The French philosopher René Descartes believed that body and mind are separate and independent, each capable of existing without the other. Modern neuroscientists would argue the opposite: The mind is what the brain does, they say, just as pumping blood is what the heart does. WashU Medicine neuroscientists are pushing the boundaries of our understanding, investigating how the cells, circuits and structures of the brain give rise to the complex mental functions that make us who we are.

The mind-body connection

Neurologist Nico U. Dosenbach, MD, PhD, believes he has proven Descartes wrong. Dosenbach led a study showing that brain areas controlling movement are plugged into networks involved in thinking, planning and control of involuntary functions such as blood pressure. The findings represent a literal linkage of body and mind in the very structure of the brain. “What the brain is for is successfully achieving your goals without hurting or killing yourself,” Dosenbach said. “You can’t do that if the thinking and planning part of you isn’t connected to the moving and feeling part of you.”

Do you really want to know?

In the information age, we’re surrounded by knowledge. When should we seek it out? And when is it better not to know? According to research by neuroscientist Ilya E. Monosov, PhD, your brain has specific neural circuits that measure how uncertain you are about whether to seek knowledge. Different circuits are involved when weighing whether to seek information about good possibilities versus bad. “Our curiosity to know the future is altered in many mental disorders, particularly OCD, anxiety and depression,” Monosov said. “Understanding how the brain handles uncertainty could lead to new approaches to mental disorders associated with an inability to tolerate uncertainty.”

You sure about that?

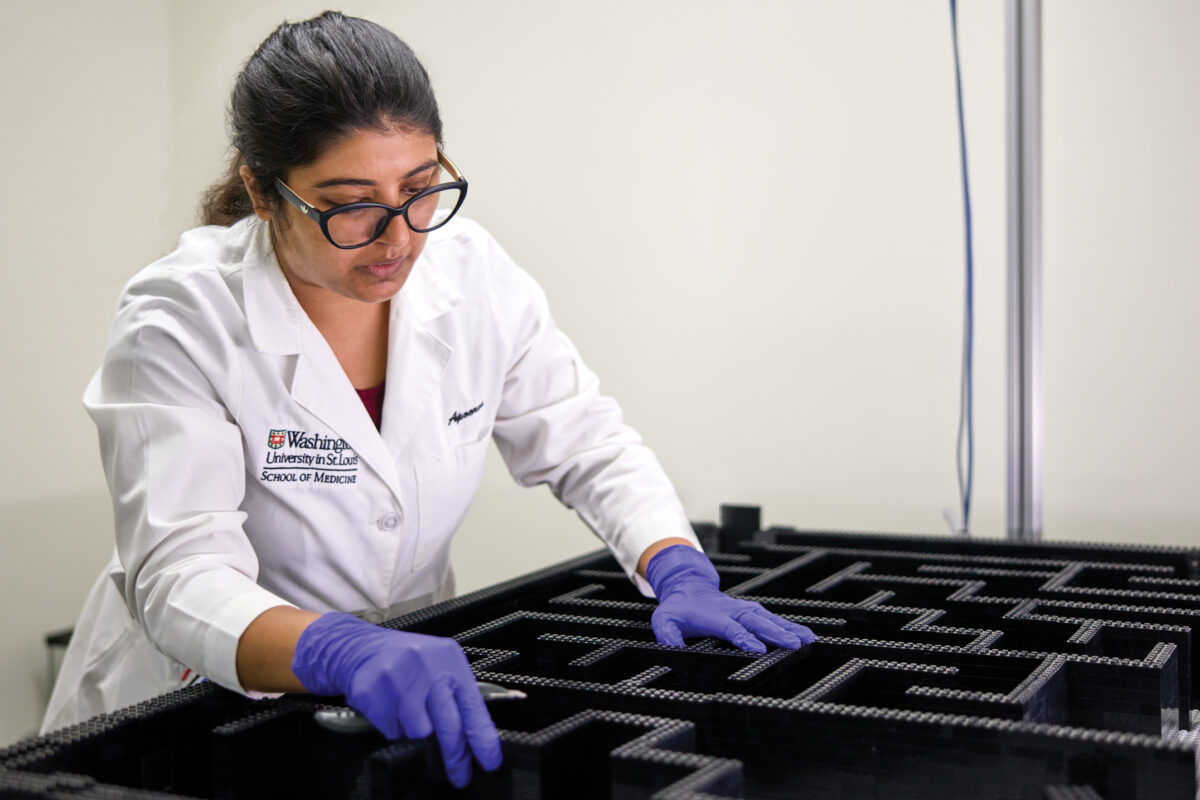

Have you ever waited in a slow-moving line and wondered if it’s worth the wait? In moments like these, our “confidence neurons” are silently assessing our commitment. Neuroscientist Adam Kepecs, PhD, took this idea into the lab, training rats to identify ambiguous sounds and giving them the choice to skip uncertain trials. When faced with challenging decisions, rats often chose to opt out, reflecting their confidence level. Kepecs identified unique neurons that tracked a rat’s moment-to-moment confidence and guided its persistence in waiting. By devising quantitative methods to study subjective mental states in animals, his research offers new insights into human disorders rooted in misjudged confidence, such as hallucinations and anxiety.

Make your choice

When you are faced with a choice — say, whether to have ice cream or cake — specific sets of brain cells fire as you weigh your options, one set for each option. Since he discovered those cells in the mid-2000s, neuroscientist Camillo Padoa-Schioppa, PhD, has been carefully figuring out the rules that determine exactly how they encode subjective value and interact to determine a final choice.

“In a number of mental disorders, such as addiction and eating disorders, patients consistently make poor choices. We’re trying to understand why.”

— Camillo Padoa-Schioppa, PhD

Navigate the neurosciences

Continue exploring the extensive scope of neuroscience research conducted at WashU Medicine.

Published in the Winter 2023-24 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email