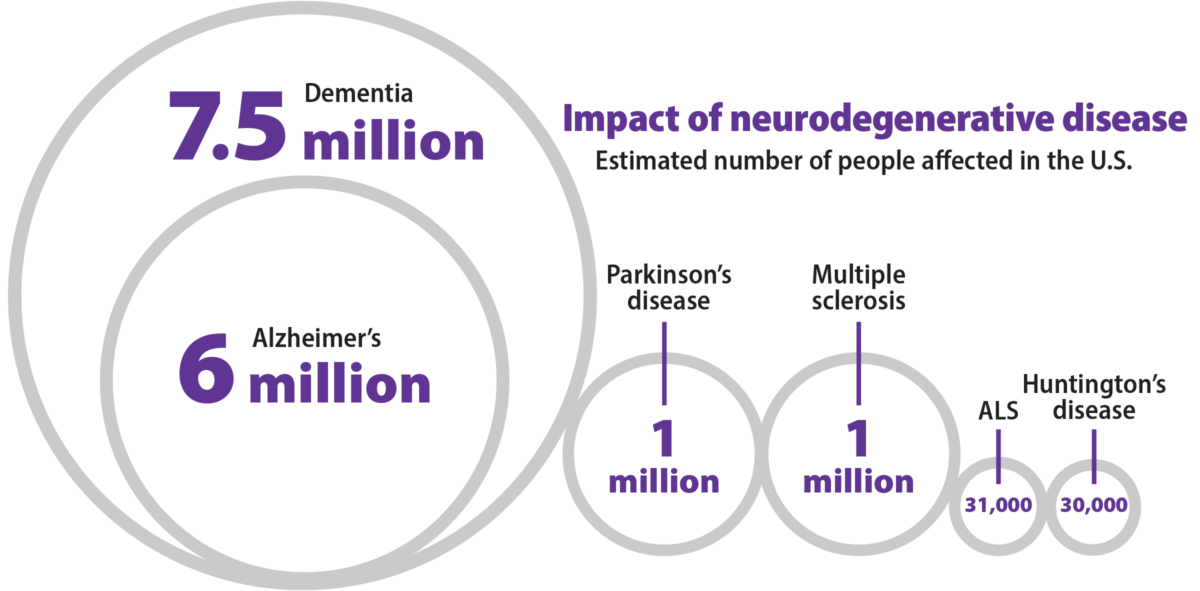

Neurodegeneration tends to start slowly, almost imperceptibly. For a variety of reasons, neurons gradually stop functioning as well as they used to, and some start dying. In Alzheimer’s disease, the most common neurodegenerative disease, signs of decay are detectable long before memory problems arise. This slow start provides an opportunity to intervene while the problem is still manageable. WashU Medicine researchers are working on detecting and healing ailing neurons, opening up paths to new treatments.

Gut feeling

Gut bacteria may play a surprisingly important role in Alzheimer’s disease, according to two groundbreaking papers this year. Studying mice, neurologist David M. Holtzman, MD, and microbiome expert Jeffrey I. Gordon, MD, discovered that gut bacteria influence the activity of immune cells that can damage brain tissue. Meanwhile, neurologist Beau M. Ances, MD, PhD, and microbiome expert Gautam Dantas, PhD, reported that the microbiomes of healthy people and people with presymptomatic Alzheimer’s differ in significant ways. Taken together, the studies suggest that the gut microbiome might harbor important clues to how Alzheimer’s develops, which could lead to new therapeutic approaches.

Frayed nerves

Nerve damage, whether caused by illness or injury, involves deterioration of the axons, the part of neurons that transmits signals and serves as the wiring of the nervous system. Geneticist Jeffrey D. Milbrandt, MD, PhD, and developmental biologist Aaron DiAntonio, MD, PhD, identified a key molecular driver of axonal injury and figured out how to inhibit it. They founded the startup Disarm Therapeutics — since acquired by Eli Lilly and Co.— to develop drugs to help the millions of people living with debilitating nerve damage by blocking or slowing axonal degeneration.

Therapy for few; hope for many

In April, the FDA approved the drug tofersen — based on research by WashU Medicine neurologist Timothy M. Miller, MD, PhD — for an inherited form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a paralyzing neurological disease. The drug targets a gene called SOD1, and clinical trials show that it slows disease progression in the 2% of ALS patients with SOD1 mutations. The drug’s success provides new hope for disease-changing therapies for other forms of ALS, once thought to be untreatable.

“My whole career has been built on the assumption that ALS is a treatable disorder.”

— Timothy M. Miller, MD, PhD

Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

When the FDA approved the first disease-modifying Alzheimer’s drug, lecanemab, earlier this year, it changed the game. Only people with mild or very mild symptoms are eligible for the drug, making early diagnosis critical. Neurologist Randall J. Bateman, MD, whose previous research led to the development of an Alzheimer’s blood test, recently discovered a biomarker with the potential to pinpoint the stage of disease and track progression. A clinical test based on this biomarker may help people gain access to next-generation therapeutics.

Why symptoms appear with age

Huntington’s disease is caused by a genetic error present at birth, though symptoms such as memory lapses and clumsiness don’t arise until middle age. Developmental biologist Andrew S. Yoo, PhD, pioneered a technique to transform skin cells from Huntington’s patients into neurons that carry each patient’s genetic defect. This allowed him to study Huntingon’s noninvasively. To better understand aging in Huntington’s patients, he obtained skin cells from patients of different ages. He discovered that as patients age, a vital cellular process called autophagy gradually becomes impaired in such neurons, causing them to deteriorate and die, and that boosting autophagy improves neurons’ survival.

Ensuring research benefits all

Led by director John C. Morris, MD, the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center has become a national leader in health equity with one of the most diverse volunteer cohorts in the country. WashU Medicine researchers have uncovered troubling racial disparities: some Alzheimer’s blood tests yield results that differ by race; and African Americans tend to encounter delays in obtaining specialist memory care, putting them at risk of missing the drug treatment eligibility window.

New tricks for old drugs

People diagnosed with neurodegenerative diseases typically have few treatment options. To expand the formulary, some scientists are looking at repurposing drugs already approved by the FDA for other ailments. Using human genomic data, geneticist Carlos Cruchaga, PhD, identified 15 existing drugs with therapeutic potential for Alzheimer’s, as well as seven for Parkinson’s, six for stroke and one for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In related work, neurologist David M. Holtzman, MD, discovered that some white blood cells exacerbate brain degeneration. “It’s likely that some drugs that act on white blood cells called T cells could be moved into clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease relatively quickly,” Holtzman said.

Navigate the neurosciences

Continue exploring the extensive scope of neuroscience research conducted at WashU Medicine.

Published in the Winter 2023-24 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email