy Consortium.

In 1987, Washington University expanded its research opportunities by establishing the AIDS Clinical Trials Unit (ACTU), part of a prestigious national network known collectively as the AIDS Clinical Trials Group and funded by the NIH.

“Since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, Washington University has been a significant, productive contributor to HIV/AIDS research and treatment therapies,” said David B. Clifford, MD, ACTU director and the Melba and Forest Seay Professor of Clinical Neuropharmacology in Neurology. “Research here and worldwide is leading toward a cure for AIDS. Not long ago, I would have thought it improbable. But the science is moving forward.”

At Washington University’s ACTU, approximately 20 studies are underway examining all aspects of the disease. Clifford is leading research on whether statins reduce heart attacks and strokes in HIV patients, who are more likely to develop heart disease than people without the virus. “The study is looking at starting the drugs earlier than in the general population for our HIV patients in an effort to reduce these complications,” Clifford said.

Former ACTU Director William G. Powderly, MD, was a key researcher in evaluating the AIDS cocktail drugs, a concoction that decreased viral levels so patients could live longer. More recently, his research has focused on understanding long-term side effects of HIV medications, particularly metabolic problems such as diabetes, lipid abnormalities and osteoporosis.

“From a scientific perspective, it is incredible that over the past 30 years, the AIDS epidemic went from a deadly disease to a preventable, manageable and chronic disease,” Powderly said.

Published in the Spring 2017 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email